“I like to talk to the common people, I don’t like politics.”

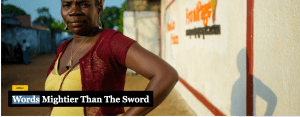

Mae Azango sits on the edge of her bed in her old home that is wedged in a rocky enclave between the gray United States embassy and the modern apartments occupied by expatriate workers in Mamba Point, the poshest part of Monrovia, Liberia. Azango’s larger-than-life personality fills every inch of the dim, cramped, lemon-colored room where she lives with her 11-year-old daughter, Madasi. Within five minutes Azango has hijacked the interview and is yelling out the story of how she came to be one of the best-known female journalists in Liberia. Without a hint of irony, Azango refers to herself in the third person, claims to be a household name and universally feared by Liberia’s political establishment; then announces to President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf that she will never compromise herself by taking a job from her.

Some might say Azango likes to bluff or show off, but the 41-year-old single mother is one of a new generation of headstrong female journalists, who are not afraid to compete with their male counterparts or reel off lists of their achievements.

“This breed is more aggressive than what we had before,” says Elizabeth Hoff, who was the first female managing editor of a Liberian newspaper and the first woman to be elected president of the Press Union of Liberia (PUL).

Hoff, who now serves as deputy information minister, remained an editor throughout the heat of Liberia’s 14-year civil war that ended in 2003. She says a lot has changed since she worked in journalism, when many women left the profession out of fear for their safety. Those who stayed on fought sexism and struggled to win respect from their male colleagues.

Azango is one of a handful of female journalists in Liberia who have not only earned respect from their male colleagues, but also international recognition. She is part of New Narratives, an organization that supports independent media in Liberia. Founded and headed by Prue Clarke, an Australian foreign correspondent who reported in Africa for a number of years, the organization was set up in 2010, with funding from a Goldman Sachs partner. New Narratives teamed up the muckraking daily newspaper FrontPage Africa, for which Azango and the other fellows work.

These reporters have driven much of the hard-hitting reporting on violence against women and girls in Liberia, ranging from stories on child rape, teen prostitution, maternal health, corruption and education, for which they have won domestic and international accolades.

Azango received the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) International Press Freedom award in 2012 for her controversial reporting on female circumcision, a practice that takes place in the traditional Sande societies that exist within 10 of Liberia’s 16 tribes. She says she received death threats and was forced into hiding, moving from house to house and avoiding the newspaper office for a month. Mohamed Keita, the advocacy coordinator for CPJ’s Africa Program, described Azango as “outspoken”, “fearless”, and “persistent.”

But this was not the first time Azango had experienced threats of violence. Like her other female colleagues who are part of New Narratives, Azango’s experiences of coming of age during the war compelled her to become a journalist and report on the struggles of women and girls.

Azango recounts, in vivid detail, a memory from the early days of the war, when she was 18-years-old and pregnant with her first child, Victor, who is now 22. She says the pregnancy saved her from being forcibly taken as a girlfriend by a rebel.

Charles Taylor’s forces had closed in on Monrovia and Azango was picking potatoes around her home. She kept crossing a checkpoint that was controlled by a fierce commander.

“‘Why am I keep seeing a pregnant woman?’ he yelled. ‘I am looking for a young girl and she is spoiled, why is she in front of me? At the count of five if you don’t disappear I will spray you.’ I was running like a cut, dead dog,” says Azango.

With a father who was an associate Supreme Court justice and a mother who was a teacher, Azango initially aspired to be a hotel manager. But after 10 years of war in her homeland, Azango’s memories of a privileged childhood were replaced with raw experiences of being a poor refugee in neighboring Côte d’Ivoire.

When she returned from exile in 2000, Azango studied journalism at the University of Liberia and has never looked back. Unlike most journalists who focus on the sensational stories surrounding the political establishment, Azango writes about the masses, the ordinary Liberians who live on less than a dollar a day.

“I like to talk to the common people, I don’t like politics,” Azango tells FORBES WOMAN AFRICA. “Why? Because I feel politics come and go.”

But she is committed to journalism that delivers political change. Her reporting attracted so much international attention that the government called for an end to female genital mutilation, although Azango says it continues. Azango’s report on the alleged rape of a 13-year-old girl by a police officer who walked free for over three months, led to the his arrest.

While the horrific violence perpetrated against women during Liberia’s civil war has come to an end, many Liberian women and girls continue to struggle with sexism and abuse and it doesn’t stop in the workplace. One renowned journalist and editor, who died recently, even had a policy of not hiring female reporters.

Wade Williams, 31, is one of two female newsroom chiefs in Liberia, also a New Narratives fellow and Azango’s colleague and friend. Her past three years at FrontPage Africa have proved challenging, with some of her male colleagues hesitant to accept her leading role. But after three years in the job, the reporters have grown to respect her and women have taken a leading role in the newspaper headed by journalist and editor Rodney Sieh.

Last year Williams became the second Liberian woman to win Journalist of the Year at the PUL awards, since the press union was established in 1964.

For Clarke, these achievements have led to a major shift in how female journalists are perceived in Liberia.

“The sheer fact that women, who were once considered worthy of being nothing more than anchors and doing entertainment, are now breaking the most important stories in Liberia and are among the most credible journalists in Liberia has revolutionized everything,” Clarke tells FORBES WOMAN AFRICA.

Back in Azango’s room we discuss the future of her career. She is uncertain as to whether she wants to continue being a journalist or become an activist working with abused women. The line between activism and journalism has always been a thin one for Azango.

As we leave her house she stands on the stoop and yells, “thank you for taking up my whole day,” in a sarcastic tone, pretending not to have enjoyed telling her story. Dressed in leggings, a bright red t-shirt and floral hair tie, Azango is surrounded by children and women with white knuckles rubbing wet clothes against washing racks. She flashes her broad smile and flips out a nonchalant wave. Perhaps she has reason to bluff.