By Anthony Stephens and Prue Clarke. Photography by Carielle Doe

Life was bleak for 22-year-old Esther at the end of 2021. Living in her pastor father’s church compound in Monrovia, she had no job, no education and few prospects. The pandemic and global economic turmoil had hit her father’s parishioners hard. He could no longer send his six children to school. Esther spent her days doing odd jobs and dreaming of a different life.

When Esther’s friend Princess came to her with a job offer overseas she thought her dreams had come true.

“She told me she was traveling to Dubai and her uncle had a job opportunity there,” says Esther sitting at a table in the church with her mother and father. Esther’s father Michael was suspicious. He demanded to speak with Princess’s uncle, a man named Samuel Chan Chan. Chan Chan promised Michael the job was legitimate. Esther would work in a printing press in Dubai making $500 a month. That was a princely sum to a Liberian family where GDP per capita is $630 a year and schoolteachers make $150 a month. Michael agreed.

“I was happy to help my family, my brothers, my sisters,” Esther says. Esther and Michael are not their real names. We are hiding their identity to protect them from reprisals.

Chan Chan told the family they needed to pay $500 to his wife Eve, based in Monrovia, and get a passport and a Covid test. The family scraped the money together. Then one night in December Esther and her parents got into a taxi, drove to the airport and said a teary goodbye. As she disappeared into the terminal Esther carried the weight of her family’s dreams of a better future.

Inside the airport Samuel’s brother Arthur, a national security agent, whisked Esther passed security checkpoints where agents are trained to spot potential trafficking victims. Arthur demanded $75 for his services.

Alarm bells started for Esther before she got on the plane. The visa Arthur gave her was for Oman, not Dubai. When she landed, an Omani woman demanded she hand over her passport. Wary, Esther refused at first, but she eventually gave in. Over the next few hours the reality of her situation became clear.

Esther was taken to an office filled with women from different parts of the world – Bangladesh, the Philippines and many African countries. It was an agency supplying domestic servants to Omani households. In a scene alarmingly reminiscent of African slave trades of old, Omanis came in to inspect the women and haggle over price. Asians – considered harder workers – cost more. Africans the least.

It was here that Esther says she “first learned about this thing called ‘human trafficking’”.

Typical modern slavery scams in the Middle East are orchestrated by agents who sell domestic servant contracts to households. In Oman the households pay a $1500 fee to the agent as well as the costs of return flights. Households typically pay the servants $200 a month for long days with no days off. The contract lasts for two years.

The challenge for agents is that even the poorest women are not interested in that deal. So the agents enlist local people like Samuel Chan Chan to deceive the women with promises of decent jobs, opportunities to study and no mention of the contract. When the women want out they’re told the only way to get their passports back is to repay the fee.

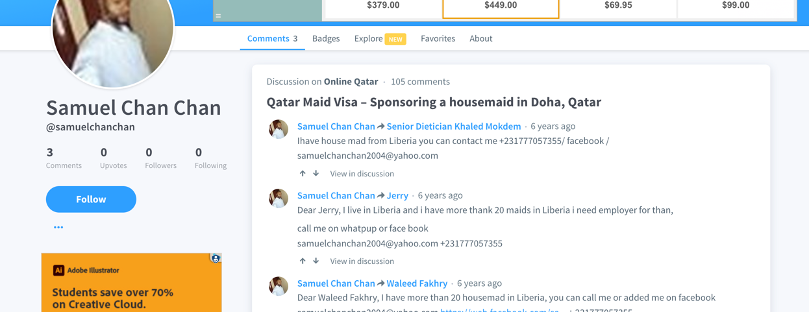

Chan Chan did not need much encouragement to sell out his fellow Liberians. His online history shows that after winning a fellowship to the Arab Africa Summit in Egypt in 2018 he started offering his services on forums recruiting workers in the middle east.

“I have more than 20 maids in Liberia i need employer for than (sic),” he says in one post.

By 2021 he had relocated to Dubai and made connections with Omani agents including Al Ayadi Al Amina Housemaid Supply whose business card was obtained by one of the trafficked women. Liberian authorities say more than 350 Liberian women were lured to Oman by the ring in 2021 and early 2022. Chan Chan did not respond to requests for comment sent to through Facebook messenger.

Esther found herself working in a house with fifteen people in ten bedroooms and eight bathrooms. Only the mother spoke enough English to communicate with her. Esther says she had to wake at 4am, prepare breakfast, get the children ready for school and then clean all day and cook. The family ate first and she got what was left over.

“And when they eat the food and there is not enough, they will not give you food to eat,” she says. She often went to bed at midnight. She was not allowed outside the compound and got no days off.

After a couple of weeks Esther refused to work. The agent moved her to another house and another. At one point he beat her and broke a finger. She shows her crooked left ring finger that is healing on an angle. Eventually the agent had Esther arrested on a fake charge that she had stolen his phone. She says she was imprisoned in a dark cell, with no light for ten weeks. Five other African women in the jail were beaten and starved. She claims one, from Tanzania, died.

“It was like hell in the prison,” she says struggling to contain emotion. “Too much hell.”

Esther’s story echoes that of five other returned trafficking victims we spoke with in this investigation. One says she was raped. All were beaten.

Esther told her agent she wanted to speak with Chan Chan. That’s when she learned the truth. “He said he bought me for $US3000 from Samuel Chan Chan,” she recalls. “He said you can go home but first you have to pay me the $US3,000.

In Monrovia Esther’s parents were desperate. Sporadic phone calls from their daughter terrified them. The traffickers were also calling, threatening to kill Esther if they didn’t pay her fee. Michael called everyone who might help. Police, government officials, other families, and Chan Chan. Over and over again.

He shakes his head at the memory. “To have a child go there to try to help the family. For her to see it and say, ‘because of our poor condition I’m going to go and find something to help’ and then to end up in jail. It was very painful.”

For most of the millions of victims of trafficking this is where it ends. Desperate poverty brought them there in the first place. Some families will stretch themselves to breaking point to borrow the money to free victims from the contract. But most are trapped, at the mercy of agents. Even when the contract ends many agents pressure victims into another.

But the Liberian women in Oman were not willing to give up. Some had sneaked in Liberian sim cards – hidden from the agents – and started contacting family and each other. They formed a WhatsApp group. A friend suggested they make a video.

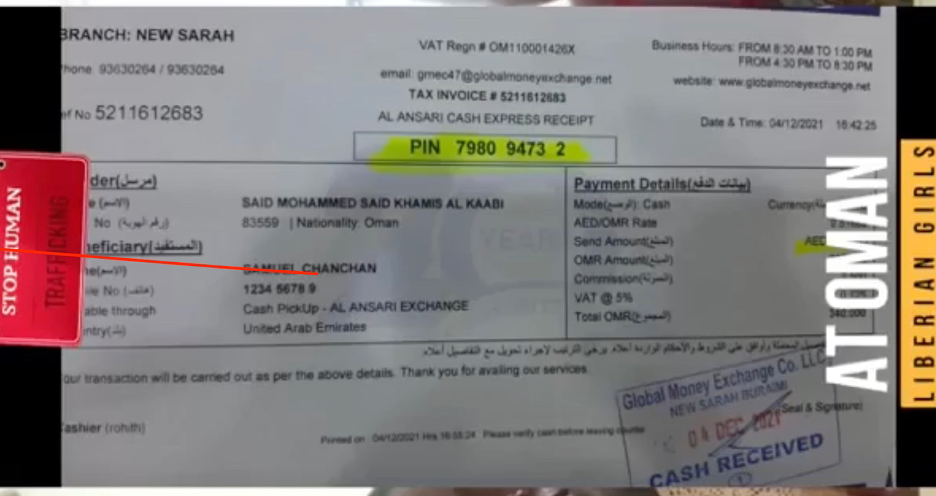

“We were sent here by some guys who call themselves ‘agency’,” says a woman on the video surrounded by Esther and five other women. “They lied to us. We never knew it was all about this human trafficking issue.” Her speech is intercut with videos of a woman fighting two Arab men trying to hold her. Other shots show women crying as they sweep floors. The video also shows a payment slip that Esther found showing Chan Chan had received money from the agent, an Omani named Said Mohammed Said Khamis Al Kaabi.

Oman has laws against the mistreatment of domestic workers but they’re rarely enforced according to people who have helped victims escape. An African woman claiming she was deceived into a contract is never believed. Authorities only act when the woman can prove physical violence, which is rare. Omani authorities did not respond to a request for comment.

The video and the women’s desperate calls from Oman made it to Liberian newspapers, Facebook and radio talks shows. Parents demanded the government act. The Liberian government also faced pressure from a different source. After years on and off the United States Congress’s Trafficking in Persons WatchList the administration of President George Weah faced a cut in badly needed U.S. aid if it didn’t step up efforts to combat trafficking. The U.S. provides more than half Liberia’s $200m annual foreign aid, equal to 12% of the annual budget.

Diplomatic communiques were sent to the Omani government. Oman agreed to stop granting visas to Liberians. The women found two key allies: an African working undercover in Oman to help trafficking victims and Canadian Ward Reddick who had taken it upon himself to help African trafficking victims after a Ugandan friend had been caught in a scam and he had been unable to find anyone else to help. The pair worked with a Liberian consular officer in Dubai who was given full authority to help the women.

The group set up safehouses. But the women still had to escape the agents. The first women to escape jumped over the walls of the compounds where they were working. Two told the Continent that they spent three terrifying weeks hiding in the streets of Muscat, eating out of trash cans before other victims connected them with Reddick. As time went on the consular official, communicating secretly with Esther and the other the women through Whatsapp, sent cars to collect them. He issued travel documents. Omani authorities let them go.

Six months after the first women left they started to arrive home. Officials with Liberia’s Anti-Trafficking Unit say more than 250 of the estimated 350 have returned. The outcome is unprecedented according to Drew Engel, anti-trafficking adviser at the US Embassy in Monrovia.

“I’ve never heard of anything this size, a group sort of mobilizing, organizing, however, they managed to do it. I’ve never heard of anything quite like this in my probably 15 to 20 years of being involved in countering trafficking in persons cases.”

For Reddick, the women’s solidarity through the long fight is a lesson for others. “One of the worst parts of being a victim of modern slavery is the isolation,” he says in a call from his home in Vancouver. “It’s the belief that you’re truly, absolutely alone, and that nobody cares. Even your family may not be willing to put up the money to bring you home. That’s when they can really go downhill. The women bolstered each other’s hope, in a really positive way. They never felt alone. They never felt isolated. And in some small way, that is a bit of control over your life.”

Eight months after she left home trying to change her family’s fortunes, Esther landed in Monrovia. Sitting in the family’s compound tears spring to Esther’s mother’s eyes at the memory of seeing her daughter emerge, finally, from the airport.

“Tears of joy,” says her father Michael smiling. “I was so happy. I was acting like a man. I did not shed tears but I was deeply, deeply thankful to God. It was a very, very joyful day for us.”

A Liberian court has asked police to issue an international arrest warrant for Samuel Chan Chan who is believed to be in the Middle East. His brother Arthur is serving a 25-year prison sentence after his conviction for trafficking earlier this year. It’s the longest sentence ever given for trafficking in Liberia. In 2021 the Liberian legislature had made the minimum sentence for trafficking 20 years.

Esther was one of two women who testified against Arthur. He was ordered to pay her $6000 in restitution. The money would change her life but she has little hope of seeing it. Though Arthur is estimated to have made more than $26,000 for his part in the scam, authorities have done nothing to seize his assets while he appeals his conviction. Esther is looking forward to seeing Samuel in the dock. “He (Arthur) is not the one I wanted to see in jail.”

Engel says the outcome is an important example for governments across Africa of what can happen when a government is motivated to stop trafficking. But in the end, he says, credit goes to the women.

“The victims, complaints and WhatsApp groups in the media became very powerful tools to raise awareness about the situation and make it rather untenable for employers and agencies and others to keep many of these women in Oman against their will,” Engel says.

For Esther and the other returnees life is no easier than it was when they left. But they are grateful to be home. They are now united in fighting for psychosocial support, job training and justice. Esther has been threatened for testifying. Though the government has not provided her with protection she’s not stopping. She wants other women to know that if something sounds too good to be true it probably is.

This story was a collaboration with The Continent. Expenses were covered by the International Women in Media Foundation.