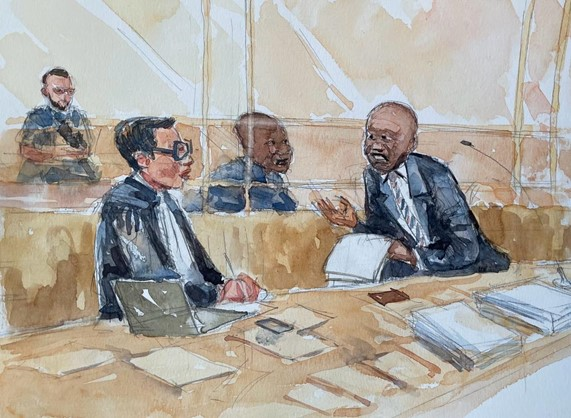

Kamara in a protective glass box talks to his lawyers. Credit: Leslie Lumeh/New Narratives

PARIS, France – The 4,400 miles between France and Liberia closed on Friday when present day news from Liberia made it into the appeal hearing here of convicted war criminal Kunti Kamara. Court President (chief judge) Jean Marc Lavergne used the testimony of Alain Werner, director of the Switzerland-based justice advocates Civitas Maxima, to ask about this week’s passage of a bill to establish a war and economics crimes court through the Liberian legislature.

Werner updated the court on the passage of the bill through the lower house and the plans for a court. He underscored why, he said, he believes a court in Liberia is essential for justice. Werner quoted Alieu Kosiah, the former Ulimo commander, who Werner helped convict for war time atrocities, in a Swiss court in 2021.

“Kosiah has always said that that it is an injustice that he is being pursued but no one is pursuing the big people,” Werner told the court. “He is right. It is the smaller ones that are being pursued.”

That is why, Werner said, a Liberian court to try the “most notorious perpetrators” listed in the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report, is essential. But he hoped that the 16 cases that have been pursued against perpetrators in Liberia’s civil war – including two Europeans – will be instrumental in prosecutions of faction leaders in a war crimes court.

President Lavergne asked Werner, as he had asked TRC Commissioner John Stewart during his appearance this week, whether the news of the international trials in Europe and American were known to Liberians.

Werner, like Stewart, assured the court that Liberians had been actively engaged in news from the trials. He pointed to New Narratives’ journalists in the courtroom and told the jury that Liberians were receiving news in newspapers, radio and online from the trials. Stewart had credited the coverage of the trials with driving support for the war crimes court among the Liberian population. Stewart and another witness, Liberian police investigator Patrick Massaly, made a point of thanking the jury and the French court for pursuing justice on behalf of victims.

Werner was also asked to respond to accusations from Kosiah, Kamara, and others targeted in international prosecutions including Agnes Taylor and Gibril Massaquoi that he and Hassan Bility, head of Civitas Maxima’s Liberian Partner Global Justice and Research Project, had offered witnesses bribes and made promises of resettlement in other countries.

Werner told the court the accusations were refuted by the witnesses themselves. Dozens have traveled to testify in trials in Europe and America and the only one to have claimed asylum was Kosiah’s own defense witness. Werner assured the court that the witnesses, including those who will come to testify against Kamara in this trial want nothing but justice.

“They didn’t come for money,” Werner told the court. “They didn’t come for asylum as some people claimed. They didn’t come for any other thing. They came because they had a simple conviction that they needed justice to be done.”

The defense motion claiming that Kamara was 15, and therefore too young to be tried in an adult court under French law, is still hanging over the court. Until now Kamara has claimed that he was born in 1974 and was therefore 19 when the crimes, for which he was convicted, took place in Lofa in 1993. At the start of the trial the defense called Kamara’s brother to testify that Kamara was born four years later, in 1978. President Lavergne has decided the court will rule on that issue at the end of the trial. Questions about his age will come up in relevant testimonies over the next three weeks of the trial.

The court will rule on another key issue early next week. The defense has filed a motion that the statute of limitations for torture is 10 years in French law, far shorter than the 25-year period between when the crimes were committed in 1993 and Kunti’s indictment in 2018. Prosecutors have argued that the judicial system in Lofa barely existed before 2018 and thus it was impossible for victims to bring a case against Kamara there. If the court rules in Kamara’s favor almost all the 11 counts could be thrown out.

Later in the day Général Jean-Philippe Reiland, one of the French police investigators who went to Liberia to investigate the crimes, went through the 11 charges against Kamara and recounted the interviews and reenactments that he did with victims and witnesses in Lofa County. He detailed harrowing details of accounts he heard of crimes committed by Kamara – rape, murder, torture, cannibalism and forced labor that will be heard by the jury from the victims themselves, starting next week.

Reiland said all the witnesses clearly stated that “CO Kunti” had committed the crimes or directed rebels to commit them.

He also detailed phone calls that were intercepted between Kamara and members of the Mandingo community in France. Phone recordings read before the court had Kamara saying that he was aware that investigators in the Netherlands were pursuing him. He said he destroyed his passport and traveled to France where he sought help from Liberians in France to flee France for Guinea.

Reiland who had investigated cases in Rwanda previously, was asked to compare Rwanda and Liberia. He emphasized the extreme poverty he encountered in Liberia.

“Rwanda, compared to Liberia, is like Switzerland,” he said.

In Rwanda, Reiland said, police investigators had investigative and technical capacity and equipment to take photos, record interviews etc. They were able to map GPS coordinates for locations for example and submit them directly to the court in France. Liberians did not have technical capacity and faced challenges with electricity, equipment, and internet access.

The roads were a challenge. Reiland took 14 hours to drive to Lofa on terrible roads. Language differences were a challenge, and it was impossible for French investigators to ask direct questions. Everything had to go through Liberians. Medical exams were not available.

Reiland rejected the defense claim that photos had not been presented to witnesses. He said everyone in Liberia had been shown photos. Only one was able to recognize Kamara. He put that down to the great length of time since the people had last seen him when he was a teenager.

He also said he didn’t believe that they had coordinated responses. He said they all appeared spontaneous and authentic.

Defense lawyer Marilyn Secci continued to try to sew doubt in the minds of the jury. She challenged numerous aspects of the investigation. Had the investigators seen a birth certificate, she asked? How could they know this was the same Kunti Kamara that victims blamed for the crimes? Reiland responded with a clear answer to each question, but it will be up to the jury to decide if the state has presented its case to the burden required in criminal cases, “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The trial continues on Monday.

This story was a collaboration with FrontPage Africa as part of the West Africa Justice Reporting Project.