“The boy is my neighbor’s son,” says the grandmother. “We eat and play together. They came to me begging I agreed not to go to court. That court thing can waste time and money. I just want my little girl to be all right.” – A grandmother to rape victim.

“The boy is my neighbor’s son,” says the grandmother. “We eat and play together. They came to me begging I agreed not to go to court. That court thing can waste time and money. I just want my little girl to be all right.” – A grandmother to rape victim.

Published in FrontPage Africa on February 5, 2013. See original piece here.

By New Narratives fellow, Tecee Boley

Monrovia Decontee, 14, sits with her father in a small examination room at the Duport Road Sexual Gender Based Violence Clinic. Tears roll down the cheeks of both father and daughter as the head nurse Elizabeth Kekula presses her palm to the girl’s back and holds the father’s hand.

Decontee aborted her first child because she was raped by her next door neighbor’s son. The father puts his hands over knees in an effort to stop trembling of anger. The father recounts the story of the rape because his daughter can’t stop crying. He says the perpetrator threatened his daughter.

“He told her he was going to kill her if she told anyone,” he says. “So she kept the torn-up clothes. He is my next-door neighbor’s son who is above 20 year-old.”

As unlikely as it may seem Decontee is lucky. At least she is still alive. Another 14-year-old rape victim Olivia Zinnah was buried on Dec. 22 after suffering years of pain and surgeries following a rape by her own uncle when she was just 7.

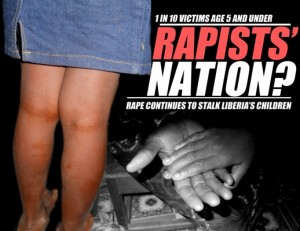

These 14 year-olds are just two of many Liberian girls who lose their lives, will not be able to get pregnant or will suffer lifelong physical and mental injuries because of rape. The statistics are staggering.

Half of survivors are kids

Doctors Without Borders (DWB) reported in 2011 that 92 percent of females treated for rape in its Liberia facilities were under 18. A DWB study published in November said that of about 1,500 females treated in Monrovia clinics in 2008 and 2009 after rape, four out of 10 were younger than 12.

One in 10 was younger than 5. “Half of the survivors were children aged 13 years or younger and included infants and toddlers,” according to the report.

But shockingly only a small number of these cases ever make it to court. The Women and Children protection section of the Liberian National Police received 917 cases in 2012 but only 200 want to court. Out of 487 cases reported at the Sexual Gender based Violence Clinic run by a NGO called Touching Humanity In Need of Kindness (THINK) in 2012 only 4 were taken to court.

Olivia died of an infection in a Monrovia Hospital a week before Christmas. She was the fourth girl known to have died in Monrovia because of rape-related injuries in 2012 but experts say the number for the whole country is likely much, much higher. Most cases are never reported. Girls across the country are likely dying from untreated injuries caused by rape.

Gender Minister Julia Duncan Cassel and her team brought this case to light. It is also the subject of an international film to be released in the next couple of months. The minister says she mourns the death of Olivia today because according to her not much attention was given her death in the local media.

“The case is in the Supreme Court. The case is still there even though we heard the perpetrator is out. There are so many Olivias out there, if we don’t bring this case to light who knows how many others are dying from similar situations.”

According to Decontee’s father, she was raped one evening while going home. The accused perpetrator, who cannot be named in case because it would risk the prosecution case at trial, called her in his room and locked the door. The father only got to know when he discovered that she was pregnant.

Very Broken Justice System

Many families prefer, as Patience’s grandmother did, not to pursue the case at all.

“She wants to kill herself, so I have to stay with her all the time until things are settled,” he says.”

Getting things settled in Decontee’s case depends on Liberia’s very broken justice system. Just getting the perpetrator arrested can take months, before he even goes to trial.

In Decontee’s case the police told the father they have to complete lengthy investigations before arresting the accused rapist. It’s something the grieving father cannot understand.

“When they asked me this morning to come back to the clinic for the pregnancy test results I just broke down and started crying again,” he says.

“My daughter’s life is at stake; the boy is walking free in the community.”

“Since December I have been running to the police station up to now they have done nothing. They have the spoiled clothes and my baby’s statement. What are they waiting for to do their job?” he asks.

In the same clinic 9 year-old Patience walks like a cripple. She was raped by a 12 year-old boy two weeks ago. ”

“Patience’s case illustrates one of the big challenges faced by prosecutors in Liberia’s justice system. Patience’s grandmother, like Olivia’s family, chose not to go to the police but instead to settle the case, “the family way.”

“The boy is my neighbor’s son,” says the grandmother. “We eat and play together. I have boys children too so when they came to me begging I agreed not to go to court. Besides, that court thing can waste time and money. I just want my little girl to be all right.”

But Patience cannot forget about it. According to Madam Kekula, she has infections in her reproductive organ as result of injuries of the rape and may have to come at the clinic for over one month.

It will take some time to assess the full physical and mental impact on Patience but experts say she will likely live with this attack one way or another for the rest of her life.

“Our Major Challenge”

Olivia died of an infection in a Monrovia Hospital a week before Christmas. She was the fourth girl known to have died in Monrovia because of rape-related injuries in 2012 but experts say the number for the whole country is likely much, much higher. Most cases are never reported. Girls across the country are likely dying from untreated injuries caused by rape.

Indeed the court justice process takes a lot of time. Prosecutors in Liberia have no access to DNA testing and other forensic techniques that allow them to prove the perpetrator is guilty. It is often her word against his.

Testifying against an older man, a family member who has possibly threatened you, is a very difficult thing for many young girls. There is also a huge stigma that the girl will have to live with. The further the family takes the case the more people will know.

Many families prefer, as Patience’s grandmother did, not to pursue the case at all.

“Honestly that is our major challenge,” says Vera Mendy, head of the Women and Children Protection Section at the Liberian National Police. “We make follow up in the communities.”

“But sometimes the family relocates the victim. And we can’t get them through to the number they leave at the police station. We have also had situations where the community leaders and churches and mosques in some communities want to settle cases at their level.”

Doctors Without Borders (DWB) reported in 2011 that 92 percent of females treated for rape in its Liberia facilities were under 18.

Minister Duncan- Cassel also blames a lack of education among Liberians as to how the court system works. “Some of the reason we are finding from our own study is that a lot of our people are not educated to the importance of reporting these case.”

Just one court is responsible for all cases of sexual offenses. President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf created the court in 2008 with the goal of speeding up prosecution of rape cases. According to Vera Mendy, it has not had that effect. She says the court should be reformed.

Father getting exhausted

“We think that the court should be reformed just as the police was. Because we have had many cases that were investigated, case file prepared and sent to court; but the term of court is very slow.”

“In Montserrado we only one court for sexual Gender Based Violence with one sitting judge, and they have many cases.”

The court’s slow pace has contributed to the reluctance many families feel to pursue a long, painful court case that will expose their daughters to more suffering. For many a financial settlement with the perpetrator’s family is small consolation but they believe it is the only consolation they will ever get.

Back at the clinic Patience’s grandmother smiles bitterly as she says she knows that her action of compromise is wrong. “What can I do?” she asks.

“My hands are tied. I know what happened was bad. I thing made her sick, her skin was really hot and she was walking some kinda way. But I can’t carry that woman to court.”

At the same time Decontee’s father who wants to go court is getting exhausted at the slow pace at the system.

“Every time I see him I feel like doing something to him,” he says. “But I can’t take the law in my hands. I went to the police because I respect them. My daughter suffered the pains of abortion and she is still suffering his presence.”

Tecee Boley is a fellow of New Narratives, a project supporting leading independent media in Africa. See more at www.newnarratives.org

NOTE TO THE READER: The names of victims in this story are withheld to protect their identity expect for Olivia Zinnah who died due to injuries sustained as a result of rape.