Alex Weah had no clue that the sea would swallow up his home when he built his six bedroom house here.

But the Community Youth Chairman and senior student at the United Methodist University watched helplessly in 2017 as the sea quickly overtook the house.

“The sea was coming closer but we were thinking that it was not serious. But in less than two to three months the sea wiped away the entire house,” he recalled on a recent visit to the site with reporters. “Other houses that were in front of us – we had about 200 to 300 houses – which, of course, were wiped away.”

Mr. Weah said he had to send his children to live with his mother and he has been forced to rent a single room in a house with other people.

“I am totally distressed and very unhappy about the situation,” Mr. Weah says.

Over a decade, rising sea levels caused by climate-change, have devastated the lives of many people in Liberia’s nine coastal counties, where 60 percent of the population lives. 800 homes have been swallowed by the sea in West Point alone with 6,500 people forced to find new homes. Major infrastructure such as JFK Hospital, D. Tweh High School and the Hotel Africa are at risk.

Things are set to get a lot worse. Sea levels rise as polar ice caps melt because of rising temperatures. So-called “greenhouse gases” pumped into the atmosphere (mostly by industries countries) trap heat and cause the temperature to rise. A 1.5 celcius rise is already assured. The worry now is that it will go to 2 or even 3 degrees.

An expected sea level rise of just 16cm by 2030 will put 675,000 people at risk in Greater Monrovia according to the World Bank’s 2021 Climate Risk assessment. Coastal towns such as Buchanan, Greenville, Harper and Robertsport face inundation.

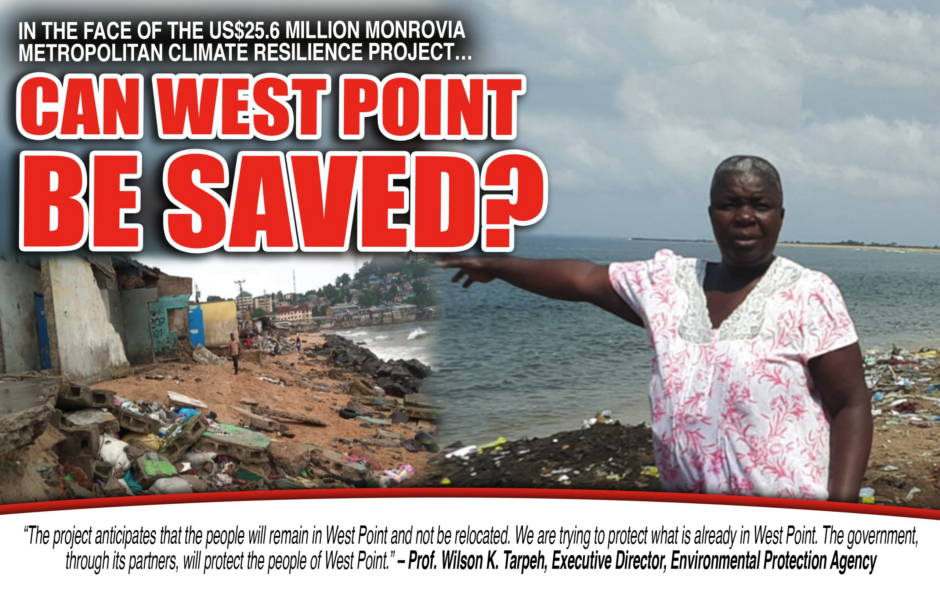

Munah Wleh has not yet lost her home but it could happen any day. The 55-year-old, single mother of four children and six grandchildren, lives in a West Point home that sits perilously close to the sea.

Madam Wleh finds it hard to sleep at night because of the stress. ‘Will this be the night that the sea comes?’ she asks herself.

Sea level rise has dramatically changed West Point since she arrived here as an 8-year-old girl.

“The sea was all the way at the back,” she told reporters, pointing a distance out into the water. “If I tell you the number of houses that were standing here and are now in this sea, you will say I am lying. We had a big school building, A football field, stores and churches here, but the sea has swallowed up all.”

For the people of West Point a remedy is coming. In January the $25.6 million Monrovia Metropolitan Climate Resilience Project kicked off. The project, implemented with the United Nations Development Project, will see large rocks placed along the shoreline to build a wall that will hold the sea back. The project was planned with the world’s best engineers according to UNDP Resident Representative Stephen Rodrigues, and will hold the sea back at least 40 years.

The six year project will take US$17.2 million from the Green Climate Fund, an international fund made up of donations from rich countries to help low income countries adapt to climate change. Another $6.8 million will come from the Liberian government and $US1.5 million from the UNDP.

There will also be a strong livelihood replacement program, according to West Point Commissioner Mr. William C. Wea. Fisherfolk will be trained in other skills and there will be help to move into businesses like fish drying and storage to, “help people move away from the perilous sea.”

The livelihood component will be critical for people here. A Sirleaf administration effort to relocate people from West Point to the Brewerville community, on the outskirts of Monrovia, failed when people were unable to provide for themselves.

The goal of this project is to help people stay, according to Prof Wilson Tarpeh, Executive Director of the Environmental Protection Agency.

“The project anticipates that the people will remain in West Point and not be relocated. We are trying to protect what is already in West Point. The government, through its partners, will protect the people of West Point,” said Prof Tarpeh in an interview.

This is important to the people here.

“We are scared of the sea, but where will we go?” Madame Wleh said. “This is my hustle ground, because fish business is what we can do to support our children in school. So if the government take us to a different place, I, Munah, will not be satisfied because my hustle that I am doing will stop and I will not be able to support my family again.”

“There are many people who are living by fishing in West Point, while for others, it is an easy access to Central Monrovia,” said Commissioner Wea. “So any attempt to relocate people from here to carry them to Brewerville or any other place, it will be like you are taking their breath away.”

The earlier $2m phase of the project in 2018, saw a seawall constructed in New Kru Town, home to an estimated 20,000 inhabitants. The project saved important structures from collapse, including the historic D. Tweh High School and some residential buildings. Similar projects have already been done in Buchanan and will extend to Sinoe County at a later date.

But critics say the project is just putting off the inevitable need to relocate West Point’s residents.

“Any solution of dumping rocks on the beach will be temporary and after a while, when the rocks are covered by sand, the erosion will continue,” said former Mines Minister Dr. Eugene Shannon. He has argued that the area should be turned into a tourism destination.

“Let’s turn West Point into a touristic center, where we will have people coming from Europe, just like what they do in Gambia. Gambia, has thousands of people coming in every summer for tourism.”

The UNDP’s Representative Rodrigues concedes that the coastal defence project is a temporary solution that will give government and residents 40 years to find another one. But he warned the only long term solution is to stop the global warming that is causing sea levels to rise. That will take more than heavy rocks.

“It will take you and me and all people the world over coming together to stop climate change,” said Mr. Rodrigues. “We’re all in this together.”

This story was a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the Climate Change and Land Rights Reporting Project. Funding was provided by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and the American Jewish World Service. The funders had no say in the story’s content.