MONROVIA, Liberia — On a rainy August evening three days before a national referendum, white United Nations tanks rolled down Tubman Boulevard, the Liberian capital’s main road, and took up positions in front of the president’s house and the national legislature. It was a signal Liberia’s security forces and the U.N. force feared poll violence.

Liberia’s Oct. 11 general and legislative elections are seen as a barometer of the nation’s security, one term into President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s administration and eight years since the end of a brutal civil conflict that persisted over two decades and took more than 250,000 lives.

The vote will also determine whether the U.N. will maintain its peacekeeping force in the small West African nation, according to Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, chair of the Liberia U.N. Peacebuilding Commission.

“The U.N. is on target to leave quite soon,” he said.

The mandate for the approximately 10,000 U.N. personnel stationed in Liberia was set to expire Sept. 30. Whether to renew it for another year will be voted on in the coming week. U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, in his latest report to the U.N. Security Council, recommended extending the mandate of the U.N. Mission in Liberia (UNMIL).

“I’m really afraid in this environment. When the elephant fights, the grass will suffer.” – Dan Saryee, the Liberia Democratic Institute

“There needs to be a very well-calibrated withdrawal, nothing precipitous,” said Al Hussein. “Within the Security Council, Liberia is a weak state but it’s no longer in the emergency ward — it’s sort of graduated from the ICU.”

The U.S. has trained more than 4,000 police officers since the restructuring of the department in 2004, but officers’ pay is low, leaving them susceptible to corruption, according to the U.S. State Department’s 2010 human rights report on Liberia. Some say Liberia relies too heavily on UNMIL soldiers and is not prepared to manage serious conflict.

“Peace is fragile,” said Liberian Senator Prince Johnson, the ex-warlord responsible for the torture and killing of President Samuel Doe in 1990 and who is running for president.

“We have less than a 2,000-man army and when you have a country emerging from war, where you have 85 percent unemployment, that country risks going back to conflict,” he said. A source at Liberia’s justice ministry who requested anonymity out of fear he would be made a target said he does not trust Liberian security forces to quell trouble during elections.

“All indications are pointing to the fact that there will be violence. Look around you. The state has to depend on UNMIL for security because the state does not have enough security to get things under control when violence breaks out,” he said.

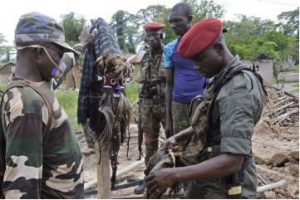

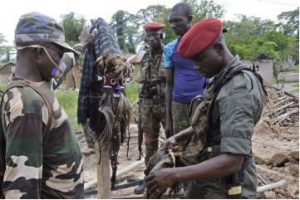

The most serious threats to security are “the persistence of mercenary activities and arms proliferation,” according to a report on Liberia by the International Crisis Group that was released in August.

“The post-election crisis in Ivory Coast from December 2010 to April 2011 has tragically revealed the extent of the problem for the entire region,” said the report. “Hundreds of young Liberian fighters were easily recruited for a minimum of $500.” Ban also voiced concern about the slow implementation of recommendations by Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“Other areas of concern include continuing ethnic and communal tensions, disputes over land and other resources, drug trafficking, and limited employment and livelihood opportunities,” said a U.N. statement.

Major recent busts, including the $100 million cocaine deal thwarted by Liberia’s drug enforcement agency last year, illustrate the growing prevalence of drugs trafficked through Liberia from South America en route to Europe, according to a June report by the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime.

“The traffic is increasing, and it has a chance to continue increasing, because as in other parts of Africa there is minimal governance and the law enforcement capacity is non-existent. Now the U.S. is trying to establish a serious-crimes unit there,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, a drug-trade expert with the Washington, D.C.-based Brookings Institution.

Presidential and legislative elections scheduled for Oct. 11 are only the second since Liberia emerged from the decades-long crisis that devastated the economy. U.N. special representative in Liberia Ellen Margrethe Loej said recently the referendum and presidential polls “will be a litmus test for Liberia’s progress towards peace and democracy.”

Dan Saryee of the Liberia Democratic Institute describes the security situation as “worrisome.”

“People are doing all sorts of things to disrupt this process. I’m really afraid in this environment. When the elephant fights, the grass will suffer,” said Saryee.

Liberia’s Senate committee on security has said it would do all it could to ensure safe elections. “We are working closely with the Ministry of Justice and the Liberian National Police to beef up security in the country to ensure a violence-free election,” said Maryland County Senator John Ballout.

U.S. Ambassador Linda Thomas Greenfield called on political party leaders to rein in their supporters, warning Liberia could easily mirror the conflict in Ivory Coast that originated over last November’s disputed presidential elections.

There are still about 172,000 Ivorian refugees in Liberia according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ latest count. The neighboring governments recently signed a pact that will repatriate hundreds of Ivorians who were arrested along the border with arms and ammunition.

In recent weeks Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf has given two speeches on security around the elections, warning that political violence could easily devolve into civil conflict.

“Violence against, and intimidation of, political actors and individuals undermine and destroy democracy,” said Johnson Sirleaf in a nationwide address. “Such conduct is the beginning of anarchy, and if not deterred, such conduct could reverse the political gains we have made and probably cause our country to retrogress into another civil conflict.”