MONROVIA, Liberia – The future was bright for Doboe-Blee Garley, a 20-year-old, newly-married man in 1926. Well built and outstanding in the Menson Clan of Tchien District in Grand Gedeh County, Garley was a great royal hunter and a farmer. His wife, Munah, had come from a long lineage of traditional priests. Excitedly, the newlyweds made their way to the seaport city of Greenville to buy lapas, salt, and dishes for their home, according to citizens of Pelezon and Garley’s 62-year-old niece Theresa Boryea Walo, to whom the late Garley told his story.

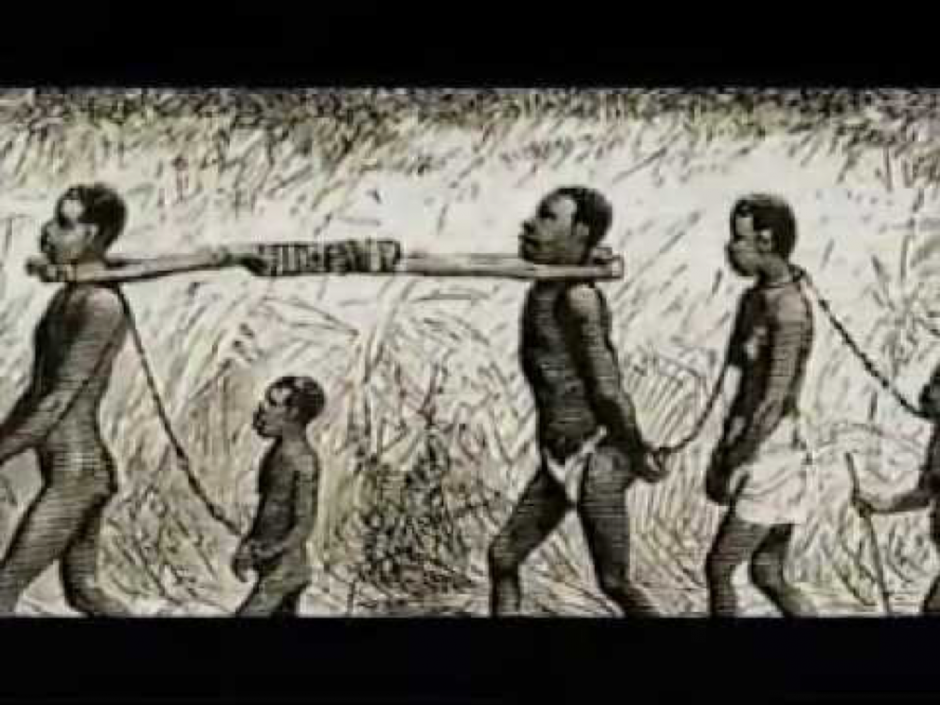

But everything changed when Garley was captured by troops working for top Liberian government officials who were tasked with forcibly recruiting people to work on the Spanish-owned sugar cane, coffee and cocoa plantations in Fernando Po (located in current day Equatorial Guinea and parts of Gabon). Many of these forced recruits were abducted from the southeastern region of Liberia. Munah waited as the days turned to weeks and the weeks to months but her husband did not return. After six months she walked alone on the 155-kilometer bush road back to Grand Gedeh. It took her weeks to reach home. When she finally reached, she ignored pains of the sores in her feet and ran around Pelezon Town beating her breast and crying as she told her ordeal.

“When she reached home there was crying and mourning in the entire Clan. Other men were also forcefully taken to Fernando Po. According to the elders of this land, Doboe-Blee Garley case was extraordinary because whenever there was famine, people would go to him for food,” said Walo.

Garley was one of thousands of young men, who was abducted with the complicity top Liberian government officials of Africa’s first republic that was founded in 1848 by freed slaves. Garley was likely captured between 1926 to 1929. According to historical accounts, the President, Charles D.B. King, his Vice President Allen Yancy, and the Speaker of the House of Representative Samuel A. Ross were directly involved in the forced recruitment. They were receiving £8 British pounds per head for recruiting and shipping their citizens off to labor camps on sugar cane, cocoa and coffee plantations.

The Liberian government argued that “slavery as defined by Anti- Slavery Convention, in fact did not exist in the country.

But, the League of Nations committee found that, “shipment to Fernando Po and Gabon is associated with slavery because the method of recruiting carries compulsion with it. Persons holding officials positions have misused their office in recruiting with aid of the Liberian Frontier Force,” according to the website liberiapastandpresent.org.

“The conditions under which people were being arrested or being captured and shipped up to faraway Spanish Island, violated these people rights as far as that convention [The Convention to Abolish Force Labor and Slavery which Liberia was a party to] was concerned. People got killed. Some people never returned. Some of those who returned died after few weeks,” said Aaron Weah, the Liberian country representative of Search for Common Ground, an organization that works to mitigate conflicts through dialogue and mediation.

Munah waited for her husband Garley for another six months. But, her husband did not return. Munah remarried and moved on. However, her husband did not forget her.

“My uncle did not rest,” said Walo. “He told me when I was a girl that he thought about his young wife all the time. She was tall, black and beautiful with long hair. He decided to run away and come home. He avoided some meals in the day to save money to come home. He made £1.50 monthly. When he finally got £35 pounds, he paid some people on a ship to take him to Sierra Leone,” said Walo.

It took Garley about two months walking from Freetown to reach Monrovia. He stayed for about three months before finally deciding to walk home. In those days there were no taxis or cars traveling to and from the hinterlands.

“When he finally reached home it was too late. He had stayed too long. The woman he so loved had remarried and had 1 child,” said Walo.

As unfortunate as Garley’s story seems, he was one of the lucky ones. He returned to his people. Many who went to Fernando Po died or remained there. For those who never returned, the women of the South East sang in their languages to remember them. One chant translated from the Grebo tribe said:

“Allen Yancy where are our sons?

Where are our husbands?

You have left us without husbands

And sons

Oh Allen Yancy!”

Liberian Historian, Dr. Joseph Saye Guannu said there are still traces of those who never made it home.

“If you went to Equatorial Guinea today you will notice that descendants of those people are still there, maybe in their languages and the culture (maybe similar to South Eastern Liberia culture),” said Guannu.

Garley later remarried and had two sons. One is dead. The other son Borbor Solo Johnson lives alone on the original spot of Pelezon Town where his father returned to. At 80 years old, Johnson still remembers some of the deeds of his father.

“Maybe because of what happened to him, my father was a just man. He was a judge of the entire Clan. He was always called upon to settle disputes in the land. He spoke truth to the faces of people no matter who they were,” said Johnson.

The situation of Garley and others reached the attention of the League of Nations after defeated candidate Thomas Faulkner accused President-elect Charles D. B. King of allowing slavery to exist in Liberia. The League of Nations commissioned an inquiry into the allegations. They found that it was true that slavery indeed existed. This led serious threat to Liberia’s independence. The League threatened to take Liberia into trusteeship, like other Africa countries.

“Liberian did not fully cooperate with the League of Nations. At the end of the day, the League of Nations withdrew its interest in the case because Liberia played delay tactics,” said Dr. Guannu.

Aaron Weah suggests there are parallels with the outcome of the League of Nations inquiry and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, that recommended key perpetrators of war crimes and financiers of the war for prosecution in its final report in 2009.

“The League of Nations Inquiry was mandated to investigate allegations of the practice of slavery in Liberia while the TRC was mandated to investigate the root causes of the Liberian civil war and advance measure that to prevent the re occurrence of war/aggression. However, there are some notable similarities to consider,” Weah said.

Both inquiries were internationally backed and involved statement gathering from victims. Both had a “profound impact on society,” and both inquiries failed to satisfactorily implement their recommendations.

“The lack of implementation of these reports’ important recommendations sends a negative message against justice and accountability and that wrongdoers can continue to perpetrate harm and nothing will be done,” said Weah.

However, during a recent speech at the United Nations General Assembly, President Weah indicated his willingness to consider the implementation of the war crimes court and recognized “the rising chorus of voices from many quarters calling for the establishment of a war crimes court.”

While many of the men who were sent to Fernando-Po have disappeared, those wounded by the Liberian civil war remain.

One of the victims of the war is 47-year-old Mamie Barwone. Today, she lives in Saclepea, a life much different from that she lived in Monrovia in 1989. Like Garley, Barwone’s life was changed by the war. She was planning her wedding for the second week in July of 1990, when a grenade exploded killing in her living room, killing six people and leaving her maimed.

“All over my body are marks. They had to take out the iron them [particles] from my body,” said Barwone, whose bones were broken by the explosion.

She is yet to receive reparations or justice for the crimes committed against her.

For Boryea Walo, holding those accountable for kidnapping her uncle Garley is impossible now. However, holding those who committed crimes during the civil war that ended in 2003 is a must.

“But all the people who carried my uncle to Fernando Po are dead. How will they go to court now? As for the current call for war crimes. I say all of them must go there so that other people will not do what they did here,” Walo said.

This story first appeared on FrontPageAfricaOnline as part of a collaboration for the West Africa Justice Reporting Project.