Monrovia – In separate chilly mornings in September and October 2021 Sarah and Kolu defied the weather to travel to Roberts International Airport with one thing in mind: a trip to “paradise,” where all their sufferings and hardship would end.

The pair, cousins in their 20s whose names FPA/NN is concealing for their security, say they scratched and borrowed the payment demanded by local recruiter Cephus Selebay to get their visas, passports, and the tickets to their dreams. Sarah claims she gave Selebay $US350 for her travel documents. Kolu says she gave him $US450.

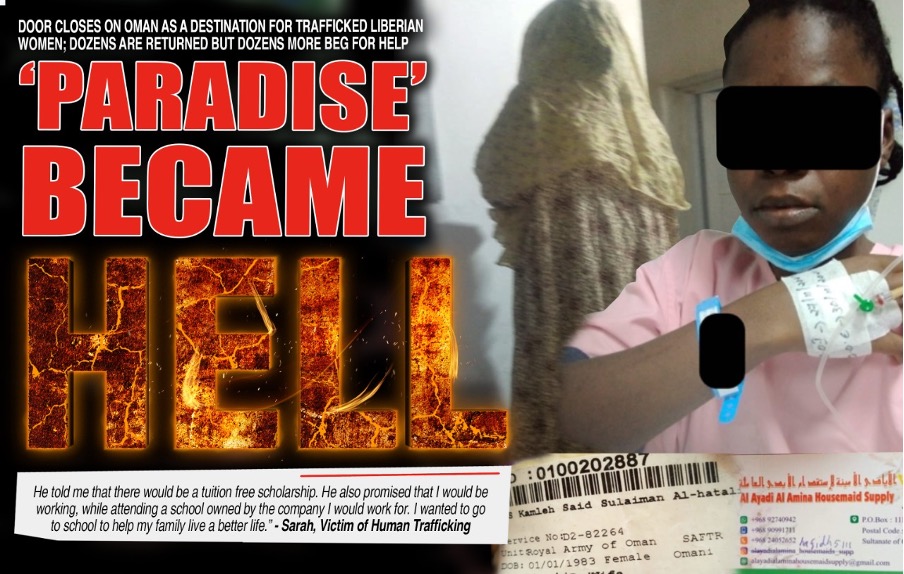

“He told me that there would be a tuition free scholarship,” says Sarah. “He also promised that I would be working, while attending a school owned by the company I would work for. I wanted to go to school to help my family live a better life.”

The women didn’t tell their families they were going. The cousins didn’t even tell each other. Each believed that telling anyone would break their “luck” and they would be grounded in Liberia forever.

Sarah and Kolu’s dreams faded the moment they landed in Oman, the poorest of the Arabian Peninsula oil states that border the Persian Gulf. The women say the Omani agents, one named Chris Ali, grabbed them immediately at the Muscat Airport. The women had been ordered not to change clothes during their journeys. Selebay had sent photos of them at the Liberian airport so the Omanis could identify them by their clothes. The Omani “masters” were from an agency that brings low-cost domestic workers to the kingdom. A business card obtained by the women named the agency as Al Ayadi Al Amina Housemaid Supply.

Sarah and Kolu say their passports and travel documents were seized by the agents. They men took them to an office filled with women from Africa and Asia. The realization that they had been deceived quickly began to sink in. Omani clients came to inspect them in a scene the women describe as being like a slave market: Africans together in one spot, Filipinos, Bangladeshis, and others together. The women were soon “bought” and taken to houses to begin their time as domestic servants.

What the women didn’t know was that as many as 200 Liberian would make that same journey over coming months. They were some of millions of men and women from African and Asian countries lured by recruiters to work in the Middle East according to the 2022 United States Trafficking in Persons report. The nearby state of Qatar has been the focus of attention during the World Cup. A Guardian investigation estimated the country had lured as many two million workers from the Philippines and South Asia to construct the $300 billion city and eight stadiums needed for the Cup. The Guardian estimates thousands died in sweltering heat and filthy living conditions during the ten years of breakneck-speed construction. Qatar admits to just 40.

Most are recruited under the “kafala” system, a legal employment system used throughout the Middle East where “sponsors” pay for foreign workers travel and accommodation in return for low pay. Workers are routinely misled. And have few rights or recourse to leave. Qatar says it has ended the system.

Women living in extreme poverty have been lured to Middle East nations to serve as domestic servants under the system for decades. According to the administration of then President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, five dozen Liberian women were trafficked to Lebanon between 2011 and 2012. Almost all are deceived about the true nature of their work. Experts say this is when a legitimate labor arrangement becomes trafficking. All the women FPA/New Narratives interviewed for this investigation say they were misled. They say they were paid less than agreed and worked as long as 12-hour days, 6 or 7 days a week.

During this investigation FPA/New Narratives met women who tolerated the conditions in Lebanon simply because it was preferable to starving in Liberia, but for the majority of women the conditions are intolerable. They often involve beatings, starvation, sexual assault and, in some cases, death. That has been the case for many of the estimated 200 women like Sarah and Kolu who went to Oman.

“I took care of a family of seven,” said Sarah. Omani society and law are based on Sharia law. Women’s rights are curtailed, and women must dress “modestly” in long dresses and head coverings. “There were ten bedrooms, five bathrooms and four living rooms. I did any domestic work you could think about. I woke up 4AM and went to bed at midnight.”

Sarah’s “sponsor” was the mother of the household, a woman named Kamleh Said Sulaiman Al-hatali. A hospital band that Sarah would later receive showed that the sponsor’s husband was a member of the Royal Army of Oman.

Kolu says she worked in a family with 19 members. She likens her condition to “hell” and says they were treated like “slaves”. “When I woke up in the morning, there was no stop of work,” says Kolu. “I had to wake up 4AM and go to bed at midnight. No resting. No day off.”

Kolu says she was not given enough food to eat. There was no African food and local food made her sick. “When they cooked, they ate and gave us the left over,” says Kolu. “I was made to drink dirty water from the faucet of the kitchen. That affected my stomach and made me seriously sick.”

Both women say they were beaten and treated as sub-human. For Sarah only the mother of the house spoke English. The rest didn’t speak to her except in Arabic terms of abuse. The women were uncomfortable talking about young men in the houses but said they were given free rein to torment them. They say they knew of other women who were routinely sexually abused.

Both women told their sponsor and agent that this was not what they agreed to and wanted to leave. But the sponsors had paid the agent $US1,500 plus return airfare to have the worker for a two-year contract. If Sarah and Kolu wanted to leave, that debt must be repaid. Only then would their passports be returned.

That is where things end for most women according to Ward Reddick, a Canadian who has been working to repatriate Africans trafficked to the Middle East for a decade and now works with the Rain Collective, an anti-trafficking organization. The agent will offer the sponsor a refund if a woman leaves in the first six months. But no one wants to be left out of pocket. The agent will pressure the women to stay, go to another house of get her family to pay. Most women are forced to stay. But Liberians presented a problem for the Omani agents.

“One of the things that’s been odd about this Liberian group of women is that they all know each other,” says Reddick. “They were all in this Whatsapp group. And they got organized.”

Sarah was one of the first to escape her house. She had been taken for surgery against her will and was terrified her sponsor was trying to take a kidney. (Doctors in Liberia said it was minor exploratory surgery likely to investigate the cause of Sarah’s abdominal pain.) She contacted Kolu who also escaped. They reached their families in Liberia who contacted media. The Liberian government became involved. More and more women handed in their resignations. They filled up a safe house.

The women found Reddick and his network in Oman who went on to work with Liberian and Omani authorities to release the women from their contracts and return their passports. A Liberian consular official in Dubai named Samuele Landi became “a hero” according to Reddick. Some of the women’s families eventually found the money. The Liberian consulate did not respond to requests for comment, but a source inside the consulate, who spoke on condition of anonymity on grounds that they were not authorized to speak publicly, said the debts were not paid by the Liberian or Omani governments. FPA/NN has gathered that in many cases the government paid for the flights home. 125 women have returned home since March according to the Liberian Anti-Trafficking Unit.

Sarah and Kolu are now living in Monrovia, scratching to get by as they were before they left for Oman, only now they also owe debts to family. They told their stories to news media hoping to deter other women from going. But even as they did other women were scraping together funds, lying to their families and boarding planes for a “better life” in Oman.

Part two of this series will look at efforts to find the women remaining in Oman and failed efforts to prosecute the Liberian mastermind of the trafficking ring.

This series is a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the Investigating Liberia project. Funding was provided by the US Embassy in Liberia. The funder had no say in the story’s content.