Here in one of Africa’s biggest cities commuters have all the same needs as they do across the continent. But compared to other bustling cities, including Ghana’s capital, Accra, commuters here have a major advantage: modern public transport.

Among the taxis, cars and motorbikes that ply this city’s roads are a fleet of sleek buses and trains that whisk residents around the city quickly, cheaply and, importantly, cleanly.

Mr Ntsika Gqomfa, is a historian and tour guide at the Constitution Hill, one of the city’s biggest tourist attractions. He is a regular user of the city’s Rea Vaya, a public rapid transport bus to and from work. He says it saves him the equivalent of GHC800 a year.

The speed and cost are major appeals for Mr Gqomfa but he is also mindful of the reduction in air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions that come from the buses. These operate on low-sulfur diesel that emits fewer pollutants saving a million tonnes of unhealthy and harmful gases.

“They beat heavy traffic congestion and make sure people get to work early. I am also happy to be contributing to low emissions,” he says.

On a busy week day in November commuters from all walks of life testified to the efficiency, affordability, and cleanness of the recent transport system.

The length of a Rea Vaya bus is twice that of Accra’s own rapid transit bus system, the Ayalolo, introduced in Accra in 2016. It can accommodate 90 passengers, or the equivalent of four benz buses at a go.

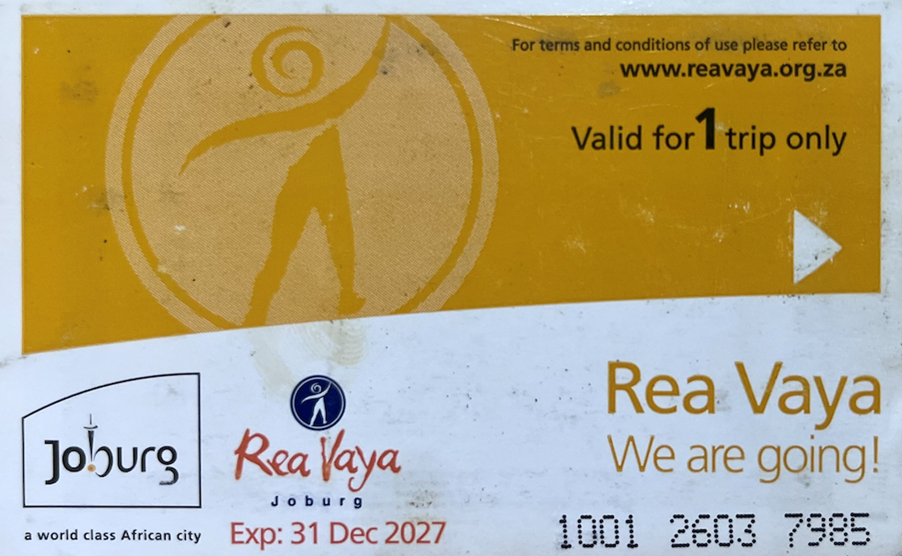

After buying a pass, passengers swipe at the turnstiles inside the bus station and wait for their bus, which is usually announced. It arrives quickly, and passengers board taking seats or standing in designated areas with rails for support. The bus moves quickly and quietly on its own dedicated street lanes, which allow it to avoid major traffic congestion.

Challenges, success lessons

The Rea Vaya, which links the Johannesburg Central Business District with several major townships was introduced in 2010 as the city was hosting the Football World Cup. After the upheaval of the post-apartheid period after 1994, the city was under pressure to showcase its best self to the world and show that it could handle an event of that scale.

Rea Vaya means – “we are going” – and it does just that, transporting an average of 16,000 passengers each week day.

However, the Rea Vaya BRT encountered significant opposition from the taxi community here. Taxis – the equivalent of “trotro” minibuses in Ghana – have a powerful lobby here and they were concerned about competition and a loss of income – one bus replaces 40 cars or several minibuses.

But negotiations, aided by officials from the New York Institute for Transportation & Development Policy and GIZ, the German government development agency, led to 350 minibus/taxis being withdrawn from service and their drivers retrained as bus drivers.

While Johannesburg transport officials were motivated to reduce congestion on the city’s rounds they were also keen to reduce the city’s emission of greenhouse gases and air pollutants.

Nonetheless, there are problems: The bus is in high demand and that makes it slow at times. It does not yet operate in other key areas of the city but experts say the Rea Vaya is a strong example that safe, reliable and low emission public transport can be done on the African continent. Johannesburg is one of few cities on the African continent with a modern public transport system. Other major cities such as those in Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, Ethiopia and Senegal do not have a modern public bus transport system.

Experts say that will have to change as African populations increase rapidly in the coming decades and air pollution takes a greater toll on human health. According to a 2021 UNEP Air Pollution and Development in Africa report, increased levels of outdoor air pollution in Africa could be the beginning of “a looming problem” – becoming a much larger cause of disease and premature death, while posing a major threat to economic development.

A number of studies have found that greenhouse gas emissions, which also cause harm to human health, from transportation is a big challenge in Africa. This is isaid to be growing at a rate of seven per cent annually. Poor fuel quality, aging vehicle fleet, and lack of mandatory roadworthy emission tests are to blame for the deteriorating transport emissions, according to experts.

Rea Vaya vs Ayalolo

Accra’s Ayalolo is Ghana’s closest attempt at a modern public transport system. In a bid to improve mobility, Accra Metropolitan Area officials approved a Bus Rapid Transit, known by the acronym BRT, in 2007. Delays and unhealthy politicisation of the programme meant the pilot did not begin until nearly a decade later in 2016.

Successive governments and the private sector have not been able to fulfil the objective of the project, experts say, due to poor implementation, thus leaving part of the $151 million investment such as the buses in ruin.

Johannesburg’s system served as a role model for the project according to Mr Alhaji Abass Imoro, the Public Relations Officer of the Ghana Private Road and Transport Union, the largest transport union in Ghana.

“We were sent to Johannesburg to witness their transport system years back. Everybody liked it,” Mr Imoro says. He accuses the government and stakeholders of not implementing the project as planned.

Mr Imoro says that in the implementation plan buses were supposed to have been given to the unions to operate and pay proceeds to the government with Greater Accra Passenger Transport Executive, known by the acronym, GAPTE, playing a supervisory role.

“This did not happen. The lanes that were to be provided were just a few. So, if you ask me, I will say the rules were not followed. That is why Ayalolo failed,” he said.

On paper, the government’s role was to provide infrastructure, GAPTE, regulates, while GPRTU operates but that did not happen, according to Mr Jonathan Botcwey, Board Member of the Ghana Cooperative BRT Joint Operations Management Committee.

“Such legacy project should be devoid of political influence and be left to technical people to implement it,” Botcwey said.

A study by transport researcher Edmund Teko, at the University of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, backs Botcwey’s claims finding that political interference in the implementation caused the project to fail. Teko recommends sector reforms precede future implementation of such projects.

“…executing BRT concurrently with institutional reforms proved to be a risky task; as the distrust among transport operators led to prolonged resistance and opposition to sector reorganization initiatives and jeopardized the chances of successful implementation,” the study said.

Mr Desmond Appiah, Country Lead of Clean Air Fund, says leaders do not know the benefit of such a project to the health and economy beyond providing an efficient transport system.

“Government spends so much money treating respiratory illnesses linked to air pollution annually through the National Health Insurance, however, investment in projects to control such public health emergencies will prevent deaths and people getting sick,” he says.

It is important that governments support an efficient system like the Johannesburg or the London transport system, but they need to know real economic advantage before making such investments, Appiah adds.

*****

This story was a collaboration between Ghana News Agency and New Narratives as part of its Clean Air Reporting Project. Funding was provided by the Clean Air Fund. The funder had no say in the story’s content.