WEIJA, Accra – For close to a year, Evans Antwi had been feeling unwell. His breathing was labored, and he couldn’t sleep. He often felt a tightening in his chest, and he suffered persistent headaches.

Unsure what was happening to him, Evans managed his symptoms with over-the-counter medication. That was until he started coughing out blood. The terrified 33-year-old realised it was time to seek urgent medical help.

“I suddenly started feeling dizzy and reached out for my phone to call my neighbour to accompany me to the hospital,” he says.

Doctors told Evans he was suffering from severe upper respiratory tract infection. They warned that the untreated infection could lead to respiratory failure, which happens when there is too much carbon dioxide in the blood. It can also spread to other parts of the body, including the brain or the heart.

Evans took the doctors’ advice and has since recovered. But he fears his woes are far from over. He lives in Weija, near Accra, with his home located very close to the Empire Cement factory that spews toxins into the air and groundwater.

Evans’ doctors suspect he contracted the infection after prolonged exposure to harmful dust particles and chemicals released into the atmosphere by the factory. He is worried that he will have to battle another infection in the near future.

He is not alone.

Residents across the country who have found themselves living near poorly regulated industrial areas are struggling with the health impacts. In Weija, residents have been living in fear for years, since plans to open the factory were brought to their attention in 2020.

Mr Eddie Quaynor, Chairman of the McCarthy Residents Association, confirmed the fear of residents, stressing it is the main reason why the matter is before the High Court. He says all efforts to have the local and national government to regulate emissions from the factory have failed.

“Our complaints were not resolved or taken seriously by anybody,” Mr Quaynor says.“ The Assembly didn’t do anything about it. They didn’t take notice of [anything] we told them.”

Mr Hope Agboado, the lawyer representing the McCarthy Residents Association confirmed that the case was filed in 2021 and is currently at the oral arguments stage. He says he is hopeful for a fair hearing and is committed to pursuing the case to ensure that the residents’ concerns are addressed.

The Chronicle reached out to Empire Cement, but they declined comment. We also contacted the District Assembly and the Environmental Protection Agency for responses to the community’s accusations. Neither returned emails, text messages or calls.

In the meantime, the factory is producing cement at a brisk pace and with it, toxic fumes that residents blame for a range of illnesses.

Another resident of the area, a Pensioner, who does not want to be named, says he’s unable to leave his room and sit outside because of the plumes of dust from the factory.

“There have been times when the wind shifts towards our side and we find ourselves covered in these white particles,” he says.

“It is like a silent invasion, a constant reminder of the pollution that surrounds us. Sometimes we see dust particles in the air. We are frustrated because the [district] assembly has turned deaf ears to our plight and we hope the court will take a good decision on this matter.”

Joseph Manu, who works at a business centre located close to the factory, complains about occasional breathlessness and fears it could get worse. He has decided to quit his job and move out of the community to a safer area.

“I will leave because I do not feel safe here,” Joseph says.

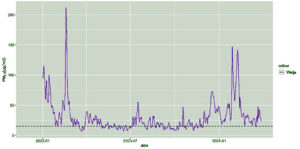

Clean Air One Atmosphere, a Ghanaian NGO, conducted a study between January 2023 and March 2024 using modeled data and found high concentrations of harmful pollutants in the air at Weija. Dr Collins Gameli Hodoli, the lead researcher, says the pollution exceeded the World Health Organisation’s air quality guidelines by an average of 76 percent.

The study focused on the most harmful pollutant, known as particulate matter 2.5 (fine particles with size < 2.5 micron). These can go beyond the respiratory system and lungs to enter the bloodstream, causing heart disease, stroke, infertility, cancer and exacerbating diabetes.

Dr Collins Gameli Hodoli says the research findings suggest emissions from the cement factory could be contributing to the poor air quality by emitting other harmful pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide. This is particularly concerning given the existing sources of air pollution in the area—vehicular emissions and improper waste management such as burning of refuse, a common practice in Ghana.

“We conducted this study because of the [volume] of complaints we have heard from the residents and also the detrimental impact the factory is likely to have on their health,” Dr Collins Gameli Hodoli says.

Dr Emmanuel Duah, a Medical practitioner, explains that the toxic and irritating nature of the pollutants can lead to severe damage to the respiratory system. In some cases, he says, residents risk contracting diseases, including lung dysfunction, cardiovascular diseases and chronic bronchitis.

Dr Duah says that the immediate health effects of inhaling such pollutants can include respiratory allergies and other respiratory symptoms, and long-term exposure can lead to chronic conditions.

“Emissions from these industrial activities have significant health implications. Nitrogen dioxide, for instance, can lead to visual impairment and respiratory diseases like asthma, especially in children,” says Dr Duah.

“Sulphur dioxide can cause breathing difficulties. Carbon monoxide exposure can result in an oxygen imbalance in the body, leading to collapse and in severe cases, death.”

The Medical practitioner says it is very important to recognise the link between industrial air pollution and these serious health conditions, urging authorities to take action to mitigate the risks and ensure the well-being of residents in areas where factories have been built.

This problem extends beyond Weija. Industrial activities in other parts of the country including Tema, Keta and Asokwa in Kumasi are among those that have also been identified by researchers as significant contributors to environmental pollution and health problems among residents and workers. In those cases too, residents have complained that local government and factory owners have failed to monitor emissions and they say they fear retaliation if they complain.

A recent report by the Environment Protection Agency on Accra’s air quality found concerning levels, according to experts. Accra’s air pollution exceeds the WHO annual air quality guideline value by 63.1 percent. In response, the EPA recommended Accra residents take urgent measures, including wearing masks, avoiding outdoor activities, reducing energy use, and using public transport.

Dr Gameli Hodoli and other experts say there is a need for follow-up studies and health monitoring for individuals living in close proximity to industrial areas. He also called on the Environmental Protection Agency to maintain routine air quality monitoring and make this data openly accessible through platforms like dashboards or mobile phone applications, so that residents can take action when air pollution is bad. He is also advocating for the relocation of manufacturing industries like cement plants, away from residential areas.

As part of efforts to address the issue of air pollution in the country, Clean Air One Atmosphere has urgently called for a legal instrument, “Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment/Clean Air Bill” for Ghana.

Experts say major government action is essential if people like Evans are to stop falling sick and dying from the air they breathe.

***

This story is a collaboration between The Chronicle and New Narratives. Funding was provided by the Clean Air Fund. The funder had no say in the story’s content.