Clothing designer Geneva Garr supervises several men crouched over sewing machines surrounded by beautifully tailored dresses hanging for customers to see. Starting up with just one sewing machine on her porch, Garr, 37, now makes 72 outfits a week.

Garr says she started the business in 2005 in Accra, Ghana and moved to Liberia in 2008 once she was sure peace was restored. Garr advises other would-be entrepreneurs to think big no matter how small they are at the start.

“Some people just want to inherit a large property or get this big money to start,” says Garr. “I started with my one machine on my porch. So start with the little that you have, and don’t be afraid to venture.”

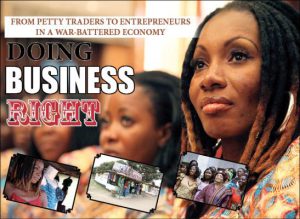

Owner of Approved Wear Fashion House on Duport Road in Paynesville, Garr is among many Liberian business people faced with considerable obstacles as they transition from being petty traders to full-fledged entrepreneurs. They say growing a small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) in postwar Liberia is not easy.

[B]‘A lot of challenges’[/B]

“Liberia has a lot of challenges,” says Sam Mitchell, former president of the Liberia Business Association, an umbrella group for Liberian entrepreneurs, and owner of the Corina Hotel in Monrovia. “If you talk about manufacturing, we are far away from that. Electricity is still not stable. There is also the problem of skills and implementing SME policies.”

Garr now commands a staff of 11. Most are men because, she says, they can better handle the physical demands of the high rate of production. But finding Liberians with the right skills and training was a long struggle.

“The major challenge I faced was recruiting qualified designers because I wanted designers who would understand my work style, the way I like my stuff to be done, the way I want it to be made,” she says. “I wanted designers who I would just do a sketch, explain it, and they grab it.”

Garr initially couldn’t find such designers in Liberia, she says. Many have criticized the educational system for not creating an avenue for Liberians to acquire the professional skills needed to succeed in business.

“The average Liberian does not have the skill, does not have the tradition – as some of our friends and neighbors have – of being traders,” says Mitchell. “In order to build up this class, we have to work to make sure that the curriculum in schools and universities is related to job creation, to opportunities.”

[B]‘Didn’t go to Design School’[/B]

“The universities only teach for the office, so when you graduate you can only apply for an office job,” says Garr. Garr says she had to practically train her staff from scratch because they did not have the specialized skills her business demanded.

“Most of the guys I found here were people who were like apprentices,” says Garr. “They didn’t go to designing school like I had the privilege to do. They just learned by watching in the tailor shop and stuff like that, so it was a major challenge.”

Access to finance in the form of microcredit is another hurdle. Many of the banks require collateral that ordinary Liberians do not have, so they are treated as high-risk borrowers for loans.

“Microcredit is very expensive because the risks are very high,” says Mitchell. “Most of the petty traders are first-time borrowers, and it’s a high default rate. So when there is a high rate of default, there is a high rate of interest and penalties.”

Garr says there were times she feared her business would never get off the ground. Then help came in the form of her first big contract.

“My first big breakthrough came from a uniform contract that I did for a local school called Kingdom Builders International School,” says Garr.

“I did about 250 pieces of uniforms. I took that contract as a challenge. I was sewing all by myself. I used to work day and night doing those uniforms. And I used the funding from the uniforms to get a place on the road.”

Garr also is one of the lucky few that have received loans from a local bank without any collateral requested. She was able to pay back her first loan early, which then enabled her to get a second loan to grow her business further. Being disciplined with the money was critical to her success, says Garr.

[B]Loan for Flashy Cars[/B]

“Most of the time, our colleagues get the loans, but they don’t invest the money into their business,” says Garr. “They get the loan and buy flashy cars, build houses with the loan, and then to pay the loan back becomes difficult.”

Another stepping stone for Garr was graduating last month from the 10,000 Women program, a project backed by United States banking giant Goldman Sachs and run in Liberia by US non-profit organization CHF International.

The program provides training for women entrepreneurs around the world. The classes gave her the know-how to do better business, says Garr.

“At first, I was just doing business with just me, my manager and my staff,” says Garr. “It taught me how to manage my human resources, how to keep my financial records, and how to separate my personal money from my business.”

“We carry on business wrap-around services, and we try to train women to graduate from the level of petty traders to entrepreneurs,” says Josephine Flomo, business advisor for the 10,000 Women program in Liberia.

“We also train them to get some business education and some training in different areas like marketing, customer service, how to pay their taxes within a targeted period of time.”

But an initiative like 10,000 Women alone is not enough to make a substantial impact to Liberia’s enterprises and economy. That requires strong government support, says Mitchell.

[B]Steady growth[/B]

“We need to promote Liberian entrepreneurship,” says Mitchell. “We don’t do that.” At last month’s 10,000 Women graduation ceremony, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf acknowledged this need.

“Government, too, has an important role to play to create the conditions for business to grow and flourish,” said Johnson Sirleaf.

“We therefore adopted the first national Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Policy to provide a framework for government’s and other stakeholders’ support to micro, small, and medium enterprises.”

The 14-year civil war left almost all of Liberia’s infrastructure in ruins and just $100 million in annual revenue. Under President Johnson Sirleaf, there has been steady growth in the economy. Although this has yet to trickle down to the average Liberian, Mitchell is optimistic that the challenges can be overcome.

“The Liberian economy is on the ascendency,” says Mitchell. “When you break down an economy, the only thing you do is build it up, and that’s what we’re doing.”

Garr, too, continues to work her way up. The price tag for a Garr-designed lapa dress is about US$50. She also recently won a contract to create uniforms for petroleum company Total Liberia.

Garr makes a profit of about US$300 – $400 per week and invests it all back into the business in the hope of taking it to the next level. She wants to open a small factory where she will be able to employ more people and make more profit.

“To have about 20-30 workers on the machines, my production should be moved from 72 to 150 suits a week – that’s what I hope to produce,” she says.

“I want to be able to make clothes to be sent to department stores, be it in the US or here or in other African countries.”

[B]Wade Williams is a fellow of New Narratives, a project supporting independent media in Africa. Please see more at [LINK=https://newnarratives.org/]www.newnarratives.org[/LINK][/B]