Liberia is one of just three West African nations where female genital cutting is legal. In this two-part series with New Narratives Evelyn Kpadeh Seagbeh finds strong resistance to the bill from traditional leaders and little political will to challenge them. At the same time Sande’s membership is plummeting.

MOUNT BARCLAY, Montserrado – 18-year-old Dearest is one of five girls who made headlines last year when they were abducted and forcefully initiated into the Sande Society here. Nearly a year on she is still angry and traumatized.

What Dearest most wants to see is the women who abducted her prosecuted for their crimes. She is pleased to hear that a new bill before the legislature would do that.

“I will be so glad to hear that they have put stop to FGM finally in Liberia,” says Dearest using the acronym for the term widely used by activists to describe the practice of “female genital mutilation”. Her real name is being withheld for her protection. “Let that law have a punishment for those who force girls into the Sande because, the lady who forced us into the Sande has been passing around boasting how we were never going to go back to school again, and she goes about boasting and making big mouth.”

Liberia currently has no law against female genital cutting unlike all but two other West African countries. Conducted by Liberia’s centuries-old traditional societies, FGC is part of an initiation ceremony for girls. Several attempts have been made to ban the act, which causes lifelong pain and health problems for most women who endure it. It is cited in many international human rights conventions to which Liberia has signed including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol).

A new bill before the Liberian Legislature could change that. The draft act, entitled “An Act Prohibiting Female Genital Mutilation 2022” would criminalize the cutting of girls under 18. Submitted by Deputy Speaker of the House of Representatives Fonati Koffa, the has been before the House Committee for review and recommendations since June.

International partners including the United Nations Population Fund have celebrated the government’s move. But Liberian activists are far less enthusiastic.

Tamba Johnson, founder and national coordinator of He For She Crusaders Liberia and member of the civil society working group on FGC, says traditional leaders’ disdain for the Liberian constitution and any efforts to force them to comply with the laws and functions of a modern Liberian state, casts a cloud on the process.

“Of those 73 lawmakers, very few of them will support our bill,” Johnson says. “This is because many of them want to get reelected and they want to buy the sentiment and support of the traditional people. They may say that Fonati Koffa is from the Southeast where the practice is not taking place, so they will be playing games with the traditional people to buy their support and at the same time playing games with the international community to make it appear that they are in the interest of best practice to end FGM.”

Lena T. Cummings, a leading women’s rights advocate and former executive director of the Women’s NGO Secretariat of Liberia (WONGOSOL), shares Johnson’s pessimism. Cummings’ institution -WONGOSOL was one of the organizations that supported and raised awareness about the country’s Domestic Violence bill in 2019 which originally inlcuded a ban on FGC. It was eventually stripped from the bill before it was passed.

“We have had lots of campaigns and so many things and yet people still walk with impunity, so for FGM and the strong traditional ties to have it stopped before the 2023 elections, I am not very optimistic,” said Cummings.

The actions of the legislators themselves appear to underscore the cynicism of activists. Even those legislators who have backed the bill – Speaker Koffa and Rustolyn Dennis – ignored repeated phone calls and texts requesting comment for this story.

Bong County Representative Moima Briggs Mensah agreed to an interview but then did not pick up calls on the agreed day.

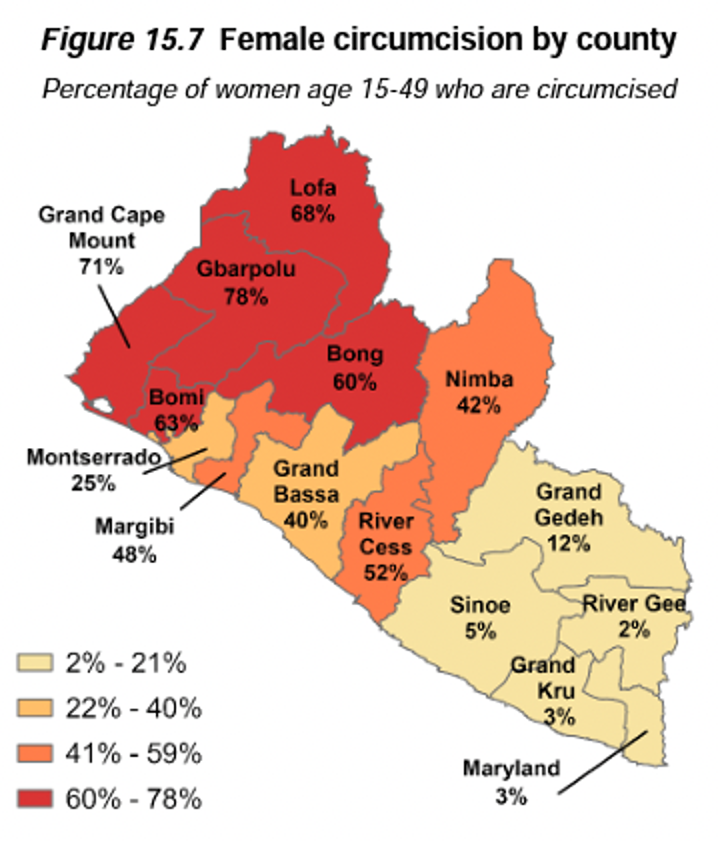

Bong County is a heartland of the powerful traditional societies – Poro, for the men and Sande, for women – which take children and teenagers to “Bush schools” for six months or up to a year to teach them to be adults. The major groups that practice it are the Mande-speaking peoples of western Liberia such as the Gola and Kissi. It is not practiced by the Kru, Grebo, or Krahn in the southeast, by the Americo-Liberians (Congos), or by Muslim Mandingos.

Women are taught to be wives and mothers and discouraged from taking part in the formal education system which is seen as a western import that runs counter to traditional values.

The Bush schools end in an initiation into the traditional society. For both sexes that means circumcision. During the ceremony, traditional leaders known as “zoes” cut the girl’s exterior genitalia off, usually with a razor blade.

Opposition to the anti-FGC law has been strong. Chief Jimmy Gboyon Kollie, a well-known traditional chief in Bong and head of zoes, raged with anger about efforts by the legislature to ban FGC. Chief Kollie is warning legislators not to pass the law.

“My message to the lawmakers is that we do not agree and we are calling on them not to pass that bill,” Kollie said in a phone interview from an undisclosed location in Bong where he was running a bush school. “We, the country people, respect our tradition and that we that are into it, the women’s society and we, the men, we have our traditions, but we all cannot agree for the women’s society to stop. Every country and every tribe including the civilized people have their societies so why is it that they want us the native people to stop our society?”

President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf placed a one-year ban on FGC as she left office in 2018. Another ban followed and this year a third ban was put in place. But many traditional leaders have just ignored it according to Johnson.

“We have reports that seven communities in Lofa are still engaged in the practice even with the current three-year suspension on FGM now,” Johnson said. “FGM is still happening in Margibi County, Montserrado, Bong, and Grand Cape Mount. This shows to us that the traditional people seem stronger than the government and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (which polices traditional societies) is like a toothless bulldog. It barks without teeth.”

Liberian are deserting the traditional societies in droves. In 2007 83% of women reported being members of the Sande Society. In 2020 just 35% did.

But even as the traditional leaders fight to protect their societies the numbers tell a different story.

Liberians have abandoned the traditional societies over the last 15 years. According to Liberia’s Demographic and Health Survey in 2007 83 percent of women surveyed said they were part of the Sande. The survey did not ask about female genital cutting but it was assumed all women who were part of the society were cut.

The 2020 Survey showed just 35 percent of Liberian women said they were members of the Sande.

Experts attribute the plummeting membership of the Sande to widespread awareness campaigns over the last decade that has persuaded women like Dearest’s mother not to do to their daughters what was done to them.

UN agencies have worked hard to help traditional leaders develop other sources of income to replace income derived from the Sande Bush. But it has been difficult to replace the power structures put in place by centuries of tradition, especially in rural Central and Western counties.

“Politicians from rural counties can only get the support of the community unless they adhere to what the traditional people want,” said Johnson. “When the politicians don’t buy into the ideology of the traditional people and when the traditional people rise up against them, they will be bolted out. Politicians don’t have influence over even 25 percent of the voting population.”

Reporting by New Narratives journalists Tetee Gebro, Mae Azango, and Front Page Africa newspaper also opened up the conversation about female genital cutting which had once been taboo because of the fear cultivated by the traditional leaders. Azango was forced into hiding because of threats to her and her 9-year-old daughter when Front Page Africa ran her reporting on female genital cutting on the front page on International Women’s Day in 2012.

In another sign of the traditional societies’ waning influence, reporters today can cover the subject without fear of threats or intimidation.

In the run-up to next year’s general elections, politicians have been treading carefully to try to ensure their victory. Experts say that, even with their diminished influence, the traditional leaders still wield enough power to persuade political leaders to defy the will of international partners and reject the law. But whether it’s illegal or not, the number of girls enduring cutting in Liberia is steadily falling.

Tomorrow, part two of this series reports that traditional leaders have responded to plummeting membership by resorting to kidnapping, extortion, and forced initiation.

This series was a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the Investigating Liberia project. Funding was provided by the US Embassy in Liberia. The funder had no say in the story’s content.