Asokwa Municipality, Ashanti Region – A culture of silence has descended on this industrial area of the Ashanti Region, as residents and health workers say they fear complaining about air pollution that is impacting their health, will lead to repercussions by the government and the institutions they work with.

Residents say the air pollution from a range of industries that operate in the area is making their lives a misery but they have been warned that speaking up may cost them their jobs.

“I am sick. I am very sick. I visited the hospital in 2022. Till date, I have not visited again. The doctor mentioned I am seriously ill. We are ill because of the scent we constantly inhale here at the landfill site. The more we bend to sort out the refuse, the more you inhale it. The scent enters our internal organs”, says a man in his 30s sitting at the Oti Landfill site in Kumasi.

He is a scavenger who makes his living sorting recyclables to sell. He has asked to keep his name secret for reasons that will soon become obvious.

The man is frail and sickly. He wears no protective clothing. He says he is battling coughs, tiredness and shortness of breath. He attributes his poor health to the hazardous gases he inhales all day from the solid waste.

He has little money for medical visits. His last hospital visit revealed he was battling a respiratory infection.

“I take painkillers like paracetamol to ease my pain,” the man says. “Some of my other colleagues are coughing and breathing heavily. I experience headaches sometimes. I also take blood tonic. This has been my go-to drug for years. I am afraid to visit the hospital again.”

Medical practitioners have advised him to switch to a different job. But the man says this is his only choice for a livelihood because he has no formal education.

Scavenging is a source of income for unskilled people in most developing countries. A study by the Journal of Environmental and Public Health in South Africa found health complaints, including respiratory infections, headache, diarrhea, and shortness of breath are caused by polluting gases like methane, and carbon dioxide.

But the true extent of problems at Oti landfill is impossible to assess. In every step of our investigation management and workers have refused to comment.

The Oti landfill facility is one of the country’s largest disposal sites, receiving about 1,500 metric tonnes of garbage every day from Kumasi and its environs. Its location in the community has provided informal jobs for residents, from garbage collection and scrap dealing to scavenging.

We tried to talk with other scavengers at the Oti landfill site but management of the facility refused us entry. Informal workers inside the facility refused interviews saying they feared being targeted by the company.

But those who did agree to speak off camera revealed headaches and migraines are common.

Kwame Lucky agreed to speak on camera. He has pitched camp close to the landfill site. After receiving garbage from the dump site, he airs it for 3 days to reduce the odor before sorting out scraps.

“It is true,” Lucky says. “If the waste comes straight from the dumpsite, you cannot stand the smell. You can see I have piled waste up there. I am doing it so air can pass through and the stench will reduce. After three days or a week, the smell will go down. Afterward, I will bring it to the selection room and begin sorting.”

Management of the landfill knows about the problems. Two years ago, the site was redesigned to reduce environmental damage and eliminate hazards that the garbage was bringing to the community.

But residents of neighboring communities of Dompoase and Oti say the overwhelming smell from the site and their continued poor health shows more needs to be done.

Former assembly member of the Municipality, Elliot Bannor Fosu Jnr. agrees.

“The air pollution depends on the area,” says Fosu. “Especially during the rainy seasons, because of the location of the landfill site, and the bad nature of our roads, the air that comes from the land fill site into the communities is very bad. I must say we do not breathe good air at all.”

Health care facilities in the area, including The Lady Julia Health Centre, Kumasi South Hospital and other clinics refused to comment on the incidence of air pollution related illnesses in the municipality. But some staff who asked for anonymity told Luv Fm they were afraid of being politically targeted for talking to a journalist.

Former assembly member Fosu claims that healthcare facilities in the area record high cases of respiratory infections.

“It is having a health effect on the residents,” Fosu says. “There’s a community clinic here. I initiated it as an assembly member. That is the Lady Julia Health Centre. The residents visit there with breathing problems as a result of poor air.”

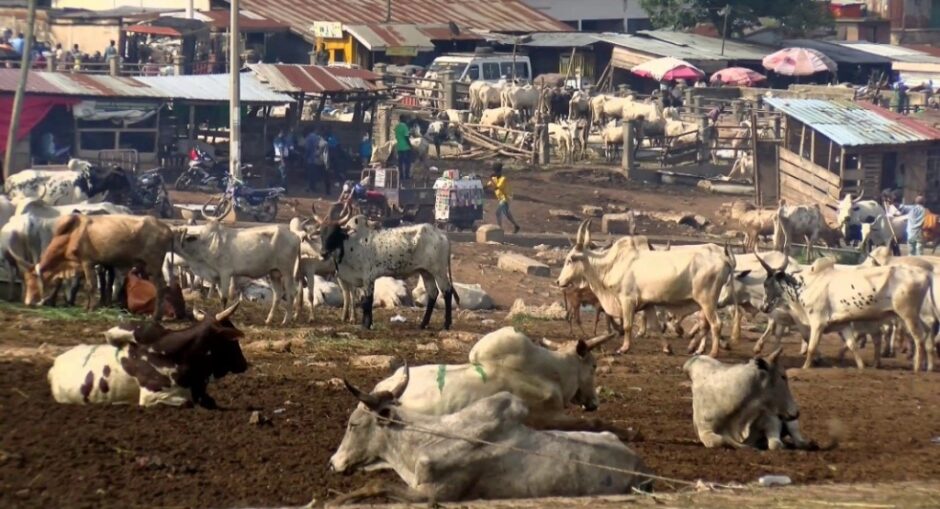

It’s not just the waste dump that is causing air pollution here. On a typical day in the Asokwa Municipality a haze hangs in the air. The municipality is the industrial hub of the Ashanti Region with oil, wood and food processing companies situated alongside the Kumasi Abattoir.

Before 2020, meat was often singed over car tyres and wood. Butchers prepared animal carcasses by burning the furs in open fires, producing thick black smoke. Butchers reported high rates of respiratory infections.

In 2019, then Sanitation Minister, Cecelia Abena Dapaah, banned the practice, to stop the harmful effects on the health of consumers and residents. Butchers have switched to the use of Liquified Petroleum Gas to singe the furs.

“When we were using tyres for the singeing, we were always looking dirty and sick,” says one of the butchers here. “If you saw us, we looked very black. We were getting sick very often.”

Measurement of air quality in Asokwa

While government would not release details of air pollution in the area a group of scientists and other experts measured the air in October 2023 as part of the Clean Air Summer School, held in collaboration between the University of Leeds, in the U.K. and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

Air sensors mounted at the Oti landfill Site and the Kumasi Abattoir measured air quality over several days. At the landfill the site, air pollution exceeded the World Health Organization’s guidelines for what’s known as PM2.5 – the most dangerous air particles – all day, every day. It also exceeded Ghana’s less stringent guidelines for several hours every day.

At the abattoir the sensors indicated the air was unhealthy or unhealthy for sensitive people for a third of the day.

These high levels of air pollution are harming the health of residents according to Medical Coordinator for Doctors in Business Organizations and Public Health Consultant, Dr. Florence Boa-Amponsem.

“We have a lot of these gases that are emitted in the air,” says Boa-Amponsem. “It comes with a lot of effects. There can be cases of upper respiratory issues, breathing problems, coughing, irritation among others. We also have cardiovascular diseases, certain types of cancers, blurred vision and skin irritations. For some gases because of how toxic they are, they can cause skin cancer.”

The research team presented these findings to management of both the landfill site and the Kumasi Abattoir in October 2023. A month later Michael Tongban, production manager of the Kumasi Abattoir, denied the research team recorded high levels of air pollution at his facility.

“Some people came from KNUST to conduct research here on-air pollution,” Tongban said. “It was not as bad as you are talking about. This place is part of the industrial area. We are not isolated. There are industries all over here. So, air pollution is very minimal here. It is an industrial area, so there will be an element of pollution. At first, we were not using good materials for the singeing. Those were used by the local folks. We have been able to sack them all from this place. Now, we are using LPG which does not produce smoke that can pollute the environment. Right now, pollution is minimal.”

Management of the Oti landfill site refused to speak on the findings.

In an interview Faustina Osei Mensah, Municipal Health Director, conceded that respiratory infections are second on the list of health issues recorded in the area. But she downplayed the threat from industry. Instead, she blamed cars.

“This area being an industrial area, we have a lot of cars moving in and out,” Mensah said. “The whole place is choked with human and vehicular traffic. Fumes from the engine of cars are spreading all over. They are all giving us infections.

“We visit the factories and advise them concerning the burning of their waste. So, for that one we know it is under control. We have a lot of factories here. If they should do open burning, it will affect all the residents here. We have instructed all of them to get chimneys so that the pollution will be reduced.”

But now the municipality has been found to have high levels of air pollution, Mr. Mensah says and adds that the government is embarking on sensitization programs to combat human activities which contribute to air pollution.

In the meantime, Dr. Boa-Amponsem advises workers and residents in light industrial areas like the Asokwa Municipality to protect themselves.

“Most of the time people who are working in these industries are in protective garments,” she says. “But I am going as far as people who live closer. Sometimes, they feel they do not necessarily have to be protected. But they are the ones inhaling the gases. I would advise people who live close to industries to constantly wear nose masks.”

This story was a collaboration between Joy Online and New Narratives with funding from the Clean Air Fund. The funder had no say in the story’s content.