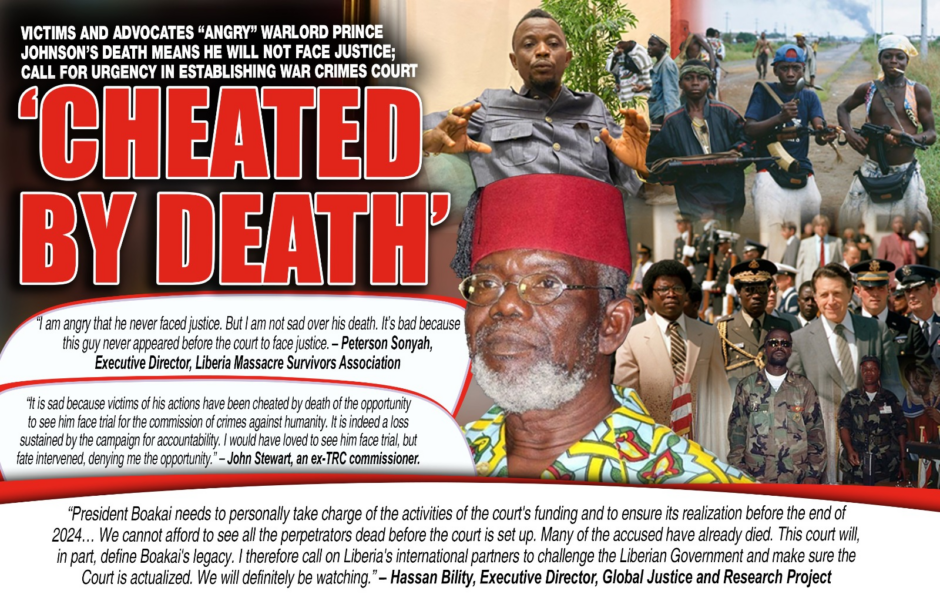

Human rights advocates and victims’ groups are angry over the death of Prince Johnson, the accused notorious warlord, who died suddenly in Paynesville early Thursday morning. Senator Johnson, 72, had high blood pressure, according to his family.

Johnson was seen by many experts as one of the most likely to face prosecution for his many atrocities when he headed the Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia (INPFL), a break away from Charles Taylor’s NPFL. He was named number one on the list of 116 “most notorious perpetrators”, recommended for prosecution by Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He was also the long-time senator for Nimba County, elected to the office three times.

Twenty-one years since the end of the conflict, Liberia’s president and Legislature have finally begun setting up a court to try those accused of the most egregious human rights violations that left 250,000 people dead and millions displaced. Victims will now be robbed of the chance to see the man accused of committing the most atrocities during the conflict tried.

“I am angry that he never faced justice,” said Mr. Peterson Sonyah, executive director of the Liberia Massacre Survivors Association, the largest victims’ and survivors group in Liberia. “I am not sad over his death. It’s bad because this guy never appeared before the court to face justice.”

“It is sad because victims of his actions have been cheated by death of the opportunity to see him face trial for the commission of crimes against humanity,” said Mr. John Stewart, an ex-TRC commissioner, by text message. “It is indeed a loss sustained by the campaign for accountability. I would have loved to see him face trial, but fate intervened, denying me the opportunity.”

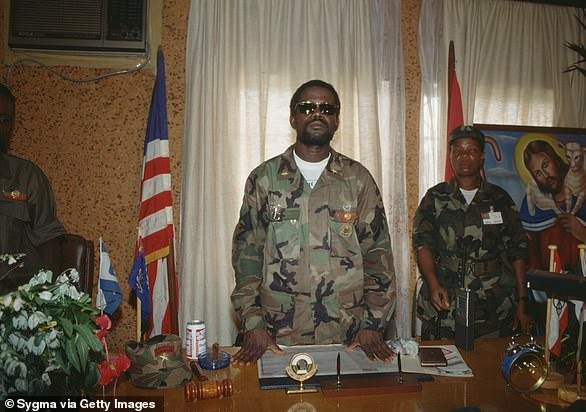

Prince Johnson at slain President Samuel Doe’s desk in 1990

Senator Johnson’s INPFL was accused of committing 2,588 or 2 percent of all crimes reported to the TRC. He was personally accused of committing widespread human rights violations, including “killing, extortion, massacre, destruction of property, force recruitment, assault, abduction, torture & forced labor, rape.”

He always claimed he was acting on behalf of citizens of his home county Nimba, which felt targeted by President Samuel Doe, and challenged the credibility of the TRC report, including in a 2021 interview with the Voice of America. “Why will they refer to a senator like me as a notorious war criminal?” asked Senator Johnson.

While he claimed to support a war crimes court as a chance to clear his name, he repeatedly challenged its legality.

“The people who are clamoring for the economic and war crimes court, it’s not a bad thing,” said Senator Johnson. “But the thing here, we have legal and constitutional instruments that block people from bringing a war crimes court, because the TRC they are basing on, it has flaws and irregularities that led to division within the file and ranks of the TRC commissioners. If you want to bring war crimes court for whatever reason on the basis of TRC, then it will be questionable. If you want to bring war crimes court on the basis on a new beginning to establish the court, filing information, data, that’s a good thing.”

Child soldiers during the Liberian Civil War. Source: Sutori

Legal scholars have repeatedly said that any trials by a Liberian court would not be based on evidence from the TRC. Each case would have to be built from scratch. There are also no legal limitations to trials, as war crimes and crimes against humanity have no statute of limitation, meaning they can be conducted regardless of how long it has been since the alleged crimes were committed.

Several of Senator Johnson’s most notable atrocities claimed the world’s attention, including the torture of Samuel Doe, then-Liberian president, who his troops had captured and tortured. The acts were captured in a video that is available online. President Doe died a day later but it is not clear how. Mr. Johnson repeatedly justified Mr. Doe’s death in interviews and speeches, insisting that Mr. Doe was killed in retaliation for the deaths of “my people,” referring to the people of Nimba County, who revered him as a “political godfather” and “a liberator.”

They elected him senator for 27 years. But he served them for more than 18 years—one of the longest elected officials in Liberia’s post-war history.

President Doe with then Secretary of Defense of the United States Caspar W. Weinberger outside the Pentagon in 1982

Mr. Doe’s murder and that of Linda Drury, a young American woman, haunted the senator. At one-point, American investigators came to Liberia trying to build a case against him for the latter crime. Though he was never charged, his recent years saw his travels restricted. He was put on the US Magnitsky sanctions list in 2021, accused of being “involved in pay-for-play funding with government ministries and organizations for personal enrichment. As part of the scheme, upon receiving funding from the Government of Liberia (GOL), the involved government ministries and organizations launder a portion of the funding for return to the involved participants. The pay-for-play funding scheme involves millions of U.S. dollars. Johnson has also offered the sale of votes in multiple Liberian elections in exchange for money.”

That prevented him from traveling to most Western countries. His travels in Africa were also limited by the risk that he might land in a country where prosecutors might charge him using the principle of universal jurisdiction – meaning he could be tried anywhere, regardless of where the crimes were committed. In an apparent response to the US sanctions, Senator Johnson resigned from his role as third deputy speaker of the regional parliament of the Economic Community of West African States in 2022.

Mr. Johnson’s passing may help Liberia’s push for a war and economics crimes court in two ways: He was the loudest opponent to a court, threatening on occasions to raise a militia should he be indicted. He was also expected to lobby other senators and representatives to block passage of a bill to establish the court, which is expected to come to the Legislature in coming months.

“Yes. It will be an easy one,” said Sumo Kollie Mulbah in a phone interview. He’s the Montserrado County representative who put this year’s resolution to establish a court on the floor of the House. “It will be a very easy one, because Prince Johnson was used as the icon of Nimba County. People felt that the war crimes court is about Nimbaians. No. The issue is about justice for those that died during the war, because we feel that the dead cannot speak for themselves. It’s the living who speaks for the dead and because of that, we must speak for our people that died.”

Sumo Mulbah put the resolution for war and economic crimes courts on the floor of the House. He says Senator Johnson’s death makes it ”easy” for the courts to be legislated.

Senator Johnson was also seen as the biggest security threat to a court, because of his threats to raise a militia to oppose it. His death may reduce any security threats that might have come about as a result of the courts.

Senator Johnson joins a growing list of accused perpetrators who have died without being prosecuted, including Prof. Alhaji G.V. Kromah, George Dweh, Roosevelt Johnson and Francois Massaquoi among others. The administration of Joseph Boakai, in its tenth month, has taken key steps in setting up the court, including the signing of a joint resolution for the court by the Legislature, setting up an office for the court. A bill still needs to pass the Legislature for the court to get underway. Fearing that more accused warlords could die, experts want the government to now move with speed in legislating the court. Any trials would likely still be at least two years away.

“President Boakai needs to personally take charge of the activities of the court’s funding and to ensure its realization before the end of 2024,” said Mr. Bility by text. Mr. Bility is the director of the Global Justice and Research Project, which has helped gather evidence in 15 cases of accused perpetrators in Liberia’s civil wars for law enforcement officials in Europe and the United States. “We cannot afford to see all the perpetrators dead before the court is set up. Many of the accused have already died. This court will, in part, define Boakai’s legacy. I therefore call on Liberia’s international partners to challenge the Liberian Government and make sure the Court is actualized. We will definitely be watching.”

“If we continue to delay, at the end of the day, that’s how it’s going to be because we have lost several of them…people like Tom Woewiyu…if they continue to go like this, who are we going to prosecute?” asked Mr. Sonyah in a phone interview. Woewiyu died of Covid in the United States while awaiting sentencing after being convicted on 14 counts of immigration fraud for lying about his war-related crimes in his immigration proceedings.

Mr. Stewart echoed his sentiments, urging the government to provide start-up funding for the Office of the courts immediately.

“This underscores the urgent need for the GoL [Government of Liberia] to jumpstart the process of accountability by making an initial but substantial contributions as seed funding to enable the office to establish the court to become functional,” said Mr. Stewart. “This is especially in view of the fact that major perpetrators are dying out and thereby denying Justice to victims.”

After the war, Mr. Johnson became a self-styled evangelist, who occasionally used the pulpit of his personal church to preach forgiveness and hate, throwing jibes at his political opponents. He was a king maker in politics, throwing his support behind the presidential candidate who paid the most money. His support decided victories for all of Liberia’s three post-war presidents: Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, George Weah and Joseph Boakai. Political analysts say his death could change Liberia’s political landscape. He also had unsuccessful presidential runs himself in 2011 and 2017.

“Oh yes! PYJ’s [Prince Yormie Johnson’s] death is going to have impact on Nimba and the country at large politically,” said Mr. Franklin Wesseh, ex-chairman of the Center for the Exchange of Intellectual Opinions, a leading point of intellectual convergence for Liberia’s policymakers, politicians and ordinary citizens. “Nimba might no longer be the determiner of Liberia’s President. PYJ told the people of Nimba which way to go, and the obeyed. They saw him as their savior. I doubt strongly if anyone can fill that vacuum anytime soon. No son or daughter or daughter of Nimba has shown that prospect of being able to wield that authority that PYJ commanded.”

Mr. Boakai, who Senator Johnson supported over Mr. Weah during the 2023 presidential election, described him “as a figure who played a pivotal role in Liberia’s complex historical evolution and contributed to national discourse through his service in the Senate,” according to the Executive Mansion.

“The Government of Liberia will work closely with the Johnson family, the Vice President and the people of Nimba to ensure that Senator Prince Y. Johnson receives a befitting farewell in accordance with national traditions,” said the statement.

In a Facebook post, Mr. Weah, who had a falling out with Mr. Johnson in the lead up to the 2023 election, made no mention of his impact on Liberian politics, but said “Liberia is bereaved; Nimba is bereaved; the Liberian Senate is bereaved,” offering his “heartfelt sympathy to the bereaved family and all those impacted by his passing.”

Constitutionally, the election of Johnson’s replacement must be held within 90 days. But the Senate must formally inform the National Elections Commission about the vacancy within 30 days.

“As for replacing PYJ at the Senate, I predict Madam Edith Gongloe-Weh will succeed him,” said Mr. Wesseh in a WhatsApp message. “But she could face a fierce opposition from Representative Samuel Kogar if he decides to contest for the seat too.

This story is a collaboration with FrontPage Africa as part of the West Africa Justice Reporting Project. Funding was provided by the Swedish embassy in Liberia. The donor had no say in the story’s content.