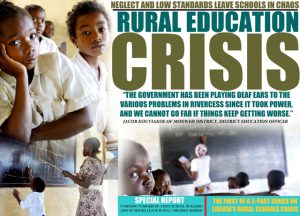

Cestos City – Students in Rivercess County are learning less than half of the curriculum each semester because of untrained teachers and a broken pay system that forces teachers to abandon schools for days, even weeks at a time.

Cestos City – Students in Rivercess County are learning less than half of the curriculum each semester because of untrained teachers and a broken pay system that forces teachers to abandon schools for days, even weeks at a time.

The first of a 3-part series on Liberia’s rural schools crisis by New Narratives fellow Mae Azango. Photos by New Narratives fellow Chase Walker. Originally published in FrontPage Africa here.

A FrontPage Africa investigation, in collaboration with New Narratives, has found students here are losing out because of major disruptions and low teaching standards. Experts say the situation in Rivercess is likely being repeated across the country in an education system that, a decade after the war, remains in chaos.

Teachers in outlying areas of the county must leave their classrooms to walk for many miles, or use their own money to cover the county’s one main bumpy, dirt road by motorbike, in order to get to the capital seat of Cestos City. This is the only place where they can collect their salary. The roundtrip can take as long as two weeks, meaning their classrooms may sit empty for half of each month, according to school and district officials here.

When teachers are away chasing their salaries, they are unable to complete the lesson plans and students fall behind, said Matthew Swary, district education officer (DEO) for central Rivercess.

“Due to the slow payment scheme, students in Rivercess are only able to cover 35 percent of the full curriculum, which is bad, but what can we do?” said Swary, who as DEO is responsible for monitoring schools in his district and reporting to the county education officer.

Located in the south-central part of Liberia, Rivercess County has a population of 71,500 and a large number of Liberia’s poorest people, many of whom are uneducated and unemployed.

The payment problem within the educational system is an age-old national issue, acknowledged Mator Kpangbai, who was Deputy Education Minister for Instruction from 2010 to March 2013.

The payment problem within the educational system is an age-old national issue, acknowledged Mator Kpangbai, who was Deputy Education Minister for Instruction from 2010 to March 2013.

“This is not limited to Rivercess alone but the entire country because all of our teachers are going to some capital to get their pay,” said Kpangbai after FPA/New Narratives journalists visited Rivercess last year.

Under the current payment scheme, the finance ministry’s pay team visits central points and capital cities of each county in the country once a month with funds to pay teachers.

Rivercess County Junior Senator Dallas Gueh, said teachers complain that the pay team only stays for a few hours paying some and then leaving a long line of angry teachers who must then chase their salaries all the way to Monrovia.

“Then we sit and say the future is for the young people when we are not preparing them for the future,” said Gueh. “Government will have to decentralize the payment of teachers, because teachers leaving the classroom to run behind salary is harming students greatly.”

When the current centralized payment system fails, teachers routinely storm the Ministries of Education and Finance in Monrovia in search of the money owed them.

Last October, 300 out of the total of 900 teachers from leeward counties accused the government of removing their names from the payroll. The aggrieved teachers blocked the entrance of the Ministry of Finance, demanding their salaries.

“We are living, and you are referring to us as ghost names?” the protesting teachers shouted. “But we will die here today if you don’t pay us.”

Mr. Gongbehn Dekpah, chairman of the Deleted Teachers Association of Nimba County, headed the group of teachers from his county that also assembled before the Ministry of Education to protest.

“We do not have anybody to speak for us, because the ministry that is supposed to talk for us is saying our names are not on the payroll,” said Dekpah. “So whom can we go to?”

When Gueh was a DEO in 2004, teachers were paid in their own classrooms.

“Even though each teacher used to provide LD $200 to the DEO from their checks for transportation to bring their money, it was far better than using LD $3,000 to come to Cestos for pay,” said Gueh. “The teachers were happy with it, and it was advantageous to the students because their teachers were always with them.”

Gueh puts the blame for our country’s educational failings on the government’s lack of will power, not budgetary constraints.

“The government has the capacity to pay the DEO or civil servant,” said Gueh. “Because if you look at the revenue intake of this country in 2006, the budget was 80 million, but today we have about 540 million plus, so why can’t the government provide for its citizens?”

The Ministry of Education is working to find an answer, said Kpangbai.

“We don’t want our teachers leaving the classrooms for even a day, much more to talk about a week, so we are working along with the Ministry of Finance so that our teachers can be paid in the schools they are teaching,” said Kpangbai.

Another problem is the lack of support for the district education officers. DEOs are given oversight responsibility to act as eyes and hears for the Ministry of Education as well as transport instructional materials and school supplies to their respective districts. Yet often they cannot get enough gasoline to move around, especially during rainy season.

“We receive less fuel and lubricants from the government; sometimes we have to use our own resources in order to beef up government’s strength,” said Swary. “As DEO, I have 37 schools under my control and I receive [a slip for] five gallons of gas from the Ministry. But I have to burn eight gallons to go all the way Monrovia just to get the five gallons of gas.”

The shortage of gasoline supply for Rivercess has been repeatedly reported to the Ministry but nothing has been done, according to Monneh Duoe, county education officer (CEO) of Rivercess County.

“Not that I am happy about the situation, but if we say we won’t work because the gas is not enough, then we won’t work, because you don’t know if the gasoline will be increased,” said Duoe. “I make do with what I have, and I encourage my DEOs to do the same. I see this as a challenge that we have to face.”

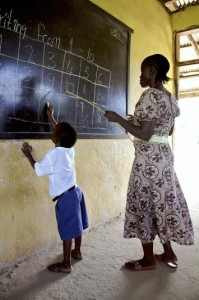

Yet another challenge is the lack of qualified teachers in Rivercess. Most active teachers don’t have the necessary education to teach their students, much less properly write reports for the DEOs and CEO.

“It poses a problem to the kids because these teachers are not trained in order to impact knowledge,” said Swary.

“Ninety-five percent of our teachers are high-school graduates or dropouts,” said Duoe. “Some of these teachers came into the system to help during the time when there were no teachers because teachers were not being paid properly.”

Liberia’s schools have 20,000 untrained teachers without a bachelor’s degree or associate degree from a teacher training institution – a number that former deputy minister Kpangbai acknowledged is “huge.”

“You can relate that to a multiplicity of problems – the issue of incentives, lack of opportunities, housing and transportation, as well as the challenges of getting their salaries,” said Kpangbai.

The government is trying to improve the educational system, Kpangbai said, but it will take time.

Critics argue that it will take a lot more than time.

“This country has the natural resources that can help you and me to live like 21st century citizens in the world. We should not be living in a Stone Age era,” said Gueh.

Senator Gueh called the government fiscally negligent toward education and toward Rivercess, one of the richest counties in Liberia in terms of natural resource production but one of the poorest in terms of government intervention.

The government has allotted only US $8,000 for teacher training for all of Rivercess County, according to Gueh.

“How many teachers can that amount train when Rivercess has 126 pub

lic schools and close to 500 teachers in the school system?” said Gueh.

Due to the distance and bad road conditions, many trained teachers are unwilling to go to rural regions such as Rivercess to teach. Meanwhile, the few trained teachers already in Rivercess are threatening to jump ship if their salaries and incentives are not increased.

“I will leave and go to Monrovia, where I can teach two schools and make more money to support my family, rather than stay in rural Liberia and my children be put out of school for school fees,” said George Cole, a BSc-level science instructor at Cestos High School who has 15 years of teaching under his belt.

A government incentive of US $500 to degree holders in rural areas would help draw trained teachers, said Cole.

Without such measures, even the acting principal of Cestos High School, Peter Cole, may join the exodus.

“I will also leave if nothing is done to improve our salaries and benefits because you cannot have a family that you won’t be able to cater to,” said Cole.

Many we spoke to on the ground say that if government cannot improve the educational system, the country won’t meet the millennium development goals.

”The government has been playing deaf ears to the various problems in Rivercess since it took power, and we cannot go far if things keep getting worse, said DEO Roosovelt Kofiako of Rivercess.

The ministry, on the other hand, is still promising to address the lapses in the system. Until that happens, students will continue to lag behind, waiting for their teachers to return to the classrooms to teach them.

Mae Azango is a fellow of New Narratives, a project supporting the businesses of leading independent media in Africa. See more at www.newnarratives.org. New Narratives and FrontPage Africa traveled to Rivercess in 2012.