KPOLOKPALAH, Bong – It has been barely 25 years since the Kpolokpalah Massacre that saw the gruesome murder of more than 300 people by fighters from the Liberian Peace Council under the leadership of George Boley.

This story first appeared on Bush Chicken and Radio Gbarnga as part of a collaboration for the West Africa Justice Reporting Project.

Some of the deceased were residents and some internally displaced people who had fled fighting in Gbarnga. They thought they would be safe in this place, approximately a 35-minute drive from Gbarnga, just away from the Kokoyah Road that links Bong with Grand Bassa.

Survivors said the attackers were traveling from Grand Bassa to Gbarnga, Bong to battle with Alhaji Kromah’s United Liberation Movement-K and Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia forces for control of Gbarnga when they staged the massacre.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, in its final report, record 45 people killed. But two survivors – Isaac Redd and Nelson Dolo – said more than 300 people were killed in the massacre.

“After four to five years when we went for the communion burial, citizens of the town volunteered and brought the skulls and the body skeletons from the bushes, and so what I saw was between 150-400 human beings,” Redd said.

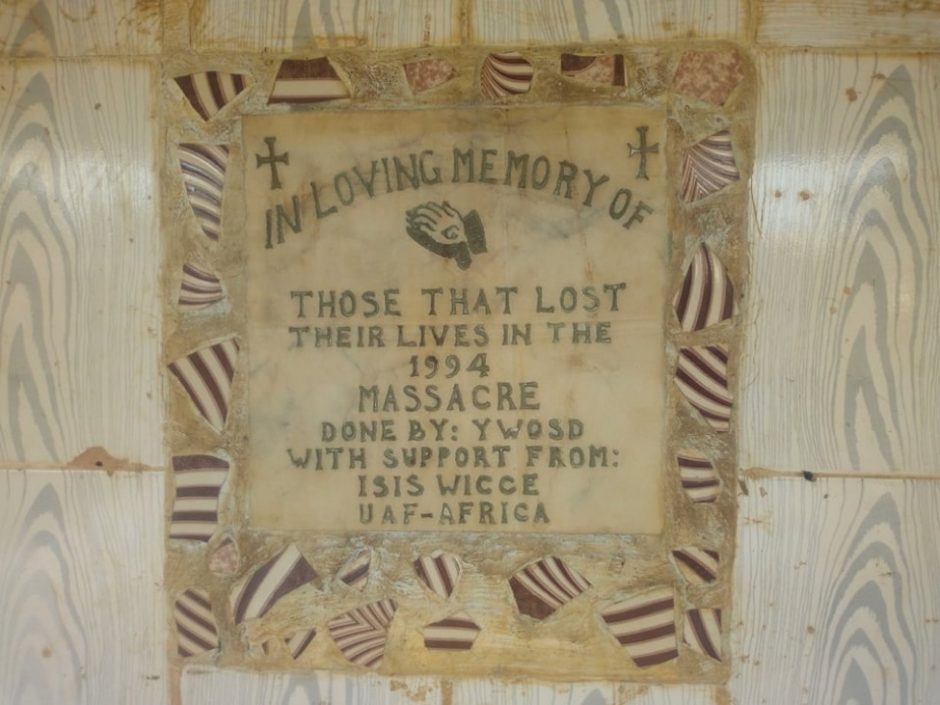

Dolo said he was part of a team of survivors and residents of the town that buried remains of the victims in a mass grave a few years ago. A headstone and plaque in a palava hut now mark the spot of the grave.

The survivors here said they want President George Weah to set up a war crimes court that will prosecute George Boley who was the leader of the LPC.

The TRC found that the LPC committed the third most crimes in the Liberian civil war (1989-2003). Only the NPFL (first) and the Liberia United for Reconciliation and Democracy committed more. The LPC ravaged towns and villages from places like Sinoe in the southeast to Grand Bassa in the west central.

Boley did not respond to requests for comment.

Dolo, who still lives in Kpolokpalah, said residents of the town and other people who fled fighting between the NPFL and ULIMO forces in Gbarnga were gathered in the town when the LPC fighters disguised themselves as NPFL soldiers and entered the town from Grand Bassa.

He said there were some NPFL fighters who had fled the attack in Gbarnga and were among the group of civilians in the town when the LPC fighters arrived.

“When they entered the town, they never introduced themselves as LPC soldiers. They behaved like government or NPFL soldiers and ordered everyone to assemble in the middle of the town,” Dolo said.

He said that the attackers told the few NPFL rebels in the crowd to disarm saying they had abandoned fighting in Gbarnga and were seeking refuge far away from the battlegrounds in Gbarnga.

The attackers then disarmed the NPFL rebels, tied them and placed them in the houses along with some of the people who were in the town, especially men, Dolo said.

“When they did that, they announced themselves as LPC fighters. And they started bringing people outside from the houses and killing them on the rock you see there,” Dolo said, pointing to a large, plateau-shaped rock in the middle of the town.

“The blood of the people they killed rolled from the rock all the way to the creek you passed before entering the town.” He said the attackers used machetes and cutlasses to kill their victims.

Nearly three decades on, Dolo is supporting the call for a war crimes court. “I [sic] happy for that to exist in Liberia because some of those people who did this thing, some of them still have that cruel mind. Tomorrow they can do the same!”

“This is why we are looking up to the government to discipline them or the international community can discipline them for that because we don’t have our own will,” Dolo said.

Even though Dolo said he no longer remembers the attackers, he is willing to testify in a court about what he witnessed during the massacre.

Boley was elected representative of Grand Gedeh’s second district in the 2017 elections in Liberia after being deported from the U.S. after many years living there with a permanent residency card.

In 2012, Boley became the first person in the U.S. to be charged under a then-new U.S. law criminalizing the use of child soldiers. The law said it didn’t matter what nationality the perpetrator was or where the act occurred. If the accused was on American soil, he or she could be prosecuted for the war crime.

Unlike the Philadelphia prosecutors who chose to try Tom Woewiyu and Mohammed Jabbateh for lying to U.S. immigration authorities about their war crimes (crimes that carried sentences as long as 110 years), prosecutors in the Boley case elected not to prosecute him.

War crimes cases are expensive and difficult to try. Very few prosecutors in the U.S. had undertaken such cases. So Boley’s prosecutors chose to deport him to Liberia instead, even though they knew there was almost no chance he would face prosecution under the government of then-president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

The decision to deport him angered many human rights activists who accused the U.S. of abandoning its responsibility to Liberian victims and instead of sending Boley back to live among them, some of whom had testified against him. Some victims have said Boley threatened them after his return.

Boley’s return to Liberia and election to the legislature was a blow to people like Gormah Kollie who lost her father, Kollie Nahnmelen, known then as ‘Coupert Light,’ the chief of the town. She lost other relatives, too.

She said the experience was horrible, as she saw LPC fighters carrying guns, sticks, and cutlasses that they used to kill her father and other people.

“When they took him from the house that night, he was crying. We were also crying with him, but the soldiers threatened to kill us along with him if we continued crying,” Kollie explained in Kpelleh.

She called for the prosecution of Boley and his forces for their actions.

“Let our president allow the court to come. We will not be free in our spirit if George Boley and those he sent here to kill our people be walking around free and we cannot see our people,” Kollie said.

Lorpu Kollie is another resident of Kpolokpalah who survived the attack.

She recalled that James Kpelewei, John Motor, and his wife Lorpu Motor, Mulbah Thomas, and Sam Lorpukollie, a classroom teacher, were among the citizens of the town killed in the massacre.

“Those who came here told us that it was George Boley who sent them here. We are only praying to God and appealing to the government to take action and allow the court to come to prosecute those people,” Kollie said in Kpelleh.

“It is the government that has the final say. We don’t have the power to make those people to be responsible for what they did to us here.”

NPFL and LPC are listed in the TRC final report among the ‘Significant Violators Group’ responsible for committing “egregious” domestic crimes, “gross” violations of human rights, and “serious” violations of the International Humanitarian Law, including economic crimes in Liberia.

Isaac Redd survived the massacre along with his mother and other siblings but lost his earlier brother, Francis Redd, Jr., who was a banker. Redd and family fled the fighting in Gbarnga and sought refuge in Kpolokpalah.

Redd said the LPC soldiers tied and placed him along with his late brother and other men in a room and later took them outside one by one, but it didn’t occur to him that those they took outside were being killed.

He said two leaders of the forces introduced themselves as ‘General T.’ and ‘Major Cash Shit.’

“They came and asked my bro: ‘Where is your gun?’ My brother said ‘No, I am not a solider, I was working at the bank.’ And one of the gentlemen said, ‘Oh you were working at the Charles Taylor’s Bank?’” Redd said.

He said following that conversation, his brother was taken outside and killed. Before then, Redd said one of the soldiers had shot dead one of the men the rebels had captured for attempting to escape.

Redd said he was saved from the massacre because he lied to the rebels that he was a friend to the children of an LPC general and that he had lived with the general’s family on 12th Street in Sinkor before the war. He declined to name the family for “security reasons.”

The day following the massacre, Redd said the attackers ordered that he and other men the rebels spared accompany them to Gbarnga with their belongings.

Interestingly, Redd is currently director of communications of the House of Representatives. That makes Boley one of his bosses.

Redd said he had told Boley of the ordeal he suffered at the hands of his soldiers. He told Boley he forgave him.

“I thought that was an embarrassing moment for him. His countenance changed, and in our conversation, I encouraged him to always see me as a son, and always see me as a staff – see me as a fellow Liberian – and that I hold no malice against him,” Redd said in a soft tone.

Redd said Boley’s greatest punishment should come from God, and not from a war crimes court.

“A war crimes court will not be a solution to healing the wounds that were created before, during, and after the war. I see the Kpolokpalah Massacre as an episode that should not be repeated by Liberians,” Redd said.

“I regret his loss, but what can I do about it?” he said about his brother murder. “Can I bring him back by thinking about what George Boley’s LPC did? Can I resurrect Francis Redd, Jr. by thinking about what ‘General T’ or [whatever] force did? I think the major punishment is coming from God,” Redd said.

For James Saybay, a rights activist and legal practitioner in Bong, the establishment of a war crimes court will bring relief to victims of the war and serve as a deterrent.

“I join the people of Kpolokpalah to call for the establishment of a war crime court to prosecute war perpetrators,” Saybay said.