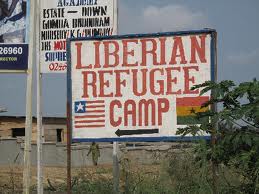

Perched on vast acres of land dotted with concrete buildings marked in colorful chalk, Buduburam Refugee Camp on the outskirts of Accra, Ghana, has always been a place of transit for Liberians. Camp dwellers are like expectant passengers on a flight whose destination is still undetermined. Most of them hope to land in America, or somewhere in Europe, on a resettlement package. They hope to be anywhere but here.

Perched on vast acres of land dotted with concrete buildings marked in colorful chalk, Buduburam Refugee Camp on the outskirts of Accra, Ghana, has always been a place of transit for Liberians. Camp dwellers are like expectant passengers on a flight whose destination is still undetermined. Most of them hope to land in America, or somewhere in Europe, on a resettlement package. They hope to be anywhere but here.

I remember making the two-hour journey in 2002 to the Camp every Friday at the crack of dawn to teach English at the elementary school. Back then, I was a 20-year-old study abroad student at the University of Ghana-Legon, an idealist with many causes. Refugees, and particularly Liberian refugees in Ghana, happened to be my latest crusade.

When I enter the Camp in May for the first time in nearly 10 years, Buduburam looks like a town hit by the plague. It is virtually empty. In 2002, there were over 30,000 refugees at Buduburam. Now about 5,000 remain. Nearly 19,000 refugees have been repatriated to Liberia since October 2004, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Ghana. Just 118 Liberians were resettled to third-party countries from 2007 to 2010.

June 30, 2012 is D-Day for refugees at Buduburam and the thousands of Liberians like them throughout the sub-region and the diaspora, accept those exempt for compelling reasons. On that day, Liberian refugees will be stripped of the protection of refugee status. Liberians who do not have refugee status, but benefit from Temporary Protected Status (TPS) or Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) in the United States are still awaiting their verdict.] The international community now has faith that Liberia has stabilized. UNHCR-Ghana says the country has shown significant improvements in human rights, the rule of law, and procedural democracy through two post-war ‘free and fair’ elections.

I wonder, though, if the international benchmarks for success mean anything to someone who hasn’t touched Liberian soil in over 10 years. I wonder if the international community consulted Liberians before deciding their refugee status would be discontinued. I wonder if the international community knows that although the guns have silenced in Liberia, the war on poverty has only just begun.

In her article, “Humanitarianism in a Straightjacket,” Dr. Barbara Harrell-Bond rages against international agencies such as the UNHCR for not allowing communities they serve to help plan and implement programs that are meant to transform their lives. She is the founder of refugee studies as an academic discipline, and a staunch advocate for refugees. I conducted research with her in Cairo, Egypt, in 2005, and grew to admire her political views. Unlike conventional wisdom that frames refugees as helpless, Harrell-Bond believes they are agents of their own destiny, and should be treated as such.

Indeed, Liberian refugees at Buduburam are far from victims, despite their shared tragedies.

Showing me her dark, airless room deep inside Buduburam, Mercy Sio, 52, keeps a healthy dose of optimism. With tight Bantu knots twisted closely to her scalp, Sio wears a smile that hovers between complacency and faith. Like many refugees here, Sio came to Ghana trying to escape death on Valentine’s Day in 2001. But death followed her instead. Since then she has lost two adult children, a son in Liberia to tuberculosis, and a daughter in Ghana to liver failure.

When Sio first came to Buduburam, UNHCR provided food to the refugees every two to three months. Eventually, the rations tapered off to nothing. She sustained herself on remittances sent by Liberians abroad or by cooking Liberian food in restaurants in Accra. Sio will be returning to Liberia this month with very little to show for her eleven years at Buduburam. She complains that the 30 kilos of luggage UNHCR-Ghana has promised is grossly insufficient. Even with a cash allowance provided by UNHCR-Ghana of US$375 per adult, I wonder how one can pack over a decade of life into a single checked-in bag. I can barely stuff nine months of existence in London into two large-size suitcases for my pending fieldwork to Monrovia.

Some Liberians at Buduburam are more vocal about their anger and disappointment, like Alfred Mawolo Jallah, who is seated by himself under a tree sulking when I enter the Camp. Since 2006, he has served as the Chairman of the Joint Liberian Refugee Committees in Ghana, an organization that advocates on behalf of Liberian refugees at Buduburam. “Our coming here has not helped,” Jallah says.

He accuses UNHCR-Ghana of shirking its responsibilities to the refugees. He says that while the UN agency was responsible for providing basic amenities, Liberians at Buduburam were building their own schools and makeshift houses. The international community’s decision to cease all assistance to Liberians means that the “refugees will be a liability on the Liberian government,” says Jallah. “They are going home the same way they came.” According to Jallah, two thirds of the refugees have no formal education.

To date, the Government of Ghana has not devised a policy to integrate Liberians in Ghana, says UNHCR-Ghana. I believe pressure needs to come from the Liberian government to hold Ghana’s feet to the fire. Given the number of Ghanaians who live and work with ease in Liberia, the least their government could do is allow Liberians the same level of access.

Prospects for more engagement look bleak, however, with accusations being hurled at the Liberian government for not fulfilling its end of the bargain. But the Liberia Refugee Repatriation and Resettlement Commission has attempted to respond to the needs of Liberians returning home by facilitating employment, providing scholarships for vocational and technical education, and enabling refugees to use their skills in agriculture and animal husbandry.

Jallah will return with his family to Liberia this month, and he intends to challenge the government he says has always sided with Ghana at the expense of the refugees. Whether or not these interactions yield positive results, Buduburam will forever be remembered as “Little Liberia,” the transit point that, as of June 30, 2012, ceased to exist.

Born in Monrovia, Liberia, Robtel Neajai Pailey is an opinion fellow with New Narratives, a project supporting leading independent media in Africa. She is currently pursuing a doctorate in Development Studies at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), as a Mo Ibrahim Foundation Ph.D. Scholar. She can be reached at [email protected]