MONROVIA – The conversation about setting up a War Crimes Court in Liberia has intensified in the last 18 months. This is partly due to a push by local and international advocates for accountability, finally, for the brutality that claimed the lives of 250,000 Liberians. They’ve seen an opportunity in the election of President George Weah, a man had no ties to warring factions and who has voiced support for a court in the past.

This story first appeared on FrontPageAfricaOnline as part of a collaboration for the West Africa Justice Reporting Project.

But what precise steps will it take for a war crimes and economics court to be set up for Liberia’s civil war? And what crimes will it try?

What are War Crimes?

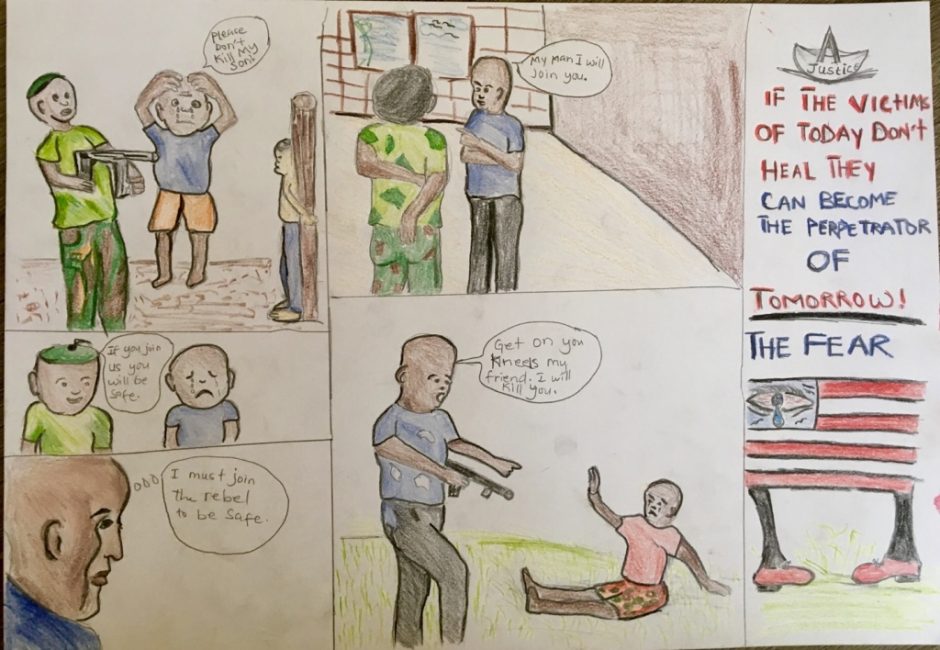

“War crimes” are crimes committed during war, including intentional killing of civilians or prisoners, torture, rape, recruitment of child soldiers and, among others, pillaging. Many of the crimes committed in Liberia’s civil war fall under this definition. Unlike many crimes, war crimes have no “statute of limitation”. That means they can be prosecuted regardless of how long ago they were committed. This is important now that the start date of hostilities approaches the 30-year-anniversary.

Liberia is a treaty party to the United Nations Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR), which mandates state-parties to prosecute war crimes. The United Nations CCPR says, a State party should, as a matter of priority, establish a process of accountability for past gross human rights violations and war crimes that conforms to international standards, including independence and expertise of the judiciary, victims’ access to justice, due process and fair trial guarantees, and witness protection.

“The state party should in particular, ensure that all alleged perpetrators of gross human rights violations and war crimes are impartially prosecuted and, if found guilty, convicted and punished in accordance with the gravity of the acts committed, regardless of their status or any domestic legislation on immunities,” the Treaty says. It also calls for the removal of “any persons who have been proven to be involved in gross human rights violations and war crimes from official positions.”

The UN Human Rights Committee meeting in July last year determined that Liberia had waited long enough. They directed the Weah administration to put in place a justice process that meets this criteria by July 2020. After that date the government will face increasing pressure, possibly including sanctions and exclusion from international organizations, committees and financial support.

Political Will

Despite Liberia being a signatory to the CCPR, and having the TRC report as a guide, there still needs to be a political will for the court to be set up in the country. The president has to endorse the process for the setting up of the court and it has to go through the Legislature.

Since his election President Weah has shown no will to create the court despite calling for a court in 2004. Many commentators say Weah formed a political alliance with Senator Prince Y. Johnson of Nimba County—one of the “most notorious perpetrators” listed by the TRC— that Johnson would support his candidacy (and urge electors in his vote-rich county of Nimba to also vote for Weah) in return for Weah’s refusal to hold a court. Weah also has appointed some people named as perpetrators by the TRC Report to government such as Kai Farley, Superintendent of Grand Gedeh County.

In public Weah has said a court would threaten the stability of the country.

“Do we need war crimes court now to develop our country or do we need peace to develop the country?” President Weah asked in November 2018. “That’s where all of us Liberians need to sit and talk about advancement and what is necessary for us.”

“When people become politicians, they tend to see things a bit differently, and the view of the President on the matter is a little different now,” says Aaron Weah, an official with the TRC and now head of Search for Common Ground. “But what is really different in my view, is that the very people who elected George Weah are growingly becoming impatient about the government’s lack of direction on the matter, and for some people refusing to forgive brings them some form of healing, control and power over their perpetrators. If you forgive you give away everything you have, and for some people they get even more hurt when they just forgive without being prepared.”

Adama Dempster, the Secretary General of the civil society human rights advocacy platform, a network of pro human rights organizations in Liberia, calls on President Weah to choose the interest of majority of the people who voted for him over the interest of the people in his power bloc. “If the president thinks that those political marriages he got involved with will be good for him, his thoughts are on the contrary, because it’s not about his benefits or did he sacrifice the interest of the vast majority of Liberians because he wanted to come to power?” Dempster asks.

The Legislature has not made any official statement about the establishment of the court yet, even though some members have expressed in the court being set up. But a committee, Claims and Petition, was set up to look into such matter .

In May last year, a group of Liberians under the banner Citizens United for the Establishment of War and Economic Crimes Courts, petitioned the Legislature to set up the court. There has been no answer to that petition so far. On the prospects of a bill supporting the court, the Chairman of the House’s Committee on Claims and Petition, Representative Rustorlyn Dennis says, “to call for the establishment of a war crimes court means votes will be needed and the bill needs sponsor.”

Fubbi Henris, who heads the Citizens United for the Establishment of War and Economic Crimes Court, says he’s increasingly frustrated over the issue. “In fact, the Speaker has on several occasions undermined the petition by openly saying that he will not append his signature to anything for prosecution or retributive justice, and that alone speaks volume,” he says.

Which crimes will be prosecuted?

Many in Liberia feel the start of the country’s troubles began way before the Christmas 1989 rebellion by Charles Taylor. Some would like to see prosecutions go back as far as 1980 and the coup by Samuel K. Doe. For the purposes of the court the dates of crimes that are eligible for prosecutions will start with Taylor’s invasion when the first shots were fired and the war officially began.

What will the Court look like?

For the court to be set up, there must be a structure in place. The TRC Report states that in order for the recommendations to be implemented, “an internationalized domestic court” or an extraordinary criminal court must be established, comprising two chambers and 12 independent full-time judges.

There will be two chambers – one will be the trials chamber. The second will be appeals chamber that will decide on disputes that arise in the trial. Six judges will serve in the appeals chamber, two of which will be appointed by the President of Liberia, two judges appointed by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, one judge by the President of the European Union, and one judge by the Chairman of the Commission of the African Union. These Judges will only serve in the chamber to which he or she has been designated, and Judges from each chamber will be elected by a majority, a presiding judge who will conduct the proceedings in his or her designated Chamber. The presiding judge of the appeals chamber will serve as the president of the court.

It is required of the president of the court, according to the TRC report, to be competent in order to make general and special assignment of judges to any chamber or panel consistent with the court’s rules of evidence and procedure.

Two alternate judges will be appointed by the Government of Liberia, one will be assigned to the trial chamber and the other to the appeals chamber. In the event of a vacancy the appointing authority retains the right to appoint alternative judge(s) will be subject to the approval of the President of Liberia. It is imperative that least a third of all of the judges must be women, the report says.

The report adds, that judges of the Court “shall be persons of high moral character, integrity and impartiality who have expertise in public international law or Liberian criminal law, and have at least 10 years of legal experience, receiving the same privileges and immunities as judges of the Supreme Court of Liberia.” It goes on to say that judges must not be in the employ of any other entity or hold office in political organizations, political associations or foundations connected to them, nor be involved in any political or party activities of a public nature. The only exception to this rule will be professorial duties or research of legal nature, the report recommends.

Foreign judges appointed by the UN Security Council will be entitled to full diplomatic privileges and immunities of foreign diplomatic personnel.

The extraordinary tribunal for Liberia does not necessarily have to be a UN-backed court. It can as well be an African Union-backed court. Liberia is a member-state of the AU and regional body prohibits war crimes and crimes against humanity like the UN. A typical example of this is the case of Hissene Habre, the ex-leader of Chad. A special African Chamber in Senegal found him guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity in May 2016.

There is a growing concern about the protection of witnesses and security if the court is established, but pro-justice campaigner, Adama Dempster is confident the international community will provide training and financial support for security.

He noted that people who will be recruited from Liberia, will also be trained to international standards to be able to work along with their international colleagues.

Court in Limbo

Despite President Weah’s lack of public support for a court, Aaron Weah says he is optimistic that the court will be created. “What I see as the first major step is that there’s a growing interest of Liberians all around the country,” he says.

There is indeed growing interest in the court. Aaron Weah, Dempster, Peterson Sonyah—the head of the Liberia Massacre Survivors Association (LIMASA)—and other pro-war crimes court advocates have established a secretariat for the establishment of the court.

Though no credible survey has yet been done evaluating popular support for a court, New Narrative Liberia journalists working across the country have seen dramatic increases in support for a court among Liberians.

Dempster and colleagues have begun holding conferences around the country on transitional justice, including criminal accountability, to help Liberians everywhere understand the process and to dispel any fears.

The international community has given it heavy backing. In addition to the UN Human Rights Committee, Amina Mohamed, Deputy Secretary General of the UN, voiced her support for a court. Scores of international human rights groups such as Amnesty International, Civitas Maxima and Human Rights Watch, have called for the court. Alleged Liberian war criminals are being tried overseas for their roles in the country’s civil war.

Despite the inaction by the president and legislature, justice advocates say it is only a matter of time before the country gets a court. Aaron Weah says it is unthinkable to many that Liberia should go on with impunity for a brutal war that did so many damages to people, infrastructure and the country’s future.

“The whole idea around the war crimes court is about changing the course of the Liberian history, and holding people accountable.”