Pleebo, Maryland County – The 14-year civil war spared no part of Liberia. The county of Maryland suffered an especially heavy toll. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report recorded 3,934 victims here, the second highest after Sinoe (5,706).

This story first appeared on FrontPageAfricaOnline as part of a collaboration for the West Africa Justice Reporting Project.

Some of the events included the October 1994 killing of 24 people by the National Patriotic Front of Liberia, accused of being supporters of the rival Liberia Peace Council. Simon Gyekye, a Ghanaian schoolmaster in Pleebo, was among those killed. The LPC killed Samuel Kawah, former Superintendent of Maryland in 1996. John Hilary Tubman, a prominent businessman in the county, was killed in 1994.

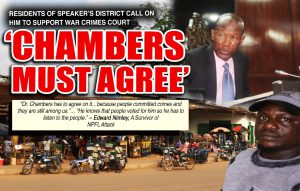

In dozens of interviews with local residents here in Pleebo it is clear that there is strong support in Maryland for the growing national call for justice through a war crimes court. That may put the people out of sync with their Legislative representative, Bhopal Chambers, the powerful house speaker who opposes a court. It may also create a challenge for Chambers when he seeks a third term in 2023.

Dr. Chambers voiced his opposition to the court at an August 2018 session of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) saying he preferred “restorative” justice, instead of “retributive” justice. Restorative justice brings resolution through reconciliation between the accused and their victims, while retributive justice punishes criminals for wrongdoing.

Many of the people FrontPageAfrica interviewed in Pleebo called on the speaker to change his position.

“Those that committed atrocities against the Liberian people need to be punished,” said Daniel Morsor, 35, a resident of Pleebo. “That is the only way the wounds [will be healed] and the souls of those who lost their lives will rest in peace. We don’t even want to see them holding government position in this country.”

“If they don’t bring them to the war crimes court, for this country to develop will be very hard,” said William Bono, a 47-year-old businessman.

“If we set up a war crimes court in Liberia it will send a kind of a warning to those who in the future will intend to do similar thing,” added Alex Summerville, 46.

Summerville, Bono and Morsor said they all voted for Speaker Chambers in the 2017 representative elections for the Maryland County Electoral District 2.

Maryland is a stronghold of Speaker Chambers’ party, the ruling Coalition for Democratic Change of President George Manneh. Weah won 81.3 percent of the presidential runoff votes there in the 2017. Speaker Chambers won 57.3 percent in a 10-man race to retain a seat he has held since 2006.

“Dr. Chambers has to agree on it…because people committed crimes and they are still among us,” said Edward Nimely, an inspector with the Pleebo General Market. “He knows that people voted for him so he has to listen to the people,” Nimely, 41, who wears a scar on his buttocks from an NPFL attack here in 1995 that killed two of his brothers.

“We appeal to him to see reason to make sure to enforce it so that this war crimes court can be set up in Liberia,” said Morsor.

The government of Liberia is under immense pressure locally and internationally to implement the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which include the establishment of a war and economic crimes court. The United Nations Human Rights Committee has given the country up to July 2020 to implement a process for seeking justice. In May the House of Representatives received a petition from local advocates to establish the court. And the House of Representatives of the United States of America passed a resolution in November to support the full implementation of the TRC report.

Debate on the Court

Like in Monrovia and other parts of the country, the debate on the court ensues.

There were more voices against the establishment of the court than those in favor at a well-organized debate at the Pleebo Intellectual Forum in the heart of the rapidly urbanizing town with the newly paved road connecting Fishtown, River Gee to Harper, Maryland.

Thirty-five-year-old Mustapha Jalloh voiced the suspicion of many in the room that the push for a court did not come until the new government of George Weah was elected.

“During the regime of former President Ellen Johnson Sierleaf they did not talk about it,” Jalloh told the well-attended forum at a makeshift shop. “They talked about reconciliation, but after this government came in then they brought this war crimes court to start disturbing the development of the Pro-Poor Agenda [for Development and Prosperity].”

“I think what Liberia should be thinking of is development, getting road from Ganta, [Nimba] to Maryland County,” said Dio Williams, 24.“Setting up a war crimes court will not help us. Even today we have Charles Taylor in The Hague. What better is that doing for Liberia? If we carry Prince Johnson—who is the godfather of Nimba County—what good will it do for Liberia?” Williams asked.

Gripman Saytue, an opponent to Speaker Chambers in the 2017 election, charged that the court was a ploy by the international community to undermine the progress he said Liberia was making.

“Liberians who are pushing for the coming of the war crimes court forget to know the genesis of our war,” charged Saytue who finished third to Speaker Chambers with 7.2 percent of the votes. “If they actually got the genesis of our war, they will not be calling for war crimes court. They should go after those who brought those who brought the war on us.

Supporters of the court also made themselves heard.

“This is a war crimes court that is going to address the legacy of [the civil war] of our country,” countered Abel Teewon, 25, a resident of Harper, who voted for the CDC. “The legacy of the Liberian civil war will be brought back to the spotlight and will be investigated fully and people will know exactly what happened and learn from their mistakes.”

Teewon said that not prosecuting warlords set a bad precedent for future leaders and responded to the justice-development point made by the other side of the debate.

“Justice is not against development,” he said. “If justice was against development, then what do you make of the presence of the Supreme Court of Liberia and people are building roads?”

‘…In God’s Hand

In the Pleebo Market community support for the court was overwhelming.

Alfred Nyumah, a 67-year-old nurse, said there was nothing wrong in prosecuting those who bear the greatest responsibility of crimes that were committed during the civil war.

Others like Tom Cooper, 38, who lost two uncles to an LPC attack in 1995 and the 2003 invasion of the Movement for Democracy and Development (MODEL), sit on the fence.

“I leave all matters into God’s hand. I don’t know who killed them…but I want God be the judge.”