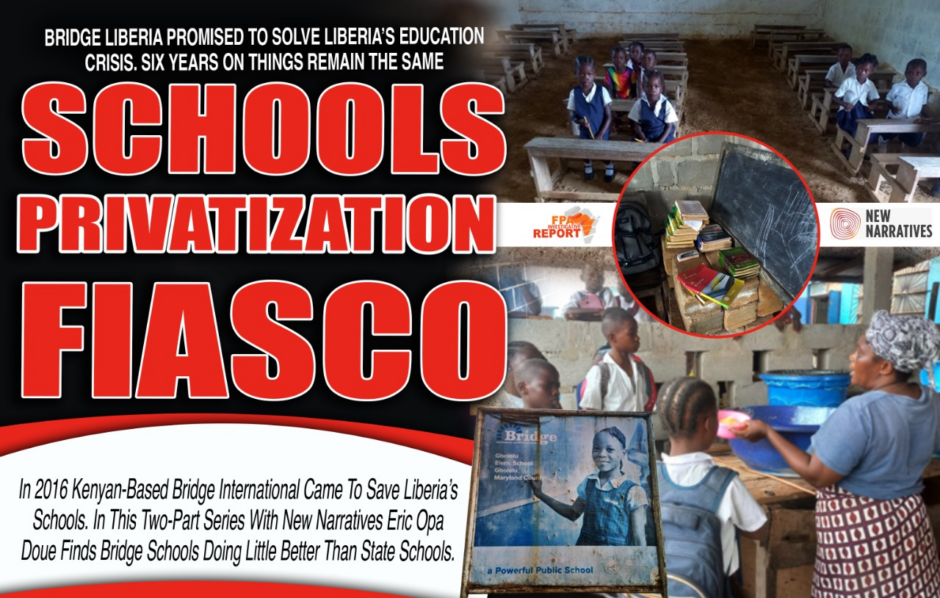

In 2016 US-based Bridge International Came To Save Liberia’s Schools. In the first of a two-part investigation with New Narratives Eric Opa Doue finds Bridge schools doing little better than state schools.

YARPAH TOWN, River Cess County – Babygirl Smith helps her mother to sell snacks at the town market every Monday. The 17-year-old should be in grade 11 at the local school but she was stopped from attending in 2016 when Bridge International, the Kenya for-profit company, took over. Now school is out of the question. Babygirl has her own baby to look after.

Babygirl’s father Emmanuel says that when Bridge took over the Togar Macintosh School that Babygirl and her three siblings were attending, parents were told to choose two of their children to enroll. Bridge was providing uniforms and they only had enough for two from each family. Smith felt he had no choice but to stop Babygirl and a younger son from going to school. It was a choice that still pains him.

“They say they came to help us, but I don’t think so,” Smith says. “You can’t say you helping people and you allow their children drop from school because of restriction.”

Togar Macintosh was one of the first 23 schools taken over by Bridge as part of a radical experiment by the outgoing Sirleaf administration. Reeling from Ebola and still dealing with the legacies of the civil war, the education system was failing by every measure. Only 38 percent of kids were enrolled in school. Among adult women who had finished primary school, only one-quarter could read a sentence.

Bridge was one of eight private providers invited to take over 93 randomly-selected public schools – 8.6% of all public school students – in what would eventually be named “Liberian Education Advancement Program” or LEAP. Chosen providers included for-profits and non-profit charities; local and international organizations. After the program issued a self-report claiming the schools had achieved significant gains (despite independent reports finding marginal improvements) the Weah Administration increased the number of schools in the overall program to 487.

Four of the eight providers dropped in the next few years because they could not raise enough funds to continue. One of them, More Than Me, was taken over by Hill Top after a Time magazine investigation revealed that the inexperienced American head of the organization had put a pedophile in charge.

Among the four organizations left, Bridge now manages the vast majority. After starting with 23 schools in 2016 Bridge now manages about 75 percent – or 360 – of all the LEAP schools.

When it came to Liberia Bridge was already a controversial chain of for-profit schools, based in the United States but working in Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and India. It relied heavily on technology and scripted lessons. It was backed by Silicon Valley investors such as Bill Gates and Facebook. Its ambition was to education 10 million poor children by 2025. By 2018 it had raised $100 million from investors and was losing about $12 million a year.

In 2015 when Jim Yong Kim, then-president of the World Bank, announced a major investment in Bridge he sparked a global backlash. Organizations such as ActionAid and Education International(EI), which claims to be the world’s largest federation of teacher unions and associations, expressed deep concern and called on the Bank to support free universal education instead. Studies commissioned by EI identified many issues in Bridge schools including substandard teaching methods and facilities and practices aiming to make profit at the expense of educational outcomes.

Bridge met resistance in Liberia from day one. Critics pointed out that the heavy focus on tablet computers with lessons scripted by academics 7,000 miles away was impractical when most of Liberia which had little access to internet or electricity.

A 2020 report by Center for Global Development, a global think tank, looked at the learning gains, access, safety and sustainability of the project in Liberia over a three-year period and found mixed results. Children were reading roughly 2.2 additional words per minute. But dropout rates had increased by more than half and fewer children were moving to secondary school. It also found Bridge failed to reduce sexual abuse. A failure to raise funds was a major factor. In the first-year expenditure per pupil was $US640. By year three that had dropped to $US161. But that was still nearly three times what other LEAP schools or state-run schools were spending.

The report found “any assessment of outsourcing public schools to Bridge must weigh its modest learning gains against its high operating costs and negative effects on access to education via increased dropout.”

That mirrors the experience of students at Togar Macintosh. New Narratives/FPA visited the school’s campus in September – a week after the opening of schools across the country. About 90 students had registered and more were expected. Active learning had not started. Some kids were playing around the school grounds– there were no teachers to teach them.

The building was in a deplorable state. There were no ceilings or doors in classrooms. The floors were bare dirt. Some kids were seated on the floor because the few old desks were not enough. Teachers sprinkled water on the floor to prevent dust.

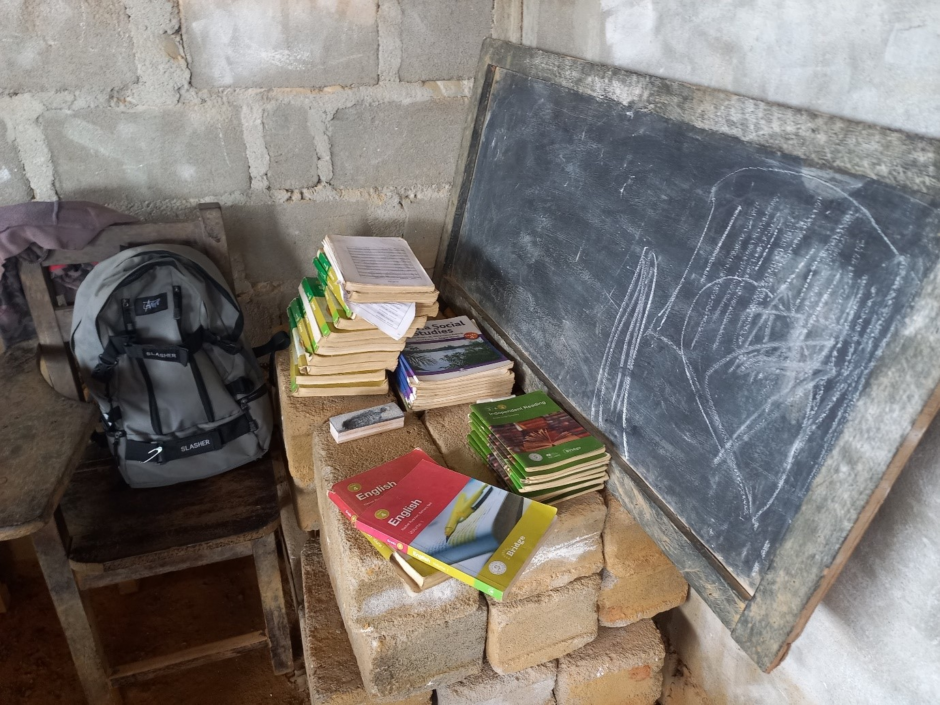

Five of eleven assigned teachers laid down their chalk in 2021 demanding salaries they say government owes them. The school is now being run by the vice principal for administration and four teachers. Bridge is yet to supply the school with learning materials. They are using materials from the last two academic years.

Teacher training and learning materials were Bridge’s responsibility under the agreement between government and Bridge. Upkeep of the school buildings and payment of teachers fell to government. At Togar Macintosh neither side is meeting their side of the deal.

The academic outcomes are poor. No children at Togar Macintosh sat the 2022 WAEC exams. Parents and teachers here are asking how this Bridge school which promised so much and for which some of their children’s educations were sacrificed, is any better than government-run schools?

“The children, their learning is not really going on the way it supposed to be because the classes here are self-contained, so, because of no teachers we combined some of the classes and more especially it will affect the children this academic year,” says Vice Principal Moses Gbah.

It is not just Togar Macintosh. NN/FPA’s recent visits to other Bridge schools in River Cess and in Grand Bassa County, Lofa County and rural Montserrado found Bridge facilities in these counties were also very poor. Everywhere there were old desks in the classrooms with hanging ceilings due to leakages. Teachers and learning materials are missing.

At Sarah Sampson George, a Bridge school in Buchanan, Grand Bassa County, teachers say they haven’t received learning materials. They complain about overtime pay they say Bridge owes them. Some teachers have quit.

Principal Emmanuel Wadagbo says the Parents Teachers Association has been working to get some desks and as well as repair the damaged ceilings. For him, there is no need for government to continue with the agreement it has with Bridge.

“What Government needs to do is to get some of the system that Bridge has,” says Wadagbo. “Government paying her teachers, Bridge is not paying them. Teachers going extra mile, no incentives. Nothing is different, so what the essence? So, government should take over and we all revitalize our education system.”

In part two of this two-part series Bridge and the National Teacher’s Association respond to the investigation’s findings.

This story was a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the Investigating Liberia program. Funding was provided by the Swedish Embassy in Liberia. The funder had no say in the story’s content.