TAPPITA DISTRICT, Nimba County – This disarmingly peaceful forest area in Liberia’s far north Tappita District has been the scene of conflict of one form or another for decades. But since 2014 it had enjoyed some peace as two clans here, supported by a US-backed project known by the acronym PROSPER, agreed on a boundary line between them.

But that peace has been upended again as the Krahn dominated Gayea Clan, and the Gblor Clan, predominantly of the Gio, square off over one clan’s claim for customary title as allowed in the 2018 Land Rights Act.

“We were very excited when PROSPER came to demarcate our land. We, along with our women, spent days sleeping in tents in the forest for a successful completion of the process,” says J. Beauregard Bah, spokesperson of the elders of Gayea clan and Principal of the Zodru Public School. “But the people of Gblor Clan, because they are in majority, want to deny us of our land.”

This dispute is one of an unknown number of conflicts roiling rural areas in the wake of the Act’s passage. The Weah administration rushed the Act into law in a bid to give communities that had lived on customary land for generations, legal ownership of their land. But authorities tasked with overseeing the process have been overwhelmed.

Tensions have flared up again here as the Gayea clan has sought to claim their rights under the Land Rights Act to part of the 11,957-hectare forestland that lies on the fringes of the Gio National Forest and stretches along the banks of the Cestos River at the Liberia-Ivory Coast border.

The clan says it wants to make a deal with logging companies to extract timber from the forest. They say they want to use the funds to improve the only clinic serving the entire population, upgrade the school, provide hand pumps and build roads linking the clan with other settlements.

The Gayea clan also says it wants to conserve a portion of its forest. The clan had worked with Parley Liberia, a civil society organization that is guiding a number of communities in Nimba, Lofa, and Bong Counties to legally own their lands. It had completed all the first two of the five steps required by the Act to claim customary land title: it self-identified itself and completed participatory mapping of its land. But when it came to step 3, harmonizing its boundaries with its neighbors, the problems began.

Gblor protested that it would not accept the demarcation decided through the PROSPER project. Elder John Miah of Gboutuo, a boundary town in Gblor Clan, says his people were fooled by Gayean leaders during the 2014 negotiation.

“When they went on the side leading to Cestos River, we allowed them to claim their farm and villages that were on our side of the boundary, but when we headed towards the National Forest, they refused to do the same to us. Our farms, rubber and villages were taken away.”

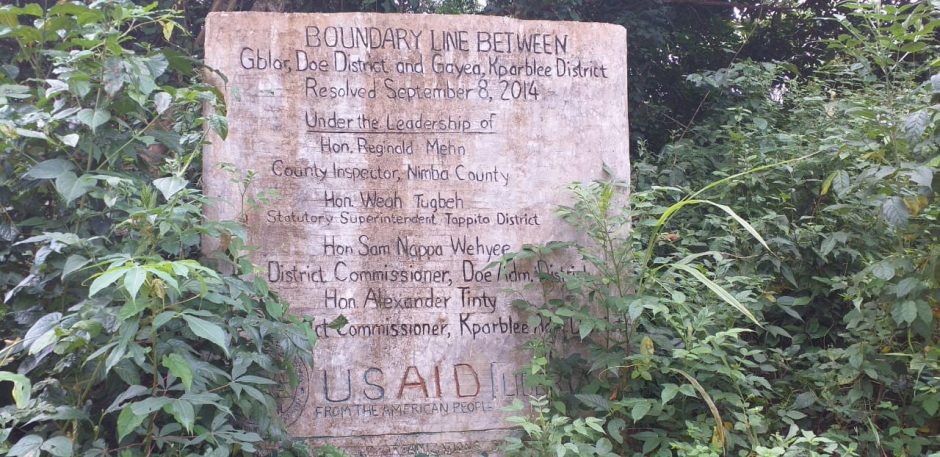

But Gayea Clan elder Bah claims that during the demarcation, both parties agreed with the boundary that was drawn up. He points as evidence to the monument erected at the starting point of the boundary and the resolution signed.

Bah says the Gayea clan inherited the land from their ancestors who arrived from what is present day Ivory Coast in the 17th century.

“Our ancestors were the first to arrive here and take up settlement,” Bah says. “It was because of their presence that the Gio and the Mano moved further inland when they came later. That’s why this town [Zodru] is the oldest in Tappita District, and was the first headquarters of the Chiefdom.

But Gblor disagrees with the narrative. It claims that during the demarcation, most of its land leading to the Cestos River side of the boundary was given to Gayea because of an appeal by Gayea and the PROSPER project managers to stop Gayea from losing its farms containing rice and other cash crops. But on the side of the Gio National Forest, Gayea refused to reciprocate Gblor’s gesture and all of its land containing villages and farms with cash crops was taken away.

The demarcation, says Elder Miah, was politically motivated. He claims the disputed land belongs to Gblor’s forefathers but the trouble began in the 1900s when they decided to give a piece of the land to a son of Gayea named Bah who was married to a daughter of Gblor. According to Elder Miah, Bah began to go beyond the land given him and after he died many years later, his children and the people of Gayea Clan decided to claim ownership of the entire forested land.

“The good thing our people did is now affecting us.”

The coordinator of the PROSPER project, Nuahn Biah, did not respond to calls and a series of text messages seeking comment.

However, Tetra Tech ARD, a United States-based company tasked with implementing the 5-year US Agency for International Development funded PROSPER project, said in its 2014 report that it had completed the demarcation between the two clans.

Following the demarcation, according to the report, the citizens developed a resolution agreeing to the boundary and erected a monument at the starting point of the demarcation to commemorate their success in resolving the long-standing dispute.

Fear for the Future

The Gayea forest, along with nearby Gio National Forest, is a protected area and home to some of Liberia’s 2,000 rare plant species. Some of the country’s 125 mammal species, 590 bird species, 74 known reptiles and amphibians and over 1,000 described insect species are found in the forest. The forest is also a habitat for endangered species, including the West African chimpanzee, pygmy hippopotamus and Jentink’s duiker.

This rich biological diversity is threatened by farming and hunting. The area is a major hub for the illegal bushmeat trade as hunters flood the forest, waging war on these endangered wildlife species.

“I want to shed tears because our forest is being depleted. It may turn into a savannah land,” Bah says. “There would be nothing left for our children. The upcoming generation will get nothing.”

Annie Poquee, head of the Gayea’s land committee, speaking through an interpreter in her native Krahn dialect, explains that the crisis is hurting women’s livelihoods. Poquee laments that the creeks and streams used for fishing and fetching water are being polluted by their neighbors, who use a fishing method that is anti-conservation.

“Since PROSPER left from here, the boundary lines we all agreed to, have been erased by Gblor people. They made a farm and their women are fishing in our creeks. They block the water from upstream and downstream, then in the middle, they pull out all the water and kill every living thing including the big fish and baby fish.”

Gblor rejected their neighbor’s claims.

“We all depend on this forest to survive. The hunters in the forest are from both sides of the clans, not just one side, we have our portion and they have theirs,” Michael Zor, youth of Gbotuo responds.

Parley’s Pledge to Return

Parley Liberia says it pulled out of the harmonization process because of mounting tensions between the clans. The CSO does not settle disputes. It only works with clans after they have settled on boundaries. However, Nyan Flomo, Parley’s Program Coordinator, says the interference of relatives living outside of the areas is one factor blocking resolution.

“When residents on the ground seem to be reasoning, the next day somebody will call from outside and say no, don’t do that, don’t agree,” Flomo says.

LLA Fails to Act

Article 35 of the Land Right Act calls for the establishment of a Community Land Development and Management Committee (CLDMC) to, among other things manage the customary land and settle disputes. In this case, Flomo says only Gayea has set up a CLMDC, but could not independently settle the current impasse between the two clans because it will be seen as biased. Only the Liberia Land Authority (LLA) can intervene, he says.

FrontPage Africa reached out to the LLA on several occasions to speak about its intervention in the dispute, but the agency declined.

At one occasion, as this journalist awaited an interview at the LLA officer, he over heard the LLA agent responsible for customary land formalization saying that the LLA was “not answerable to the press”. He refused to sit an interview that was being arranged by the LLA public relations officer.

One former government official in the area says the matter should be quickly settled. Former Commissioner Sam Nappa Wehyee of Doe Administrative District which covers Gblor Clan, was part of the boundary demarcation exercise in 2014. He says the demarcation is legitimate. He calls on officials of both sides to engage their citizens to accept the boundary for the sake of peace.

“I don’t think the people of Gblor Clan will go against the boundary. I believe it is just a misunderstanding,” he tells FrontPage Africa. “The monument between the two clans is clear evidence, and I believe when the leadership of both areas muster the courage to tell their people that the boundary is genuine and all should accept it and live in peace, they will agree.”

This story was collaboration with Front Page africa as part of our Land Rights and Climate Change Reporting Project. Funding is provided by the American World Jewish Service. The funder had no say in the story’s content.