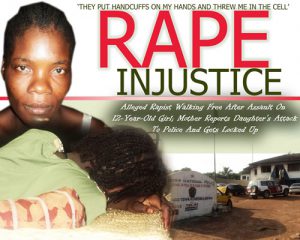

“My daughter is still sick but I send her to sell water also because I don’t have enough money. I want the government to arrest the boy and fight my case because I have nowhere else to go.”

Emma Seekey is 32-year-old single mother who makes a living by selling cold water on the streets to locals.

On June 28, Emma left her daughter washing clothes while she rested at home, until she was told by a neighbor’s child to go to a house close by. When she approached the building, she heard her daughter yelling behind the closed, locked door.

Frantic, Emma and a friend forced the door open, where she saw a young man identified as Joseph Singbeh, believed to be in his 20s, on top of her daughter on a bed.

“I was so angry I jumped on him to fight him, but the neighbors told me to stop and go to the police,” she said.

Emma went to the Zone Three Depot in Congo Town to ask the police for help, and seek justice for her daughter’s rape by asking them to detain the young man.

However, the local police were anything but supportive – according to Emma, the officers in the room taunted her and refused to believe her story.

“One of the officers asked me, ‘Are you sure your daughter didn’t ask the boy to f**k her?’” she said. “I got very angry and asked the police man, ‘Who made that kind of statement?’ and asked if he was also a rapist because he was supporting rape.”

According to Emma, another officer got angry and asked her if she knew to whom she was talking to, and she responded that she didn’t care. The officer then told her to go outside, but she refused, and told him she wasn’t there to talk with him, but to report her daughter’s case inside the station. However, the angered LNP officers refused to let her file a statement – and they decided to detain Emma instead.

‘He Slapped Me’

“He slapped me in the face, and starting pushing me. They put handcuffs on my hands and threw me straight in the cell, and I was in there for three days,” she said. Unfortunately, Emma is one of the many Liberians who has suffered alleged police brutality and whose story rarely ever gets heard in a court case. The Liberian National Police’s (LNP) unresponsiveness and indifference in responding to rape cases contributes to the continuation of these and other crimes.

In addition to dealing with the severity and frequency of rape, Liberians are also faced with police violence and corruption – a widespread occurrence in the country. Although people are encouraged to seek the assistance of their law enforcement whenever there is an injustice, many Liberians who do are met with defiance, carelessness and even brutality. In many cases, this reaction from the LNP prevents people from reporting crimes in the first place; as people feel that the police will not investigate their claims. As a result, many Liberians never see their perpetrators behind bars, and the justice system remains deeply flawed, as President Sirleaf once acknowledged herself.

Examples of this can be recalled in previous events, such as the “Bloody Tuesday” riots in March this year when police brutalized rallying students, who held peaceful demonstrations for the poor teacher’s wages. Over 25 students sustained injuries and were taken to John F. Kennedy Memorial Hospital.

‘No Where Else To Go’

“The police who are supposed to help us when are in trouble are the same police beating us. I have no one else to go to,” says Emma. According to an UNMIL study from the Office of the Gender Advisor in 2007, almost 50 percent of rape victims that year were children under 18, and child rape is reported more frequently than women’s rape. The Ministry of Gender along with the United Nations have done numerous studies on statistics for rape in Liberia, but the data is not precise as it is generally underreported, and the mistreatment of women is the social norm.

When FPA went to the Zone Three Depot to ask the officers for statements based on Emma’s accusations, the reporters first spoke with Officer Amara Kamara, one of the three men Emma identified as her alleged assailant. The officer immediately said, “It is not true. It is false and misleading,” shifted his feet nervously as he spoke, and told the reporters that he is not allowed to speak to the press without the permission of his boss, C.O. Three. Kamara then followed the reporters inside the building to C.O. Three office.

“Police have ethics,” said C.O Three. “And police ethics prevent us from talking to the press. Only George Bardu, the Director of Communications for the LNP, can give us permission to make a statement.”

When contacted over mobile phone by FPA, Mr. Bardu denied permission for the press to speak with C.O Three, Officer Kamara, and R-13 – the three alleged assailants involved in this case.

‘Some Bad Police’

“We acknowledge that there are some bad police officers. This is why we have the Professional Standard Division – to investigate whenever a brutality case comes up,” said Bardu.

However, when FPA went to visit the LNP Headquarters to speak with Mr. Bardu, the reporters were able to read a copy of the LNP ethics and conduct manual in order to investigate whether a strictly enforced rule existed that would prevent police from talking to the press.

According to page 157 in the LNP rulebook under the “Policy for the Dissemination of Public Information to Print and Broadcast Media” section: “LNP Commanders, Supervisors and line officers may, as governed by this policy, provide facts on operational matters within their specific jurisdiction to media representatives. The most senior LNP officer on scene provides these facts or designates a competent and informed LNP officer to brief the media representative.”

LNP Communications Director George Bardu mentioned that while the press may not speak with the officers involved, even though the rulebook mentions the contrary, the victim must report her brutality case to the Professional Standard Division in order for the LNP to look into the accusations. The victim must also file her daughter’s rape case to the Women and Children’s Protection Section at the LNP Headquarters.

‘Daughter Still Sick’

Today, Emma continues to do her best to take care of her daughter and make money. Once Emma was released from her three-day detention, she went back home and took the 12-year-old to a nearby clinic to get her treated for her trauma, spending all the savings of the days she made selling water. At the clinic, the mother obtained confirmation papers from the hospital stating that the young girl had indeed been raped.

The LNP visited Emma’s neighborhood shortly after her release, and took statements from her neighbors to assess the truth of Emma’s story. All of the neighbors attested to the truth of her story, and the LNP said that they would come back to arrest the rapist. However, the LNP never returned again, and the perpetrator continues to roam freely around the neighborhood where Emma and her daughter live.

“My daughter is still sick but I send her to sell water also because I don’t have enough money,” says Emma. “I want the government to arrest the boy and fight my case because I have nowhere else to go.”