Monrovia – Stephen Rapp, former United States Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice and Dr. Uchenna Emelonye, Country Representative of the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights have both called for Liberia to set up a war crimes court to prosecute perpetrators of its civil war.

This story first appeared on FrontPageAfrica as part of a collaboration for the West Africa Justice Reporting Project.

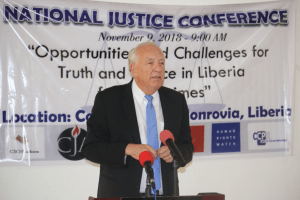

The gathering was the first of its kind since the end of the TRC process, which organizers say is an evidence of the growing momentum for war accountability in Liberia. It was held under the theme “Opportunities and Challenges for Truth and Justice in Liberia for Past Crimes”.

Mr. Rapp said after 15 years since the end of the civil war, Liberia could not set up the court at a better time.

“We very much recognize to prevent atrocities in the future—murder, rape, the burning and destruction of homes and communities and livelihoods—one needs to hold responsible, at least the major actors of those crimes, to account,” he told the conference in a special message, warning that leaders in the future could take advantage of impunity to return the country into a bloodbath. “The only way we can prevent that is by the way we prevent other crimes: by holding those that are responsible in fair processes,” he said.

Ambassador was the Chief Prosecutor for the UN-backed Special Court for Sierra Leone that prosecuted former President Charles Taylor now serving a 50-year prison sentence for aiding and abetting crimes in neighboring Sierra Leone. Before that Rapp was a prosecutor with the International Criminal Court for Rwanda.

He said he was in support of the TRC-recommended court, with both local and international judges. “The government of the United States…is always to always work with the national system,” he said. “If you can get it done, if you can have justice through a normal national system with additional support, that’s the preferred alternative because that builds and sustains the national system.”

Rapp further noted the failure of the Liberian government or the international system to prosecute Benjamin Yeaten, former Director of the defunct Special Security Services (SSS) for his alleged crimes proved that national and international collaboration was a must for Liberia. He said such collaboration would assure funding for the court, as Liberia could not support the court on its own.

He called on the public for patience as justice creeps its way into Liberia, and stressing that the court did not hold all the solutions to Liberia. He said countries such as those coming from the former Yugoslavia and Sierra Leone do have problems but are experiencing the reduction of violent crimes such as rape and murder due to the bold step to prosecute major actors.

“I think it is very important to prevent crimes, to deter, to protect our children, our grandchildren that we do make the decision for justice,” he said. “Today I see the swelling of interest for justice to be delivered in country,” he added to huge cheers from conference delegates.

Dr. Emelonye of the Office for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights said justice for Liberia was an imperative. Pledging the UN’s fullest support to civil society organizations and the government, Dr. Emelonye justice for all, including war crimes committed in the past would accelerate and consolidate Liberia’s peace.

“A postwar society that does not promote justice and accountability, does not properly heal without scars,” he said. “If the victim of today does not heal and forgive, there is a tendency that he or she will be the violator tomorrow…” he added.

“The tested and trusted healing therapy for victims of post conflict atrocities is accountability.”

The UN Human Rights Committee in July this year gave Liberia until 2020 to address war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during its civil war. Liberia made a commitment to issue a statement on how it will address wartime crimes, but the current administration has said it does not prioritize the court.

Dr. Emelonye said justice had everything to do with the government’s quest for development. “Liberia’s laudable Pro-Poor Agenda [for Prosperity and Accountability] and its frantic efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly goal 16, which focuses on peace, justice and strong institutions, will be facilitated if the government builds a peaceful and inclusive country that is governed by accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels,” he said.

Liberia fought one of the 20th Century’s bloodiest civil crises (1989-2003) that killed an estimated 250,000 and displaced up to a million people.

The Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) recommended nearly 10 years ago that the court to established but that has yet to happen.

A rare scene of the event was the gathering of four former TRC Commissioners: Commissioners Massa Washington, John Stewart, Dede Dolopei and Pearl Brown Bull. Bull was one of two commissioners who did not sign the TRC report, while Dolopei signed but with reservations. It was the highest number of former TRC commissioners at any program in nearly a decade.

Former Commissioner Washington joked—in dig at former President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf—that commissioners were still in the employ of the commission since it was not decommissioned. That, too, was a recall of the controversies that characterized the end release of the TRC report.

“After 10 years this is the moment,” Washington, who was an editor with the Inquirer newspaper and an advocate throughout most of the war said. “So much efforts have been expanded over the years, rigorous but failed attempt to denigrate the TRC report,” she lamented. “But now there is light at the end of the tunnel and the hope for victims for justice appears to have been given a new boost.”

Representive Suacoco Dennis (Montserrado District 4), the Chairman of the House of Representatives’ Committee on Claims and Petition said it was important to end the culture of impunity if it stagnated the country’s development.

Bartholomew Colley, Vice Chairman of the Independent Human Rights Commission, which supposed to implement the TRC recommendations, said prosecution of crimes was legal, adding “Human Rights violation is a zero-tolerance issue.”

The conference was organized by the Global Justice and Research Project (GJRP), Swiss-based Civitas Maxima, the Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA) of the United States, The Advocates for Human Rights and the Human Rights Watch.

Addressing delegates question of fear and security when the court is finally established, Hassan Bility of GJRP said the “Fear has shifted from the victims to the perpetrators, borrowing the words of Cllr. Tiawon Gongloe, a human rights lawyer.