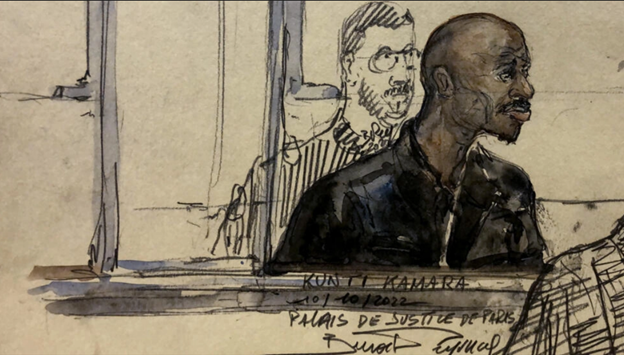

Kunti Kamara in 2022, with police, in the protective glass box in which he sits through the trials

PARIS, France – Lawyers defending Liberian warlord, Kunti Kamara, in his appeal of his 2022 conviction for war crimes, advanced their second challenge to the case in court Friday, arguing that France’s statute of limitations for such crimes is ten years meaning Kamara should not have been charged in 2018 with the crimes that took place in 1993.

Prosecutors and lawyers for the civil parties in the case argued that the ten-year time period does not apply because it is preposterous to suggest that victims would have been able to come forward with their complaints to Liberian law enforcement in the ten years after 1993 when Liberia was still mired in civil war. Even since then, they said, it would be impossible to have a Liberian prosecuted inside the country for war crimes. They point to evidence provided by Luther J. Sumo, the Lofa county prosecutor, earlier in the trial, that it was only in the last two years that the county even had a second prosecutor with a law degree.

Kamara is seeking to overturn his conviction and 30-year prison sentence handed down by a jury in November 2022. This is the second challenge Marilyn Secci, Kamara’s lead defense lawyer, has put forward in this hearing. She also put forward an argument that Kamara was only 15 when the crimes took place and said, therefore, the case should be heard in the juvenile justice system and not the adult one. Secci told the court that Kamara was born in 1978 and not 1974 as he told immigration officials when he sought asylum in the Netherlands in 2001. If he was born in 1974 he would have been 19 in 1993. Kamara told this court he did not know the year he was born. Esah Kouyateh, Kamara’s older brother, appeared early in the trial saying definitively that he remembered Kamara was born in Karnplay, Nimba County, in 1978.

Kamara with his defense lawyers in 2022

Noone has disputed the idea that Kamara was under 18 when he joined Ulimo as a refugee in Guinea when it was formed in 1991. The defense argues he was just 13. Prosecutors say he was 17. None of the victims has been clear on Kamara’s age at the time Ulimo terrorized Lofa County in 1993 and 1994 after it took control of the county from the rebels of Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front for Liberia. Witnesses have not given strong opinions on whether he was 15 or 19 when they encountered him in 1993. But they have made clear that he was in a leadership role. The jury may find it hard to believe he would have commanded so much respect and fear at just 15 years of age.

Secci pointed to many inconsistencies in witness’s memories of what happened 30 years ago as evidence that they are not reliable.

“Why will this court want to accept the voices of the witnesses who have given us inconsistent testimonies that they don’t remember when they were born, but will not want to accept that of the accused?” Secci asked. “Many people attested to the fact that Kamara was a minor, and other witnesses told this court that they knew Kamara as a child soldier.”

Sabrina Delattre, lawyer for the civil parties, and Myriam Fillaud, lead prosecutor, questioned Kamara’s claim this late in the process. They told the court that throughout the six years since Kamara was arrested and processed through the French criminal justice system he had never changed his date of birth nor told authorities or investigators that he made a mistake in his date of birth. When Kamara was examined by psychologists and investigators he consistently gave the same date of birth.

“Mr. Kamara’s affirmation of his age that he was born in 1974 was constant in every declaration throughout the six years,” Fillaud said. “It is only during this argument of the appeal he is saying that he doesn’t know when he was born. It’s a fact that Kamara was above 18 years old when he partook in the war in Liberia.”

The defense also told the court that Kamara should be heard under Liberia’s judicial system, where the crimes were committed, and not the French system. They pointed to Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommendation that the country set up a specialized tribunal to prosecute perpetrators of the wars. This argument may find some sympathy among the all white French jury. Many here, including Alieu Kosiah, Kamara’s former Ulimo ally convicted of war crimes in Switzerland, have citizen the fact that an all-white French jury should sit in judgement of a Liberian from a civil conflict they cannot understand.

Prosecutors countered that it would have been impossible for the victims to receive justice in Liberia. In the 21 years since Liberia’s civil war ended every president has blocked the establishment of a war crimes court until the ascension to the presidency this year by Joseph Boakai. A bill to establish the court passed the lower house of the Legislature this month but is facing hurdles in the senate where some of those most likely to be prosecuted, including Prince Johnson, hold seats.

Kumara has admitted to being a commander with Ulimo in Lofa County in 1993, but he denies he committed the 11 counts for which he was convicted including murdering a sick woman, torturing a schoolteacher and eating his heart, and the gang rape of a nine-year-old girl.

Throughout his ongoing appeal hearing, Kamara has called the witnesses who testified against him, including the international justice organization, Civitas Maximas, and its Liberia partner, the Global Justice and Research Project a “group of liars and conspirators,” whom he said have plotted to have him other former Liberian warlords prosecuted in the United States, France, and Switzerland.

Next week presiding judge, Jean-Marc Lavergne, two judges and nine jurors will reach a verdict in the case. In the French system a majority of jurors need to find the evidence of guilt to be sufficient under the “innermost belief” to uphold the original conviction.

The trial continues next week…

This story was a collaboration with FrontPage Africa as part of the West Africa Justice Reporting Project.