It will come as no surprise to most Liberians that they are getting poorer. The average Liberian now lives on just $570 a year, down from $650 in 2013 according to the World Bank. That makes Liberia among the ten poorest nations in the world.

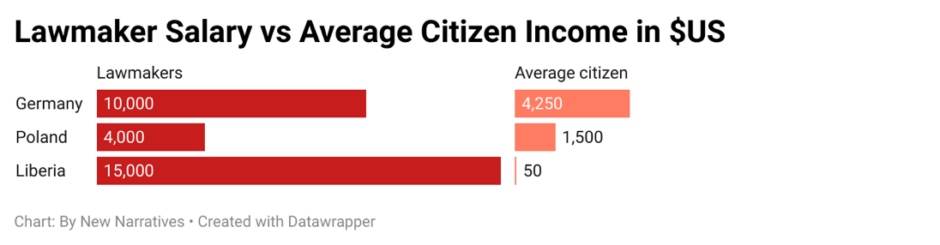

It may surprise Liberians then, that their lawmakers are among the world’s highest-paid. There is no official ranking of what lawmakers around the world earn but a few data points tell the story:

In Germany, with the world’s fourth biggest economy, lawmakers make a little over $10,000 per month, two-thirds of the $15,000 Liberian lawmakers are believed to take home. But while the average the average German lives on $US4250 a month, the average Liberian lives on less than $US50.

In the middle-income European country of Poland, legislators make about $US4000 a month while the average Polish citizen lives on $1500 a month.

High-ranking Liberian legislators such as the Speaker, Deputy Speaker, and Senate Pro Tempore can make more than their counterparts in the United States, the world’s biggest economy.

t has to change, says Dr. Nathaniel Barnes, former Central Bank Governor.

“It is quite obvious that they over-compensated compared to everybody else,” said Dr. Barnes in a zoom interview. “On average, a typical teacher in Liberia makes $150 a month. The legislators make about 100 times that amount, including benefits. Given the Liberian experience right now, who brings more value? I’m not trying to underestimate the value of the role that the legislators play, which is very important. A teacher is God’s gift to Liberia, we need to take care of them, and we need to make sure that there is equity across the spectrum. So the legislature should be the first ones to step forward and make the sacrifice.”

Dr. Barnes, who has announced his intention to run as an independent candidate for Liberian president in 2023, says he would do a systemic review of the system if elected to determine what pay rate is appropriate for a lawmaker.

Poverty in Liberia remains widespread, with nearly half of people living in extreme poverty – meaning they live on less than $1.90 per day. Roughly 2.3 million of Liberia’s five million people are unable to meet their basic needs.

The promised goal of President George Weah’s Pro-Poor Agenda for Prosperity and Development was to more equitably share the resources of the country and grow the economy for the benefit of all. But that is difficult with so much of the approximately $US800m annual national budget taken by legislators.

In the 2020/2021 national budget, the legislators appropriated $US44.6 million to themselves with Senators and Representatives taking home $US30,000 each for salary, expenses and the costs of running their offices according to the first ‘Legislative Digest’ released in July by NAYMOTE, the Liberian Accountability organization.

In the 2021/2022 budget, legislators allotted $US64 million to themselves including funds for items such as $US4.6 million for new vehicles and $US3 million fuel for those cars. By way of comparison, Liberia’s entire public education sector – for primary, secondary and tertiary levels – received $US92m in the 2022 budget.

Dr. Barnes is one of many national and international observers who say that given Liberia’s extremely limited government resources, they should be spread more fairly. Legislators he says, should remember they are public servants.

“[Legislators] use that authority as leverage to make sure that they are personally taken care of. And that is not right. There’s no reason why anyone in Liberia in public service should make $15,000 a month, including all of the benefits. We, as a people, we as a government, cannot afford that.”

As the global economy is buffeted by rising inflation and reduced food and fuel supplies caused by Covid, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and climate change, the inequality that Liberians see is starting to cause tension. Protests over price hikes have become common. Around the West African region, protests have spilled into violence and political instability.

That is concerning observers here. Interviews with regular Liberians suggest there is reason for worry.

Alex Gbe, 47, stands in a pool of water after his rough dwelling in the informal central Monrovia community of Fiamah was flooded because of sea level rise and poor drainage. The private security guard scratches to make a living for himself and two children. He says he is deeply frustrated that lawmakers have allotted huge resources to themselves without considering the plight of the poor.

“We elect these lawmakers and they do not only go home with fat paychecks, but they have glorious opportunities to embezzle national resources at different committee levels because of the lack of transparency in which they operate,” Gbe says.

A stone’s throw away from Gbe’s home Kollie Cooper, 62, is a former civil servant whose retirement salary is $US65 a month. He has lived in Fiamah since 2009. He says he is angry the lawmakers focus on personal interests above the interest of their constituents, and he sees little to zero oversight by the judiciary or executive on their financial activities.

“For now there’s nothing we can do than to hope for the best as we go to election next year, because that’s the only place we have power to correct whatever sufferings we have created for ourselves,” says Cooper. “And I pray that God open our eyes because we created the problem we are facing now, and it’s us that can solve it.”

Dr. Barnes says deeply rooted and institutionalized corruption underpins the problem. “The executive branch of government has used financial incentives – bribes – to get their agenda legislated and passed through the legislature. That is wrong. They try to bribe the legislature because much of the agenda is packed with corrupt practices. The executive branch of government should ask the legislature to pass bills on their own merits. They need to inform the people what they are doing and encourage the people to get in touch with their representatives and the senators to make sure that that piece of legislation passed because it benefits the people.”

Dr. Barnes says it will be hard to stop.

“We have painted ourselves into a corner. We have provided financial incentives to the legislative branch of government, and the legislative branch has emboldened itself and said, ‘Oh this is good, let’s take advantage of it’. So now we cannot move anything unless money and corruption is involved.”

The ‘Legislative Digest’ released by NAYMOTE found Liberian taxpayers spent $US164 million on the Legislature in the four years to June 2022. The report notes that it is impossible to get firm numbers on expenses given the absence of public records and the body’s refusal to submit to an audit. Even getting an official figure for lawmakers’ income was impossible. The Legislature office and the Speaker of the House did not respond to multiple requests for confirmation.

Cuts to public servant pay have happened before. In 2018, after years of demanding the government rein in inflated salaries, the World Bank, IMF and European Union forced the Weah administration to push through a “harmonization” process which saw salaries slashed for 10,000 public servants. The donors threatened to withhold $US61m in annual budgetary support unless government acted.

Legislators opposed the move. To get the cuts through the legislature the legislators’ salaries were kept out of the process. At the time Deputy Speak Fonati Koffa said he was not opposed to cuts in the legislators’ salaries even as he punted the issue down the road.

“I am for Legislative reduction, in fact, US$2,500 is sufficient for me,” Koffa said. “I am for legislative salary reduction but we don’t have to do it in the context of harmonization, we don’t need that.”

Darius Dillon was another legislator who condemned the salaries. In his 2019 campaign as senator for Montserrado County he promised to only take $US3000 a month and give the rest to his community.

NAYMOTE Executive Director Eddie D. Jarwolo noted after the harmonization process, the legislature budget actually grew from US$38.6 million to US$44.6 million. Jarwolo says the legislators have perpetuated the incorrect idea that they personally are responsible for doling out money for improvements and scholarships in their constituencies. But, he says, in a well-functioning government, the legislature makes decisions on how to dole out public funds, not legislators’ personal funds.

Jarwolo says the US$164m million spent on legislators over four years could have been used to more efficiently to provide basic social services to benefit the people including schools, hospitals and roads, that are desperately needed.

“It is not to turn the legislature into a welfare center,” Jarwolo says. “If you want to give scholarships, open national scholarship programs, and job opportunities so citizens can have a direct impact on their resources.”

International donors have kept up pressure on the legislature to cut salaries but Dr. Barnes does not hold out much hope they will move on their own. He says things will only change when every Liberian realizes that he or she has power and, that they can utilize that power by electing effective leaders.

“You have the power to create a better Liberia,” he says speaking directly to voters. “And the way you do that is selecting or electing those that will represent you best move away from voting for someone because they are popular with a wave of voting for someone because they are the same ethnicity as yourself. Elect leaders that understand your needs and represent your need, as opposed to those that are going there and line the pockets.”

This investigation was a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the Spotlight Liberia project. Funding was provided by the US Embassy in Liberia. The funder had no say in the story’s content.