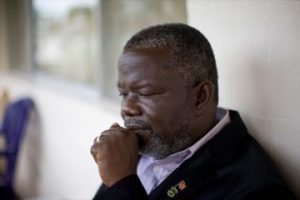

Surrounded by bodyguards, Prince Yormie Johnson swaggers with confidence toward a meeting hut in the center of his large Monrovia compound, decorated with brass figurines and farm animals.

The Liberian senator and former warlord is among the 16 candidates vying for the presidency in the Oct. 11 general elections.

Johnson, 52, already behaves like a ruler. He sits regally in the center of the palaver hut, filled with dozens of followers and some of his 12 children. In a dark African shirt and a red hat, he outlines the reasons he is running for president.

“We want to see real peace, and to have real peace we got to have genuine people at the head of leadership in this country, straightforward people,” said Johnson, who took part in the torture and killing of then President Samuel K. Doe. Johnson has also been accused of being responsible for the deaths of thousands of other Liberians during the country’s civil war, which lasted from 1989 until 2003 and then again from 2006 until 2009.

Johnson is a thorn in the heel of incumbent President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf because of his popularity in his home area, voter-rich Nimba County. During the campaign, he has urged Liberians to stockpile food and water ahead of the elections, convincing some that he has not completely turned his back on violence.

An acolyte of former rebel leader-turned-president Charles Taylor, Johnson broke away from Taylor during the siege of Nimba by neighboring Ivory Coast in December 1989. In Monrovia, he established his base in Caldwell, Bushrod Island, which he controlled until the arrival of ECOMOG soldiers in August 1990.

One month later he presided over the gruesome torture and killing of then President Doe. Doe’s ears were sliced off and he was left to bleed to death. A home video captures Johnson in fatigues, swigging Budweiser beer as he orders Doe’s torture.

After Doe’s death, Johnson spent 14 years in Nigeria in self-imposed exile, working as a preacher. He returned to Liberia in 2005 to run for the senate. While in Nigeria, Johnson expressed regret over his role in the civil war. In a July 2003 interview with the South African newspaper, The Sunday Times, Johnson said, “I am sorry I murdered the former President. I must be very frank, I regret it. I thought that the death of Doe would bring peace but it never brought peace.”

The son of a Gio hunter, Johnson was born in Tapeta in Nimba County but raised and educated in Monrovia. He joined the Armed Forces of Liberia in the early 1970’s and quickly rose through the ranks as a military policeman and intelligence officer ultimately earning the rank of captain.

While he now commands respect as a senior lawmaker, a cross section of Liberians still remember him as a brutal military man.

Madam Oretha Flome, who sells coal in Monrovia, says she observed Johnson in 1990, when she sought refuge at his Caldwell base.

“Prince Johnson is not a sound person, because the blood of innocent people is on his head,” said Flome. “The only way he would become president is when those he killed can come back to life and vote for him, but it won’t be sensible people like me would vote for him. One day Johnson shot a man and asked people around to advise the dead body not to repeat the same mistake that lead to his death.”

Alvin Boto recalls, “On his base during the war, he killed a Liberian singer called Teconso Roberts and asked for him the next day.”

But there are plenty of Liberians who say Johnson should not be blamed for his actions in the war.

“Liberians should know that it was war and many things done are left in the past because the meaning of war is ‘waive all rights.’ We should forge ahead and stop blaming Liberia’s incoming President Prince Johnson,” said James Mentee, a street vendor who sells cosmetics.

Johnson is not likely to win the presidency, but he could be a spoiler for Johnson Sirleaf, said Dan Saryee, the head of the Liberia Democratic Institute.

“He is a stakeholder in this process. For various reasons … he has some level of influence because people still feel disgruntled due to unemployment. They feel that he could serve as a rescue,” Saryee said.

Johnson’s campaign has been characterized by uncertainty. He was not seen in the country for several months, during which time it was said he was recovering from a stroke in Nigeria. He denies that was been ill.

Johnson caused a media storm in August when he accused the president of trying to kill him when one of his party members was struck by a vehicle in the president’s convoy.

Johnson says he once viewed Johnson Sirleaf as a friend and ally, but he’s now a fervent critic of the corruption that dogs her government.

“Other regimes were fought bitterly because of what we term as a corrupt system: unaccountability, non-transparency, lack of the rule of law that led to the dethronement of many regimes, like Tolbert,” said Johnson to GlobalPost. “The very Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and us charged those governments for corruption, rampant corruption and what have you. Today she is the president of this country and she is not bringing new reforms.”

Johnson has also called the president “the mother of war” for her financial support of Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia in 1989. Johnson Sirleaf subsequently condemned Taylor. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission report recommended both candidates be banned from seeking public office for 30 years.

Nevertheless, he says that if he does not win Liberia’s presidency, he won’t destabilize the country as people fear. Instead, Johnson said he’ll build a 600-person cathedral and retire.