Monrovia – Running a war crimes court is an expensive exercise no matter where it is held. From construction of court buildings and detention facilities to salaries of judges, lawyers and administrators, to security and witness protection, costs add up quickly.

For the officials drawing up plans for Liberia’s war and economics crimes courts, the question of funds is likely the most vexing. They may draw up the most perfect plans for a court but at the end of the day, much will be dictated on how much they have to spend.

Early in the process, some officials had raised numbers on a comparable level as the Special Court for Sierra Leone, which spent more than $US300 million ($US430 million in 2024 dollars) in the 10 years to 2013 to convict just 12 people, including former Liberian President Charles Taylor.

But behind the scenes, international donors have told the government that is fanciful.

“I don’t think you will ever find this kind of money,” said Alain Warner, a prosecutor with the Special Court for Sierra Leone and director of Civitas Maxima, which has had a key role in cases in Europe and the United States over the last decade against accused warlords linked to Liberia’s civil wars. “I really do think that it’s completely unrealistic to think that you can find $US100 million, $US200 or $300 million. It happened for the Special Court, but this was a long time ago and I do not think that the U.N. did anything similar since. I do not see where that much money can come from.”

Alain Werner, Director of Civitas Maxima, outside the trial of Liberia’s Kunti Kamara in Paris, France in 2022.

The Special Court for Sierra Leone, resulting from a special agreement between the United Nations and the Sierra Leone government, was groundbreaking in many ways. It was the first court since the second world war to convict a former head of state. It secured the first-ever convictions for attacks against UN peacekeepers, for forced marriage as a crime against humanity, and for the recruitment of children for combat.

But its huge costs and failure to integrate into the country’s legal system drew anger, particularly as the country’s economy was crushed and victims received just $US80 each. Since then, a number of African courts have tried so-called “international crimes” – serious human rights violations including war crimes and crimes against humanity such as rape as a weapon of war and recruitment of child soldiers – for far smaller costs. Behind the scenes, the international donors who will be called upon to fund the courts – European countries, the United States and the UN – are sending the strong message that they will not be providing hundreds of millions of dollars for the courts, particularly when so much government and donor funding is going into corrupt officials’ pockets.

As a coalition of experts get to work on plans for Liberia’s war and economics crimes courts, there are a large range of issues to consider. In a special series Front Page Africa/New Narratives look in depth at the issues. Where will the court be held? How much will it cost and who will pay? What security issues need to be considered? Who and how many people will be tried? In Part 2, we ask how much the courts will cost and who will fund them.

In a recent meeting at the U.N., Beth Van Schaack, U.S. Ambassador for Global Criminal Justice, pointed to so-called “hybrid” courts in the Central African Republic and the Extraordinary African Chambers that tried former Chadian dictator Hissène Habré in Senegal as “right-sized” models for Liberia. Each cost under $US15 million a year to operate.

But while experts agree that a limited budget will be available, they say the challenges faced by Liberia’s courts will be immense. They will likely have to deal with more complex cases than other courts. With a mandate extending from the end of the wars in 2003 back as far as the rice riots in 1979, evidence will likely be more difficult to come by and cases against the worst perpetrators could cover periods of many years.

“Because of its complexity, if we’re talking about a court that deals with these issues from the past to a large extent, it could certainly extend its work over 10 or 20 years, to be frank,” said Ambassador Stephen Rapp, a former chief prosecutor for the Special Court. “But I think certainly it would be very difficult for it to be done for, say, less than $US60 million.”

The funding will also impose limitations on who and how many will be tried. The country’s 2009 Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report recommended 116 “most notorious perpetrators” and eight faction leaders be tried for gross human rights violations and war crimes. Another 58 were recommended to face domestic courts for lesser crimes. It recommended 40 people and companies face trial for economic crimes and another 54 be investigated.

The limited funding available to Liberia will likely mean that far fewer face trial. The Central African Republic trial, for example, has indicted 22 perpetrators and convicted three since it started in 2018 – though its operations were impacted by Covid lockdowns.

Experts say Liberia’s victims will have to get their heads around the fact that a relatively small number of perpetrators will face justice.

The TRC Report recommended the country engage in a widespread restorative justice and accountability mechanism based on the traditional “Palava Hut” process where “members of integrity within the community adjudicate matters of grave concern within the community and seek to resolve disputes among or between individuals or communities.” A National Palava Hut Program has operated in fits and starts over the last 12 years without enough funding to support it. To ensure victims’ support for the courts process, the government may need to reinvigorate the Palava hut process.

One major question early on will be whether to try Charles Taylor, who headed the rebel faction, the National Patriotic Front of Liberia from 1989 until his election as president in 1997. The NPFL committed the largest number of atrocities reported to the TRC. Government troops under Taylor’s 1997-2003 regime committed many more. Security concerns convinced the Sierra Leone Special Court to move Mr. Taylor’s four-year trial to the Hague in the Netherlands, with security and locations costs of as much as $US250 million, according to a former official at the Court. (Mr. Rapp was one of many who thought that was unnecessary.) Mr. Taylor’s legal bill alone – footed by the court – was $US5 million or nearly $US7 million in today’s dollars.

Mr. Taylor is imprisoned in the U.K., with more than 25 years to go on his sentence. U.K. and Special Court authorities would likely have to give permission for him to be moved to face trial in Liberia. The costs involved may dissuade court officials from deciding to prosecute Mr. Taylor. That will raise the question as to whether justice can truly be said to be done in Liberia if Charles Taylor, held by many to be most responsible for the extraordinary horrors suffered by Liberians, is excluded from prosecution.

Tennen Tehoungue, Liberian transitional justice expert

Liberian transitional justice expert, Tennen Tehoungue, has argued for a different approach to find additional funding for the courts. She has urged the government to push international donors to seize funds and assets held in their countries by those accused of profiting from the war. Among those listed on the TRC Report is Benoni Urey, a maritime chief in Taylor’s government; Taylor himself; Oscar Cooper, an ex-senator; Emmanuel Shaw, an economic advisor to former presidents Samuel Doe and George Weah; Senator Edwin Snowe of Bomi County; Roland Massaquoi, an ex-Agriculture Minister in Taylor’s Government; Nathaniel Barnes, an ex-Finance Minister in the Taylor government and Lewis Brown, Taylor’s last national security advisor.

She said this move would free the government from depending on the international partners for donations and promote Liberian ownership of the courts.

“That goes to the question of ownership of the process; the Liberian government showing that it is owning this process by taking these kinds of steps, instead of relying on donors or friendly nations to provide it,” Madam Tehoungue said. “They must be asking instead to know whether banks have money, allegedly, taken from Liberia, that are stored in those accounts in those countries.”

Mr. Aaron Weah, another Liberian justice scholar, said that would involve an investigation by an inter-governmental team comprising Liberia’s Financial Intelligence Unity and their counterparts in other countries to establish “the veracity of the allegations”. But her worries it would take too long.

“We have institutions in place that can bring some credibility to this information,” said Weah by a WhatsApp call. “Other than that, it is for now very speculative.”

Donors and Liberian activists expect the government to make a significant contribution to the costs in order to show it is seriously committed to the process.

The Liberian government had initially allocated $US500,000 to the Office for the Courts in the 2024 national budget. It’s unclear how much was allocated in the recast budget, approved overnight by the Legislature. The budget isn’t yet publicly available.

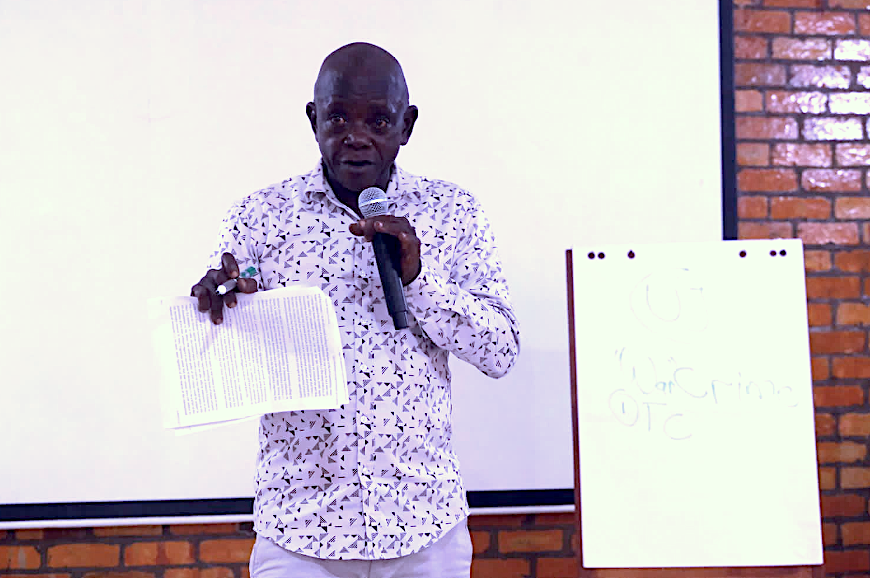

Mr. Hassan Bility lectures journalists about transitional justice. Credit: Ricardo Partida/New Narratives.

Mr. Hassan Bility, Director of the Global Justice and Research Project, which has worked with Werner’s Civitas Maxima to prosecute individuals overseas for war-related crimes in Liberia, said the government must stump up a sizeable amount of money now.

“I do not believe that the West is going to want to start providing fundings if they do not see concrete actions taken by the government,” said Mr. Bility. “I believe the Liberian government should be the first to set the example for other countries to follow. Come out with $US5 million. Come out with $US2.5 million. Come out with $US1 million, come out with $US800,000. The government needs to set the pace by taking more concrete actions.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Bility has suggested another way to find the funds: cutting the salaries of sitting legislators and government officials who have been accused of war crimes. Liberian lawmakers’ salaries are among the highest in the world.

“Why should we pay somebody a ridiculous amount of money and you get 10, 20 young people who are doing drugs because some of these people being paid this money; their actions led to the wars?” he asked. “Why can’t you support the court? Government’s work has been made so attractive at the expense of the Liberian people – the taxpayers – everybody is running there.”

The next stories in this series will look at issues including who could be tried, security, staffing, location and witness protection for the courts. This story is a collaboration with FrontPage Africa as part of the West Africa Justice Reporting Project. Funding was provided by the Swedish embassy in Liberia. The funder had no say in the story’s content.