In part two of a two-part series Rita Jlogbe Doue finds traditional leaders are defying a three-year moratorium and continuing to kidnap girls for bush schools.

GARPUE TOWN, Grand Bassa County – Few Zoes are as well known as 84-year-old Mamie Toe, also known as Zoe Mamie. The head of traditional women in River Cess she has been a leader on efforts to protect the Sande culture as government and international organizations have pushed hard to stop female genital cutting and bush schools.

Despite a three-year moratorium imposed by traditional leaders themselves at a meeting in Gbargna, Bong County in February, FPA/NN has found Bush schools have continued in River Cess, Margibi, Nimba and Grand Cape Mount counties. At least 100 girls are in Bush schools currently, many of them kidnapped and taken to the school against their parents’ will. Parents are being extorted to pay for their food.

By Rita Jlogbe Doue with New Narratives

Mamie Zoe says she is not surprised that it continues. She confirmed to FPA/New Narratives that the act is currently being practiced in Teekpeh, Gumu, and Gbowuzohn in Central River Cess District.

Mamie says though she is the head of the FGC practitioners in the county, she did not order anyone to kidnap children who should have been in school.

“Teekpeh Town and Gumu – they not check it but that right outside the women’s open Bush,” Mamie says. “Then to Gbowuzohn, they put some girls in the Bush – thirty-three girls. I don’t know about it.”

Mamie says she is not supportive of abolishing cutting which she says is a central part of Liberia’s cultural tradition. But she is supportive of it being done in a more medically safe environment and when formal schools are closed for a break. She says she is opposed to kidnappings and forced initiation.

But Mamie understands why Zoes persist. She has a message for government and organizations trying to end the practice.

“I told them that if we open the bush, they should help me to give caustic for those children to learn how cook soap. They should bring something them so the children can learn how to sew the country cloth,” Mamie says. “And they say they were going to do it. They don’t do it.”

According to the World Health Organization FGC is a harmful practice that involves the removal or injury of external female genital organs for non-medical reasons. It is a violation of women’s human rights and can have devastating health consequences, including haemorrhaging, infection, chronic pain, childbirth complications and, in severe cases, death. WHO estimates that more than 200 million of the world’s women and girls have undergone this procedure in more than 30 countries where it is practiced.

A bill before the legislature to ban the practice does not have the legislative support it needs to pass though backers hope it will in the next year. Liberia is one of just three countries in West Africa not to have made the practice illegal.

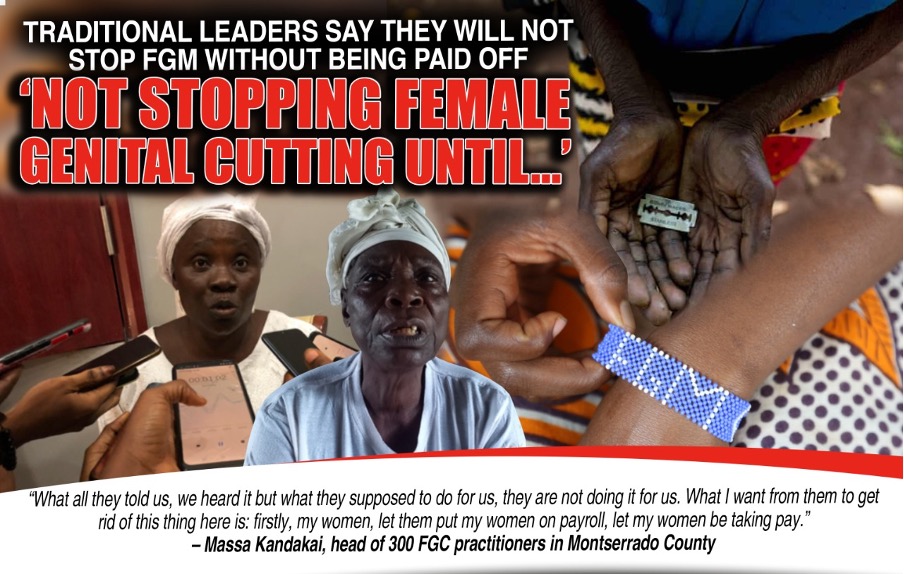

Massa Kandakai is the head of 300 FGC practitioners in Montserrado County: Photo by Rita Jlogbe Doue

UN Women has made a big push to address the issue this year. With finance from the European Union, United Nations and Government of Liberia, the “Spotlight Initiative” has been working to help traditional leaders replace income lost in Bush schools and find other ways to protect traditional culture. They have built or are building vocational and heritage centers in five counties designed to teach FGC practitioners new business skills and find other ways to protect and practice their culture.

One center is in Todee in rural Montserrado County where traditional leaders say they have suspended Bush schools after the construction of the center. But they warn they will only suspend the practice as long as hard cash comes their way. It is not clear they are interested in learning new skills to make money as UN Women intends.

Massa Kandakai, the head of over three hundred FGM practitioners in Montserrado County, says she along with her women have fulfilled their part of the bargain with UN Women by closing all bush schools in Sonkay Town and Todee in Montserrado. Kandakai says UN Women should uphold the agreement by continually supporting them – with monthly salaries, access to cell phone networks, fishponds and processors for making Farina or flour from cassava and potatoes. The women say they will revert to the practice if their requests are not met.

“What all they told us, we heard it but what they supposed to do for us, they are not doing it for us,” says Kandakai. “What I want from them to get rid of this thing here is: firstly, my women, let them put my women on payroll, let my women be taking pay.”

Kandakai is also calling for logistical support to enable her to travel to villages where she says the act is still being practiced, to ensure Bush schools there are shut down.

“My women can understand me, I Massa Kandakai, your support me let me go from bush to bush and put stop to them because they can understand me.”

UN Women Goodwill Ambassador for Africa on FGC and child marriage, Jaha Dukureh, a survivor of both from the Gambia, visited Liberia last month, holding talks with government officials, the diplomatic community, traditional leaders, civil society, women’s organizations among other stakeholders to advocate for the elimination of FGC.

As part of her advocacy, Dukureh recommends that there should be a dialogue with traditional leaders to practice “Initiation Without Mutilation”, an act she describes as teaching traditional norms without harming girls and women.

“Africa has beautiful cultures and traditions, and it would be nearly impossible for us to come into communities and tell people that they should abandon their traditional beliefs, there’s huge possibility that you will not be able to accomplish that,” says Dukureh. “But one way you can work with traditional practitioners is by allowing them to keep the positive aspects of those traditions that they want to keep without cutting girls.”

Liberia’s Vice President, Jewel Howard Taylor said the only answer to eliminating genital cutting is legislation.

“It has to be into law,” says Taylor. “The ban that has taken place by the traditional council is an attempt to say, ‘Yes, over the three years hopefully much more will be done to provide culture centers where our daughters can go and learn our culture and learn what it is to be an African woman without female genital mutilation’. So we hope the political will from the legislature will allow us pass this law.”

Political will seems a long way off. In September the bill backer Fonati Koffa, Deputy Speaker of the House, told FPA/NN that there was not enough support among legislators to pass the current bill. Traditional leaders have threatened legislators that they will lose their support in elections if they pass it.

For now heavy lobbying of traditional leaders continues behind the scenes. Many hope they will be persuaded to change their stance on the bill in the new year.

In part one of this two-part series Rita Jlogbe Doue finds “Bush” schools are continuing all over the country despite a three-year moratorium.

This story was a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the Investigating Liberia project. Funding was provided by the US Embassy in Monrovia. The funder had no say in the story’s content.