MONROVIA—It is after 8 o’clock in the evening on the Barnersville estate, a low-income housing project on the outskirts of the capital of Liberia. The entire area is dark. A few candles illuminate small shops along the road. A path leads to Kollie Yard, a cluster of faded whitewashed houses surrounding a sand pit. The homes are modest; more than a hundred people share a common toilet. Saye Guinkpa has just returned home from central Monrovia, where he earns $250 a month working as a trainee at the Ministry of Justice. In a white T-shirt and khakis, the 30-year-old emerges from the two-room unit he shares with his girlfriend and two roommates. On the floor is a full-size mattress draped in a mosquito net. There is no electricity or running water. Guinkpa pays $15 a month for the privilege of living here.

With a degree in economics and accounting from the University of Liberia, Guinkpa earns more than four times what a policeman or entry-level civil servant can earn, and much more than the dollar a day that three out of four Liberians live on. Guinkpa says he was shocked to learn just how poor Liberia is compared to the rest of the world—a reality he only became aware of when he reached college. “It’s why I decided to press on with economics,” he says.

With a degree in economics and accounting from the University of Liberia, Guinkpa earns more than four times what a policeman or entry-level civil servant can earn, and much more than the dollar a day that three out of four Liberians live on. Guinkpa says he was shocked to learn just how poor Liberia is compared to the rest of the world—a reality he only became aware of when he reached college. “It’s why I decided to press on with economics,” he says.

In Liberia, income disparities are so wide that, in a sense, there are only two classes—very rich and very poor, with a gaping hole in the middle. A recent report by the African Development Bank Group estimated that only 4.8 percent of Liberia’s population can be considered middle class—the lowest percentage on the continent, among the countries for which such data is available. Only 15 percent of the workforce is formally employed, and 79 percent of those who are employed nevertheless do not enjoy a steady income, according to a recent Ministry of Labor survey. In this bifurcated socioeconomic landscape, people like Guinkpa are the closest thing there is to an emerging middle class—educated and employed, but hardly members of the elite.

While he enjoys his job and realizes he is fortunate, Guinkpa’s lifestyle does not match Western notions of middle-class comfort. He doesn’t have a television or a car. He wakes up at 5 o’clock in the morning to bathe outdoors with a bucket, in the privacy afforded by darkness. He spends half his income on shared taxis that take him to work downtown. A vacation is out of the question. His $3,000 annual salary may seem generous, considering that the annual average income per capita is $400. But in Monrovia, where an influx of foreign aid workers has resulted in double- digit inflation, the cost of living is high. Even the most humble roadside restaurant charges the equivalent of three dollars for a plate of food. “There’s no room for saving,” Guinkpa says. “It would mean I would have to starve.”

Guinkpa aspires to become a financial analyst for the government, earning twice what he now takes home. He fears that, instead, he will have to work a lower-paying job his entire life. He believes that the fact that he was educated in Liberia—and not abroad, like some children of the elite—ill keep him from any kind of real upward mobility. “Someone who graduated abroad has vast experience, he has learning with technology that’s far ahead of you,” he says. “When he comes back and you and he go for a job in a competitive market, he will win.”

THE COSTS OF CIVIL WAR

Following 14 years of civil war that ended in 2003, the country has had to rebuild state institutions from the ground up, repair a shattered national infrastructure, and above all help individual citizens contribute to economic growth and the rebuilding of the state. The war was a stark example of how class inequality can stir unrest. The country’s traditional elites are the “Americo-Liberians,” descendants of the freed American slaves who founded the country in 1822 and, ever since, have oppressed the descendents of the indigenous people their ancestors encountered upon arrival. In 1980, the indigenous-descent population rose up and overthrew the Americo-Liberians. Reeling from widespread corruption and economic mismanagement, the country remained highly unstable, as factions within the new power structure fought for control. Liberia finally erupted into full-scale war in 1989, when Charles Taylor, a former Liberian government minister who had fled the country and was living in Cote d’Ivoire, invaded with the backing of Libyan President Muammar Gaddafi.

The elite, including most skilled and educated workers, fled the country, and the economy collapsed. According to government figures, GDP fell 90 percent between 1987 and 1995, one of the sharpest economic collapses ever recorded in any nation. By the time of the first postwar elections in 2005, average income in Liberia was just one-quarter of what it had been in 1987, and just one-sixth of its level in 1979. By 1993, agricultural production—historically the most significant contributor to GDP—had dropped by 75 percent from its 1979 level, as people fled their farms.

Still, peace has paid some dividends. By 2008, agriculture had returned to 61 percent of GDP, according to the World Bank. And the economy is unquestionably expanding, with annual GDP growth averaging 9 percent since 2004.

MIDDLE CLASS, OR WORKING POOR?

Chid Liberty owns a garment factory in Monrovia that employs 40 people, mostly women. He plans to scale up production over the next 18 months and eventually employ 900 people. Most of his workers earn $100 a month, plus a $30 transportation stipend and a bag of rice. The company also provides healthcare and a 100 percent annual savings matching program. Liberty’s father was Liberia’s ambassador to Germany during the regime of Samuel Doe, the Liberian soldier who overthrew Americo-Liberian rule in 1980. Liberty’s family later fled the country and went into exile in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Liberty is now one of the growing number of Liberian exiles returning to help rebuild the country.

“If anyone says, ‘Yes, there is a middle class in Liberia,’ I believe they have the middle class confused with the working poor,” he says, sitting at the restaurant of one of Monrovia’s few high-end hotels. “I don’t think a security guard earning $60 a month can be called middle class, when one bag of rice could cost him $40. There’s no way to support a family there.” While Liberty would like to pay his own employees more, he sees Liberia’s low wages as a competitive advantage that he must exploit.

Liberty believes cultivating a middle class will require investments in small and mid-size businesses like his, which might allow him to become profitable enough to raise salaries. “As we move forward with larger corporations coming in now—which I’m in favor of, because they do provide some level of employment—they’re not going to have jobs for a lot of Liberia’s working poor,” he says. “And I really think it takes a concerted effort on behalf of Liberian entrepreneurs and our policymakers to figure out what types of industries we can bring in that specifically target jobs for the poor. I’m not sure that oil companies or many of the major concessionaires are going to do that.”

BRIDGING THE GAP

To bridge the gap between the poor and the rich—to help build a genuine middle class of families that have managed to bootstrap themselves out of poverty—Africa’s first female president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, introduced the Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS) in 2008. The three-year, multi-pillared plan stresses the creation of a middle class through the attraction of foreign investment, which Johnson Sirleaf believes is critical to the growth of the economy. It also aims to empower domestic entrepreneurs to conduct business and create jobs by expanding microcredit and investing in infrastructure, increasing the size and purchasing power of the Liberian middle class. More than 200,000 new jobs have been created since Johnson Sirleaf took office in 2006, according to the government. At the same time, the Central Bank has injected $5 million into the domestic economy under a credit stimulus initiative for small and mid-size commercial borrowers, which also involved reducing interest rates from 14 percent to 8 percent.

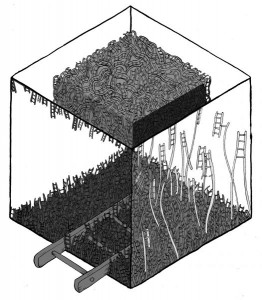

Critics point out that income distribution has remained virtually unchanged since the PRS was introduced in 2008 and that, according to World Bank figures, 3 out of 4 Liberians are still living below the poverty line. Yet Amara Konneh, the Minister of Planning and Economic Affairs, proudly lists a number of major rehabilitation projects—the building of roads, schools and hospitals—as evidence of the success of the PRS and the government’s plans for the development of a middle class in Africa’s oldest republic. “I think we’ve begun the process,” he says. “The economy is picking up and I believe that within the next five to 10 years we will see more people in Liberia climbing the ladder from poverty into the middle class.”

With the PRS set to expire in August, the government is introducing a new plan, Liberia Rising 2030, that aims to make Liberia a middle-income country—defined by the World Bank as a country with annual per capita income of around $4,000—within 18 years. The government has already met some important milestones. Last year GDP grew by 6.3 percent, up from 4.6 percent in 2009. This year the IMF projects the economy will grow 5.9 percent. Since 2006, income per capita has risen by a third.

In Konneh’s vision, Liberia Rising 2030 is a long-term project that will create a genuine middle class—people who will own their own homes and drive their own cars, provide their children with a decent education and quality healthcare, and possess enough disposable income to go on vacation. “There’s never been a Li- berian Dream,” Konneh says. “When you ask people about the good old days, they tell you about people driving Jaguars. Now, those are the people in the upper class. Then you have the lower class. There’s no middle,” he added. “So what we’re trying to say is, let’s create a Liberian Dream.”

So far, the government’s strategy to increase GDP has focused on foreign direct investment, an approach that some say has placed too little emphasis on developing the domestic economy. Foreign direct investment rose from $2.8 million in 2002 to $378 million in 2009, according to the World Bank. Despite the government’s efforts, however, the private investment landscape in Liberia remains relatively limited, with the exceptions of Arcelor Mittal, which mines iron ore, and a 2.5 million acre concession—the world’s largest rubber plantation—given to Firestone.

Nevertheless, Liberia is rich in natural resources, including timber, iron ore, gold and diamonds. Most of the population lives off the land, but there are also a number of large commercial farms. As more foreign investments come online, GDP is expected to rise. California-based Chevron, which acquired three deepwater blocks last September, will start looking for oil and gas off Liberia’s coasts by the end of the year, and employ Liberians in the process. Libe- ria also recently signed agreements with Indonesian palm oil company Golden Veroleum, Anadarko Petroleum and iron-ore miner China-Union Ltd.—all pledging to support the country’s social and economic development, but also eager to exploit its abundant natural resources.

These investments are an “expression of confidence in the leadership and future of Liberia, which are essential conditions to attract other major investors in all sectors of the economy,” President Johnson Sirleaf told The Wall Street Journal. “The creation of jobs and the revenue of possible oil finds will transform the econ- omy through infrastructure development.”

UNCHANGING BARRIERS

Despite five years of free-market policies that have drawn billions in public and private investments, life remains a struggle for Saye Guinkpa and thousands of others like him, with degrees and jobs but not much hope of advancement. Even as the private sector grows, a government job is still the only guaranteed path to upward mobility. After all, senior government staffers certainly don’t ride in shared taxis, and some can even afford to live in luxurious compounds with round-the-clock security and ocean views. But many talented young people like Guinkpa face seemingly immutable class barriers based on descent and skin color. Even after decades of violence and upheaval, lighter-skinned Americo-Liberians remain seated at the highest echelons of public life—a reality unchanged, so far, by the country’s nascent economic development.

The most that seems possible, for the moment, is a move out of what is effectively an urban underclass—one broad notch above subsistence—into what has the prospects of becoming a middle class, at least in Monrovia itself. For his part, Guinkpa remains undeterred by the fact that he has no immediate prospects for anything beyond that. “It motivates me to work harder,” he says.